Introversion is often misunderstood as shyness, social anxiety, or aloofness. In reality, it's a deeply rooted personality trait shaped by biology, neurochemistry, and evolutionary psychology. Millions of people identify as introverts, preferring solitude, deep conversations, and low-stimulation environments. But what causes someone to be an introvert? The answer lies not in upbringing alone, but in measurable differences in brain function, genetic predisposition, and nervous system sensitivity. Understanding the science behind introversion helps dismantle stereotypes and fosters empathy for those who recharge through quiet reflection rather than social engagement.

The Biological Basis of Introversion

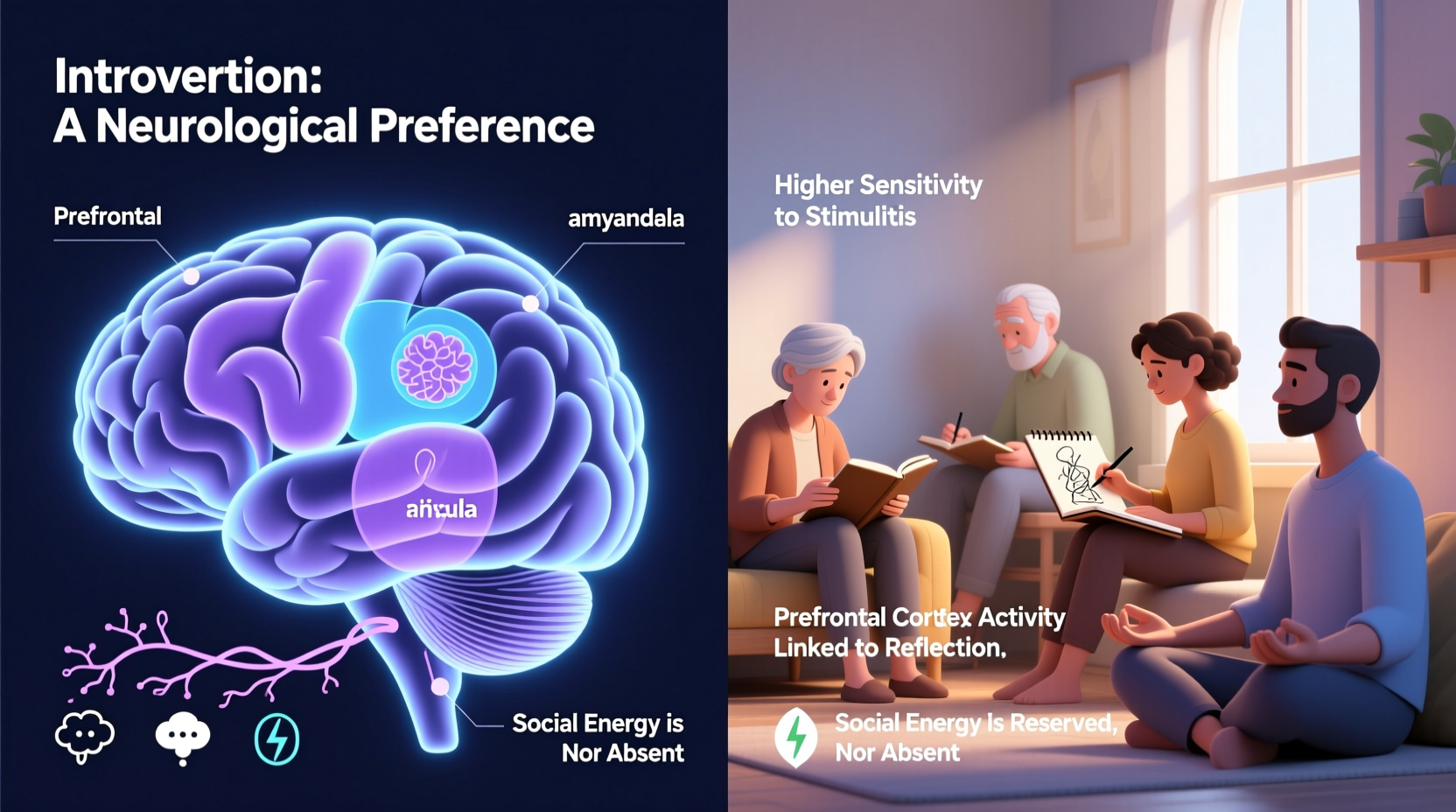

At its core, introversion is linked to how the brain processes external stimuli and rewards. Research in neuroscience shows that introverts and extroverts differ in dopamine sensitivity—the neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and motivation. Extroverts experience a stronger dopamine response to external rewards like social interaction, novelty, and excitement. This makes them seek out stimulation. Introverts, on the other hand, are more sensitive to dopamine and can become overstimulated more easily. As a result, they tend to prefer calm, predictable environments where they can process information internally.

Another key factor is the activity in the prefrontal cortex—the brain region responsible for abstract thinking, decision-making, and self-reflection. Brain imaging studies show that introverts have higher blood flow in this area, indicating more internal processing. This may explain their tendency toward introspection, careful planning, and thoughtful communication.

“Introversion isn’t a flaw—it’s a different neurological wiring that prioritizes depth over breadth in experiences.” — Dr. Marti Laney, author of *The Introvert Advantage*

Genetic and Hereditary Influences

Studies on twins suggest that up to 50% of personality traits, including introversion, are heritable. A child’s temperament—observable as early as infancy—can predict later introversion. Babies who react strongly to new sounds, lights, or faces are more likely to grow into introverted individuals. These “high-reactive” infants display increased amygdala activity, the brain’s emotional alarm center, making them more vigilant and cautious in unfamiliar situations.

This biological sensitivity is not learned behavior. It’s present from birth and influenced by specific gene variants, such as those related to the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR). While serotonin is often associated with mood regulation, certain polymorphisms in this gene correlate with heightened emotional responsiveness and a preference for low-arousal environments—hallmarks of introversion.

Introversion vs. Shyness: Clarifying the Difference

A common misconception is equating introversion with shyness. While both may involve reticence in social settings, they stem from different motivations. Shyness is rooted in fear of judgment or social anxiety—an emotional response driven by insecurity. Introversion, however, is about energy management. Introverts aren’t necessarily afraid of people; they simply gain energy from solitude and lose it in prolonged social interaction.

For example, an introvert might enjoy a small dinner with close friends but feel drained after a crowded networking event—even if they were confident and articulate throughout. In contrast, a shy person might want to engage but feels held back by anxiety. Understanding this distinction is crucial for accurate self-awareness and supportive relationships.

The Role of the Nervous System: High Sensation Seeking vs. Low Threshold

The autonomic nervous system plays a significant role in shaping introverted tendencies. Introverts typically have a lower threshold for sensory input. Bright lights, loud noises, strong smells, or multiple conversations happening at once can quickly lead to cognitive overload. This is due to a more responsive arousal system, meaning their brains register stimulation more intensely.

In contrast, extroverts often have a higher threshold and may actively seek stimulation to reach optimal arousal levels. This difference explains why introverts favor quiet libraries over bustling cafes, and why they may need time alone after social events to \"reset.\"

| Aspect | Introverts | Extroverts |

|---|---|---|

| Dopamine Sensitivity | High – easily overstimulated | Lower – seeks more stimulation |

| Social Energy Source | Recharges through solitude | Gains energy from socializing |

| Preferred Environment | Quiet, low-stimulation | Bustling, high-energy |

| Processing Style | Deep, reflective | Broad, rapid |

| Nervous System Reactivity | High – easily aroused | Low – requires more input |

Real-Life Example: The Workplace Challenge

Sophia, a software developer, consistently delivered high-quality code and insightful feedback during team meetings. However, her manager questioned her leadership potential because she avoided office mingling and rarely spoke up in large group settings. After taking a personality assessment and discussing her needs, Sophia explained that open-plan offices and back-to-back meetings left her mentally exhausted. With accommodations—like designated focus hours and remote work options—her productivity soared. Her story highlights how workplaces often undervalue introverted strengths: deep concentration, strategic thinking, and listening skills.

When environments honor natural temperament, introverts thrive without needing to perform extroversion—a practice that leads to burnout over time.

Actionable Tips for Introverts and Those Who Support Them

- Respect downtime—solitude is not rejection, but restoration.

- Create low-stimulation spaces at home or work for focused thinking.

- Prepare for social events in advance to manage energy effectively.

- Communicate boundaries kindly but clearly (“I’ll join the first hour of the party”).

- Advocate for flexible work arrangements that support deep work.

Checklist: Supporting an Introverted Colleague or Loved One

- Offer one-on-one interactions instead of large group gatherings when possible.

- Give them time to respond—don’t rush their answers in conversations.

- Recognize contributions made in writing or smaller settings, not just public forums.

- Avoid labeling them as “quiet” or “aloof” without understanding their energy needs.

- Encourage autonomy and provide space for independent work.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can someone be both introverted and socially skilled?

Absolutely. Social skill is learned behavior; introversion is innate temperament. Many introverts are excellent communicators, empathetic listeners, and effective leaders—they simply prefer meaningful interactions over frequent ones.

Is introversion becoming less accepted in modern culture?

In many ways, yes. Western societies often reward extroverted traits—charisma, assertiveness, visibility—especially in education and corporate environments. However, growing awareness of neurodiversity and psychological well-being is shifting attitudes toward greater acceptance of introverted strengths.

Can introversion change over time?

While core temperament remains stable, people can develop coping strategies and adapt behaviors. An introvert may learn to navigate social demands effectively, but their underlying need for solitude and reflection usually persists. Growth isn't about becoming extroverted—it's about thriving as your authentic self.

Conclusion: Embracing Neurological Diversity

Introversion is not a deficiency to correct, but a variation in human design with distinct advantages. From enhanced creativity to superior problem-solving under pressure, introverts contribute depth and resilience to teams, relationships, and communities. By understanding the science—genetics, brain chemistry, and nervous system function—we move beyond stereotypes and create spaces where all temperaments can flourish.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?