Muteness—defined as the inability or unwillingness to speak—is not a single condition but a symptom that can stem from a wide range of physical, neurological, developmental, and psychological factors. While some individuals are mute due to structural impairments in speech production, others may choose not to speak due to trauma, anxiety, or neurodivergence. Understanding the root causes is essential for proper diagnosis, support, and inclusion. This article examines the most common and lesser-known reasons behind muteness, offering clarity for caregivers, educators, and healthcare professionals.

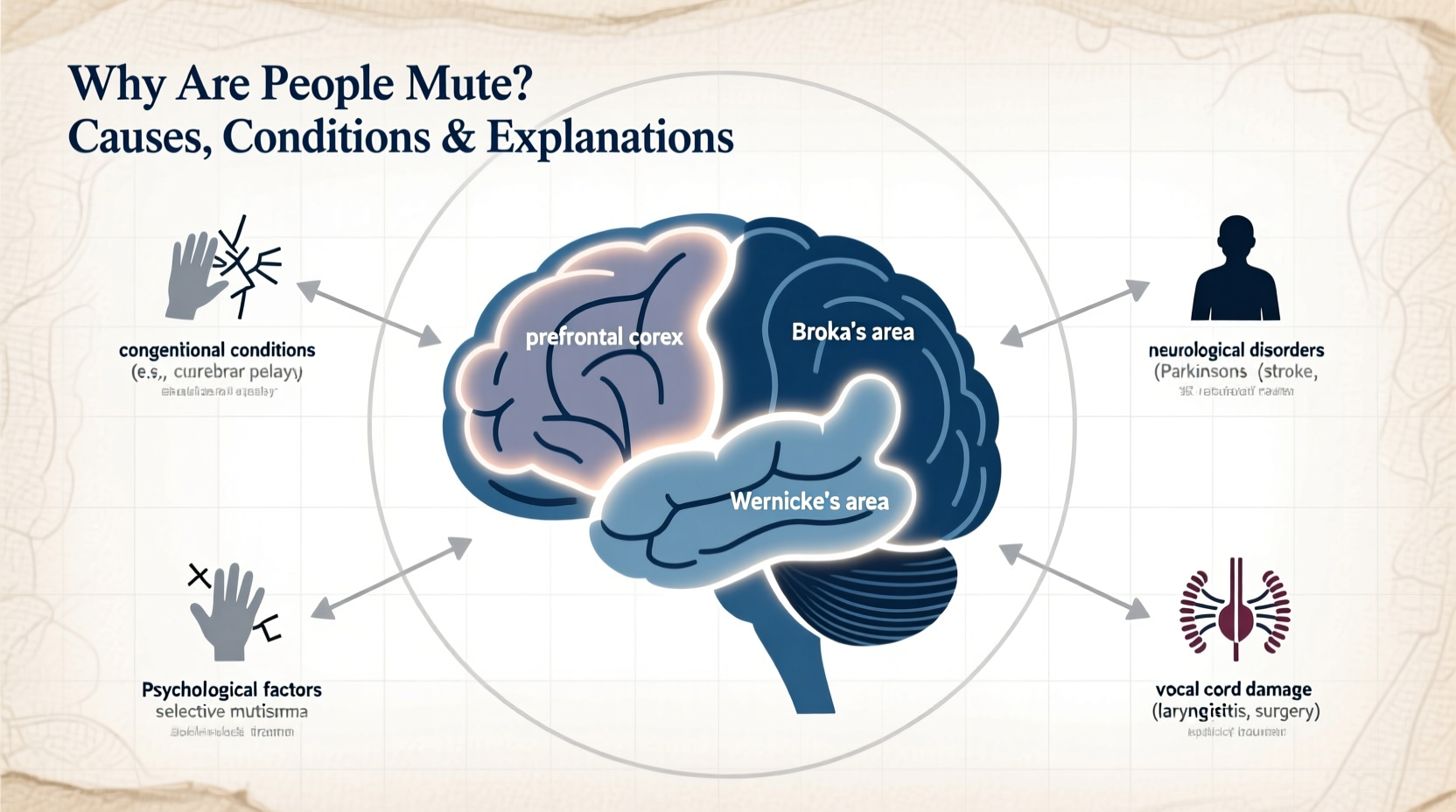

Physical and Neurological Causes of Muteness

Some forms of muteness result from tangible impairments in the body’s ability to produce speech. These are often diagnosed early in life and require medical intervention.

- Congenital abnormalities: Conditions like cleft palate, laryngeal atresia, or underdeveloped vocal cords can prevent normal sound production from birth.

- Neurological disorders: Cerebral palsy, Parkinson’s disease, and stroke can damage brain regions responsible for motor control of speech (Broca’s area), leading to expressive aphasia or anarthria.

- Auditory processing issues: Profound deafness, especially when undiagnosed in early childhood, can prevent language acquisition and spoken communication.

- ALS (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis): Progressive degeneration of motor neurons eventually affects the muscles used for speech.

In these cases, muteness is not a choice but a consequence of physiological limitations. Assistive technologies such as text-to-speech devices or augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) systems become vital tools for expression.

“Speech requires coordination between the brain, nerves, and muscles. When any part of this system fails, verbal communication becomes impossible.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Neurologist and Speech Disorder Specialist

Developmental and Cognitive Conditions

Many children who do not speak by expected developmental milestones are evaluated for underlying cognitive or neurodevelopmental conditions. These are not always permanent, and early intervention can significantly improve outcomes.

| Condition | Description | Potential for Speech Development |

|---|---|---|

| Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | Neurodevelopmental disorder affecting social interaction and communication; some individuals are nonverbal or minimally verbal. | Varies widely; many develop functional speech with therapy. |

| Intellectual Disability | Cognitive limitations that may delay or prevent language acquisition. | Depends on severity; AAC often supports communication. |

| Global Developmental Delay | Delays across multiple domains including speech and motor skills. | Many catch up over time with early intervention. |

| Childhood Apraxia of Speech (CAS) | Motor planning disorder where the brain struggles to coordinate speech movements. | Highly treatable with intensive speech therapy. |

Psychological and Emotional Factors

Not all muteness originates from physical causes. Psychological conditions can lead to selective or reactive mutism, particularly in children and trauma survivors.

Selective Mutism

This anxiety-based disorder typically appears in children between ages 2 and 6. Affected individuals speak freely in safe environments (like home) but remain silent in social settings such as school. It is often mistaken for shyness but is far more severe and persistent.

Trauma-Induced Mutism

Sudden muteness following a traumatic event—such as abuse, violence, or loss—can be a protective mechanism. The brain suppresses speech as part of a dissociative response. This form of muteness is rare but documented in clinical psychology.

Elective Mutism

In some cases, individuals consciously choose not to speak, often as a form of protest, spiritual practice (e.g., monastic silence), or coping strategy. Unlike pathological muteness, this is voluntary and context-dependent.

“Silence after trauma isn’t defiance—it’s often the mind’s way of surviving overwhelming stress.” — Dr. Marcus Reed, Clinical Psychologist

Case Study: A Child’s Journey Through Selective Mutism

Emily, age 5, spoke normally at home but had not uttered a word at preschool for eight months. Teachers assumed she was shy or defiant. After referral to a child psychologist, she was diagnosed with selective mutism. Her parents and teachers implemented a behavioral plan involving gradual exposure, positive reinforcement, and play-based therapy. Within six months, Emily began using single words during circle time. By age 7, she was participating in class discussions. Her case highlights the importance of accurate diagnosis and compassionate, structured support.

Step-by-Step Guide to Supporting a Non-Speaking Individual

Whether the cause is developmental, medical, or psychological, supporting someone who doesn’t speak requires patience and strategy. Follow these steps:

- Rule out medical causes: Schedule evaluations with a pediatrician, ENT, audiologist, or neurologist as needed.

- Assess hearing and cognition: Ensure auditory processing and intellectual capacity are properly evaluated.

- Consult a speech-language pathologist: Begin therapy tailored to the individual’s needs.

- Introduce alternative communication: Use picture boards, sign language, or digital AAC devices.

- Create a low-pressure environment: Avoid forcing speech; instead, model communication and reward attempts.

- Involve mental health professionals if needed: For suspected anxiety, trauma, or selective mutism.

- Educate caregivers and peers: Foster understanding to reduce stigma and isolation.

Common Misconceptions About Muteness

Muteness is often misunderstood. Below are myths that hinder support and inclusion:

- Myth: Non-speaking people lack intelligence.

Truth: Many non-verbal individuals have average or above-average cognitive abilities. - Myth: They don’t want to communicate.

Truth: Most desire connection but use different methods—writing, gestures, or technology. - Myth: All autism-related muteness is permanent.

Truth: Communication skills can develop over time with appropriate support.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a person suddenly become mute?

Yes, sudden muteness can occur due to stroke, brain injury, severe trauma, or acute psychological stress. This is known as acquired mutism and requires immediate medical or psychiatric evaluation.

Is being mute the same as being nonverbal?

While often used interchangeably, “mute” typically refers to the inability to produce speech, whereas “nonverbal” means not using spoken language—but may still include other forms of communication. Not all nonverbal people are mute; some choose not to speak but can if they wish.

Can someone who is mute learn to speak later in life?

In some cases, yes. Children with developmental delays or apraxia often gain speech through therapy. Adults recovering from stroke or trauma may also regain speech with rehabilitation. However, for those with profound neurological or congenital conditions, speech may never develop, making alternative communication essential.

Conclusion: Recognizing Silence as a Form of Communication

Muteness is not absence—it is a signal. Whether rooted in biology, psychology, or environment, it demands attention, not assumptions. Recognizing the diverse causes allows for better diagnosis, more effective interventions, and greater empathy. Families, educators, and healthcare providers must shift from expecting speech to enabling communication in all its forms.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?