The word “pickle” is so commonly used in everyday conversation that few people stop to wonder why a pickled cucumber bears that name — especially since \"pickle\" can technically refer to any preserved food. Yet in countries like the United States and Canada, “pickle” has become nearly synonymous with pickled cucumber. This linguistic shorthand raises an interesting question: how did one specific type of preserved vegetable come to dominate the meaning of an entire category of food? The answer lies in a blend of etymology, colonial history, agricultural availability, and cultural evolution.

The Etymological Roots of “Pickle”

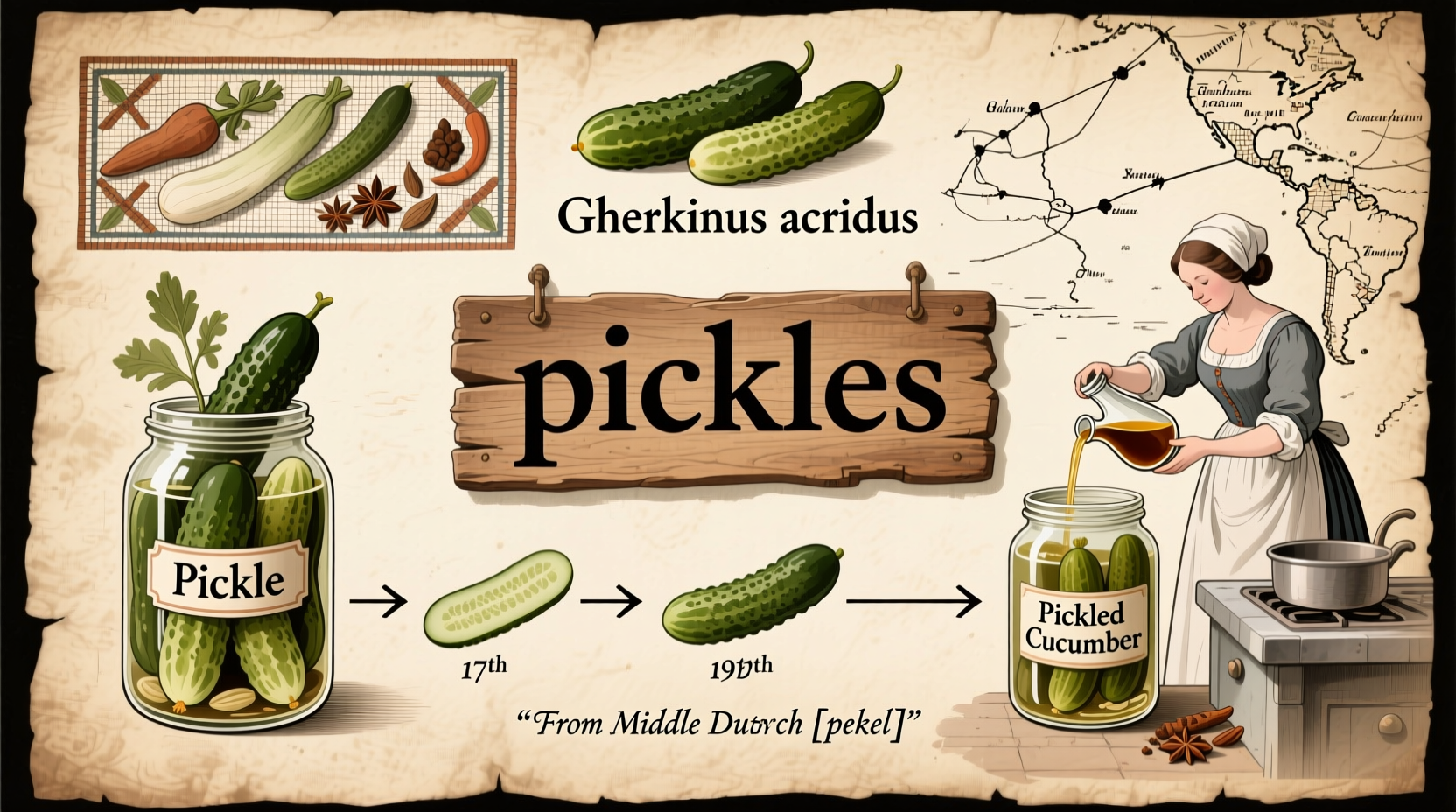

The term “pickle” does not originate from cucumbers at all. Its roots trace back to the Dutch word pekel or the northern French word pique, both referring to brine or salted preservation solutions. In Middle English, the word evolved into “picil” or “pykill,” describing the process of preserving food in vinegar or brine. By the 1500s, “pickle” had entered common usage as a noun for foods preserved through fermentation or acidification.

Originally, “pickle” referred broadly to any preserved item — onions, eggs, peppers, even meats. The verb form meant “to preserve,” and the noun described the resulting product. Over time, however, regional preferences began narrowing the definition. In Britain, for example, “pickle” often refers to a mixed condiment of chopped vegetables in spiced vinegar, while in North America, it became overwhelmingly associated with cucumbers.

“Language evolves alongside diet. When one food dominates a category, its name often absorbs the broader term.” — Dr. Helen Marrow, Historical Linguist, University of Toronto

How Cucumbers Became Synonymous with Pickles

The shift from a general term to a specific reference began in the 17th century, as European settlers brought both cucumbers and pickling traditions to North America. Cucumbers were easy to grow in temperate climates, reproduced quickly, and were ideal for preservation during long winters. As a result, home pickling of cucumbers became widespread.

By the 1800s, commercially produced pickled cucumbers were appearing on grocery shelves. Brands like Heinz began mass-producing “dill pickles” and “bread-and-butter pickles,” further cementing the cucumber’s dominance in public perception. Because cucumbers were the most frequently pickled vegetable in American households, the word “pickle” gradually became shorthand for pickled cucumbers — even though technically, a pickle is any preserved food.

A Cultural Divide: What “Pickle” Means Around the World

The meaning of “pickle” varies significantly by region, highlighting how language adapts to local cuisine. A comparison reveals these key differences:

| Region | Common Meaning of “Pickle” | Typical Ingredients |

|---|---|---|

| United States & Canada | Pickled cucumber (whole or sliced) | Cucumbers, vinegar, dill, garlic |

| United Kingdom | Chopped mixed vegetables in spiced vinegar | Cauliflower, onions, gherkins, peppers |

| India | Spicy, oil-based preserved fruits/vegetables | Mango, lime, chili, mustard oil |

| Germany | Sour gherkins (often fermented) | Kirby cucumbers, brine, dill |

| Japan | Quick-pickled vegetables (tsukemono) | Daikon, cucumber, plum |

This global variation underscores that the American association of “pickle” with cucumbers is culturally specific — not universal. In many places, calling a cucumber a “pickle” would be accurate, but incomplete without context.

From Fermentation to Shelf-Stable Jars: The Evolution of Pickle-Making

The method of pickling has also influenced the terminology. Traditionally, pickles were made through lacto-fermentation — a natural process where beneficial bacteria convert sugars into lactic acid, preserving the cucumber and enhancing flavor. These were known as “half-sour” or “full-sour” pickles, depending on fermentation time.

In the 20th century, vinegar-based pickling became dominant due to its consistency, shorter processing time, and longer shelf life. This industrial shift made pickles more accessible but also standardized their taste and appearance. Supermarkets stocked rows of green, vinegar-soaked cucumbers labeled simply as “pickles,” reinforcing the idea that this was the default form.

Despite this, artisanal and fermented pickles have seen a resurgence in recent years, driven by interest in gut health and traditional foodways. Farmers’ markets and specialty stores now offer naturally fermented varieties that differ sharply in taste and texture from their commercial counterparts.

Step-by-Step: How Traditional Fermented Pickles Are Made

- Select fresh, firm Kirby cucumbers (smaller varieties work best).

- Wash thoroughly and trim blossom ends to prevent softening.

- Prepare a brine of water and non-iodized salt (typically 3–5% salinity).

- Add flavorings: fresh dill, garlic, mustard seeds, and grape leaves (for crispness).

- Pack cucumbers tightly into a clean jar, submerging them completely in brine.

- Cover loosely and store at room temperature for 5–10 days, away from direct sunlight.

- Check daily for bubbles (signs of fermentation) and taste after day 5.

- Once desired sourness is reached, seal and refrigerate to slow fermentation.

Mini Case Study: The Rise of the Kosher Dill

In early 20th-century New York City, Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe brought their tradition of fermenting cucumbers in garlicky brine. Sold from wooden barrels in Lower Manhattan, these “kosher dills” became a staple of delis and street carts. Though not necessarily certified kosher, they followed traditional preparation methods observed in Jewish households.

The popularity of these pickles spread beyond immigrant communities, becoming emblematic of New York flavor. Today, brands like Guss’ Pickles and Rao’s continue the legacy, offering fermented dills that reflect both cultural heritage and regional pride. This case illustrates how a specific community’s food practice can influence national vocabulary — helping solidify the cucumber’s place at the center of the “pickle” identity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are all pickles made from cucumbers?

No. While in North America the word “pickle” usually refers to cucumbers, technically any vegetable, fruit, or even egg preserved in brine or vinegar can be a pickle. Examples include pickled jalapeños, beets, and hard-boiled eggs.

Why do some pickles stay crunchy while others turn soft?

Crispness depends on several factors: using fresh cucumbers, removing blossom ends, adding tannin-rich leaves (like oak or grape), and avoiding excessive heat during processing. Fermented pickles often retain better texture than boiled vinegar pickles.

Is there a difference between a “pickle” and a “gherkin”?

Yes. Gherkins are a specific variety of small cucumber (Cucumis anguria) often used for pickling. In some regions, especially in Europe, “gherkin” refers to any small pickled cucumber, regardless of cultivar.

Final Thoughts and Call to Action

The journey from “pekel” to “pickle” is more than a linguistic curiosity — it reflects how food, culture, and language shape one another. While pickled cucumbers dominate the modern understanding of the word, remembering its broader roots opens up a world of flavor and tradition. From Indian mango achar to Japanese takuan, pickling is a global art form with endless variations.

Next time you reach for a pickle, consider experimenting beyond the cucumber. Try making your own fermented vegetables, explore international pickle styles, or simply read ingredient labels with new awareness. Language may have narrowed the meaning, but your palate doesn’t have to follow suit.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?