It’s a familiar holiday frustration: you hang your favorite string of mini lights, plug it in—and the first 20 bulbs shine brightly, while the last 30 glow faintly, unevenly, or not at all. You check for broken bulbs, swap fuses, even try a different outlet—but the dimming persists. This isn’t faulty manufacturing or aging filaments alone. It’s physics in action: voltage drop. Unlike flickering caused by loose connections or blown shunts, consistent dimming from one end of a string to the other points squarely to a fundamental electrical phenomenon that affects every incandescent and many LED light sets. Understanding voltage drop doesn’t require an engineering degree—but it does require knowing how electricity behaves under load, over distance, and through resistance. This article explains exactly why it happens, how to recognize its signature patterns, and—most importantly—how to solve it before your display loses its sparkle.

What Voltage Drop Really Is (and Why It’s Not Just “Old Wires”)

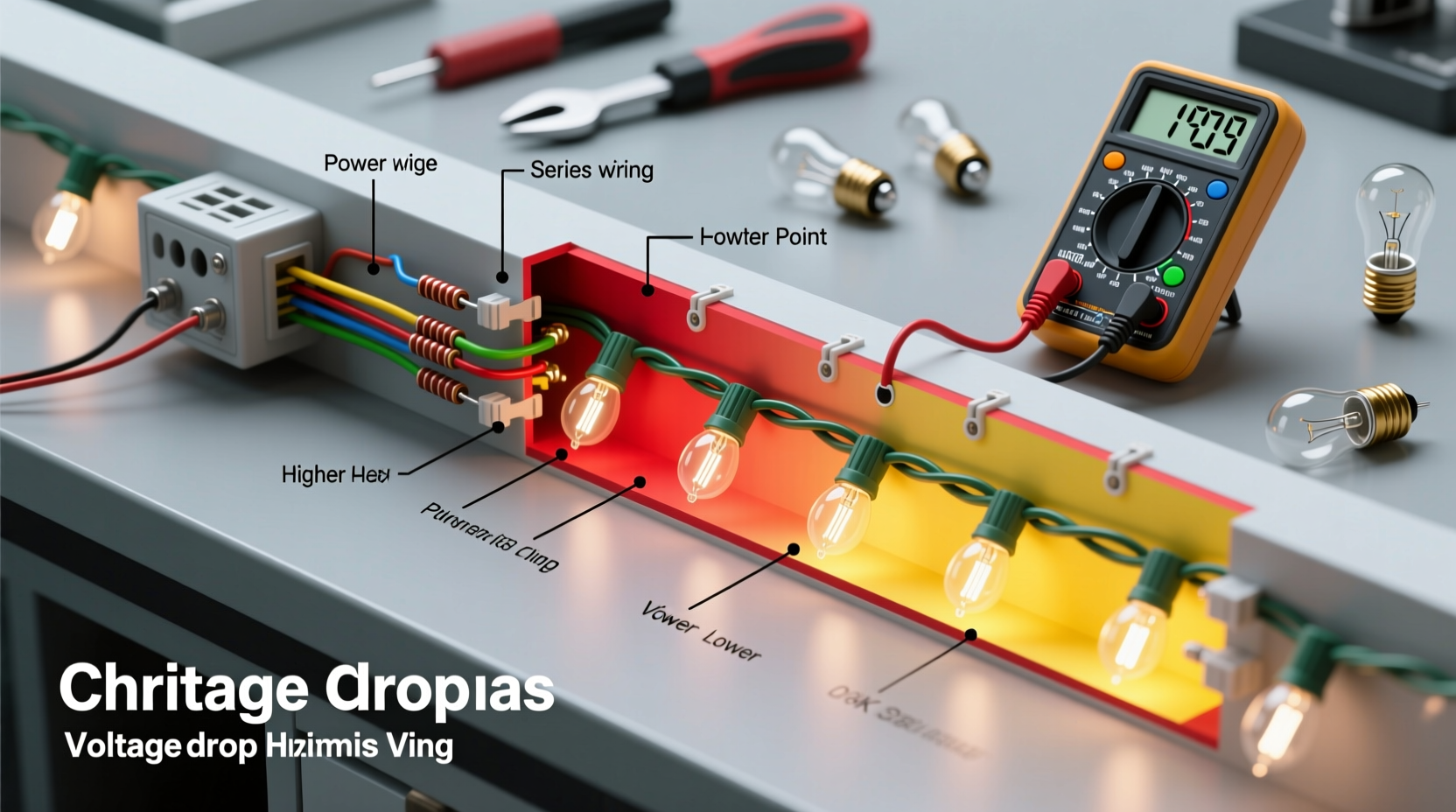

Voltage drop is the reduction in electrical potential (measured in volts) that occurs as current flows through any conductive material with resistance—including the copper wires inside your light string. According to Ohm’s Law (V = I × R), the voltage lost across a wire segment equals the current (I) multiplied by the resistance (R) of that segment. In a typical 100-light incandescent mini-string rated for 120 V, the bulbs are wired in series-parallel configurations—often five bulbs per series sub-circuit, with those sub-circuits connected in parallel. As current travels from the plug end toward the far end, it must pass through progressively more wire length. Each inch adds resistance. While tiny individually, cumulative resistance across 50 feet of thin-gauge wire can cause measurable voltage loss—sometimes 6–12 volts by the final sub-circuit.

This matters because incandescent bulbs are highly sensitive to supply voltage. A 2.5-volt mini-bulb operating at just 2.2 volts will emit roughly 30% less light and appear noticeably dimmer; at 2.0 volts, output drops over 50%. Even modern LED strings—though more efficient—rely on internal constant-current drivers or resistors calibrated for nominal input. Under-voltage forces LEDs to draw less current or triggers undervoltage protection, resulting in reduced brightness or intermittent cutoff.

“Voltage drop isn’t a defect—it’s an inevitable consequence of physics. The real issue arises when designers underestimate wire gauge, string length, or total load, especially in consumer-grade seasonal lighting.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Electrical Engineering Faculty, Purdue University School of Engineering

How to Spot Voltage Drop (vs. Other Common Causes)

Not all dimming is voltage drop. Distinguishing it from other failures prevents wasted troubleshooting time. Voltage drop has three unmistakable hallmarks:

- Directional gradient: Brightness decreases steadily from plug-in end to far end—not randomly or clustered around one bulb.

- Consistency across conditions: Dimming remains identical whether the string is plugged directly into an outlet or through an extension cord (unless that cord is undersized).

- No effect from bulb swapping: Replacing a “dim” bulb with a known-good one doesn’t restore brightness—because the problem lies upstream in the wiring, not the bulb itself.

In contrast, a failed shunt (in incandescent sets) causes complete darkness *after* a dead bulb—not gradual dimming. Loose neutral connections often cause entire sections to blink or go dark intermittently. And poor-quality LED drivers may cause uniform dimming across the whole string—not a gradient.

The 5 Key Contributors to Excessive Voltage Drop

While voltage drop is natural, excessive dimming signals design or usage choices that amplify it. Here are the five most common contributors—ranked by real-world impact:

- String length beyond manufacturer rating: Many 100-light sets are rated for a maximum of 2–3 sets daisy-chained. Going beyond this compounds resistance exponentially—not linearly—because each added set increases both total current draw and total wire length in the path.

- Undersized internal wiring: Budget light strings often use 28–30 AWG wire instead of the more robust 24–26 AWG found in commercial-grade products. Resistance per foot doubles when moving from 26 AWG to 28 AWG.

- Daisy-chaining incompatible sets: Mixing incandescent and LED strings—or connecting newer low-wattage LEDs to older high-load incandescent-rated controllers—creates mismatched current demands and unpredictable voltage distribution.

- Poor-quality or excessively long extension cords: A 100-foot 16 AWG extension cord can add 1.5+ volts of drop *before* current even reaches your first light string. Using 18 AWG makes it worse—especially under load.

- Cold-temperature operation: Copper resistance increases ~0.4% per °C drop. At 20°F (−7°C), resistance is ~5% higher than at 70°F—enough to push marginal strings into visible dimming.

Practical Solutions: From Quick Fixes to Long-Term Upgrades

Fixing voltage drop requires matching the solution to your display’s scale, budget, and technical comfort level. Below is a step-by-step approach proven effective across residential and municipal installations:

Step 1: Measure and Map the Problem

Unplug everything. Use a digital multimeter to record voltage at the first, middle, and last socket of each string while powered. Note ambient temperature. Compare readings to the string’s rated input (e.g., 120 V ±5%). A >8 V drop between first and last socket confirms meaningful voltage loss.

Step 2: Reduce Cumulative Load

Break long daisy chains. If you’re running eight 100-light sets end-to-end, reconfigure into four independent two-set circuits—each powered from its own outlet or a heavy-duty power strip. This cuts the longest single current path in half.

Step 3: Upgrade Feeder Wiring

Replace generic extension cords with 12 AWG or 10 AWG outdoor-rated cords no longer than necessary. For permanent displays, install dedicated 15-amp GFCI-protected outlets closer to light zones—reducing feeder distance to under 25 feet.

Step 4: Choose Voltage-Stable Products

Look for strings explicitly labeled “constant-voltage” or “full-string brightness guaranteed.” These use thicker internal wiring, integrated voltage-regulating ICs (in LEDs), or distributed power injection—where additional power feeds enter mid-string to “recharge” voltage.

Step 5: Add Mid-String Power Injection (Advanced)

For large-scale displays (e.g., roof lines >150 ft), splice a second power cord into the string at the 50% point using waterproof, UL-listed connectors. This effectively creates two shorter circuits—halving voltage drop. Requires basic soldering and heat-shrink insulation but eliminates gradients entirely.

Do’s and Don’ts: Voltage Drop Prevention Checklist

| Action | Do | Don’t |

|---|---|---|

| Extension Cords | Use 12 AWG or heavier, ≤50 ft, rated for outdoor use and continuous load | Use indoor cords, 16 AWG+, or lengths >100 ft |

| Daisy Chaining | Follow manufacturer’s max-connect limit (e.g., “connect up to 3 sets”) | Chain beyond specs—even if they “light up”—to avoid thermal stress and accelerated drop |

| LED Selection | Choose strings with built-in voltage compensation or “true parallel” wiring | Assume all “warm white” LEDs perform identically—voltage sensitivity varies widely by driver design |

| Testing | Test voltage under actual operating conditions (cold, full load) | Rely solely on visual inspection—brightness perception is unreliable below 20% variance |

Real-World Example: The Neighborhood Roofline Rescue

In December 2022, the Henderson family installed 420 feet of premium warm-white LED rope lights along their split-level roofline. They used a single 100-ft 16 AWG extension cord from the garage outlet and daisy-chained six 70-ft segments. The first 100 feet glowed warmly. By the third segment, brightness dropped 40%. By the sixth, LEDs were barely visible after dusk. A neighbor—an electrician—measured 112 V at the start and only 98 V at the end. He recommended three changes: (1) replace the extension with a 50-ft 12 AWG cord, (2) break the chain into three independent 140-ft loops fed from separate outlets, and (3) install a $12 inline voltage booster at the midpoint of the longest loop. Within two hours, brightness was uniform across all segments—verified with a lux meter. Total cost: $48. Total time saved avoiding annual re-hanging: 7 hours.

FAQ: Clearing Up Common Misconceptions

Can I fix voltage drop by adding a higher-voltage transformer?

No—and it’s dangerous. Household light strings are designed for 120 V nominal. Supplying 125 V or more risks overheating wires, degrading insulation, and voiding UL certification. Voltage boosters must be specifically engineered for low-voltage DC LED systems and installed according to manufacturer instructions—not jury-rigged into AC mains.

Why do my new LED lights dim more than my old incandescent ones?

They likely don’t—your perception is skewed. Incandescents dim gradually and predictably as voltage falls. Many budget LEDs use simple resistor-based current limiting. When voltage drops below threshold, they either cut off entirely (causing “black spots”) or shift color temperature, making remaining light appear duller. Higher-end LEDs with switching regulators maintain brightness longer—but cost more.

Will upgrading to “commercial grade” lights always solve it?

Usually—but verify specifications. Some “commercial” labels refer only to weatherproofing or warranty length, not wire gauge or voltage regulation. Check for published data: minimum operating voltage (e.g., “operates down to 108 V”), wire gauge (24 AWG or thicker), and maximum daisy-chain length (e.g., “up to 1,000 ft with power injection”).

Conclusion: Light With Confidence, Not Compromise

Voltage drop isn’t a flaw in your holiday spirit—it’s a solvable engineering challenge. Once you recognize its gradient pattern, understand its roots in wire resistance and current flow, and apply targeted fixes like strategic power distribution and appropriate cabling, your lights will shine evenly, safely, and reliably year after year. You don’t need to sacrifice scale for consistency, nor beauty for technical soundness. The most dazzling displays aren’t the longest or brightest alone—they’re the ones where every bulb performs as intended, from first to last, because the fundamentals were respected. This season, take ten minutes to measure one string, review your daisy-chain count, and swap out that flimsy extension cord. That small act transforms frustration into control—and turns uneven glow into unified brilliance. Your lights—and your neighbors’ admiration—will thank you.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?