Eggshell color has long fascinated home cooks, farmers, and food scientists alike. Walk into any grocery store or farmers market, and you’ll likely see a spectrum of eggshells—creamy whites, soft browns, even pale blues and greens. But why are some eggs white while others are brown or tinted? The answer lies not in nutrition or taste, as many assume, but in the biology of the hen that laid them. Understanding eggshell pigmentation reveals a blend of genetics, breed traits, and natural biochemistry that shapes one of breakfast’s most iconic staples.

The Genetics Behind Eggshell Color

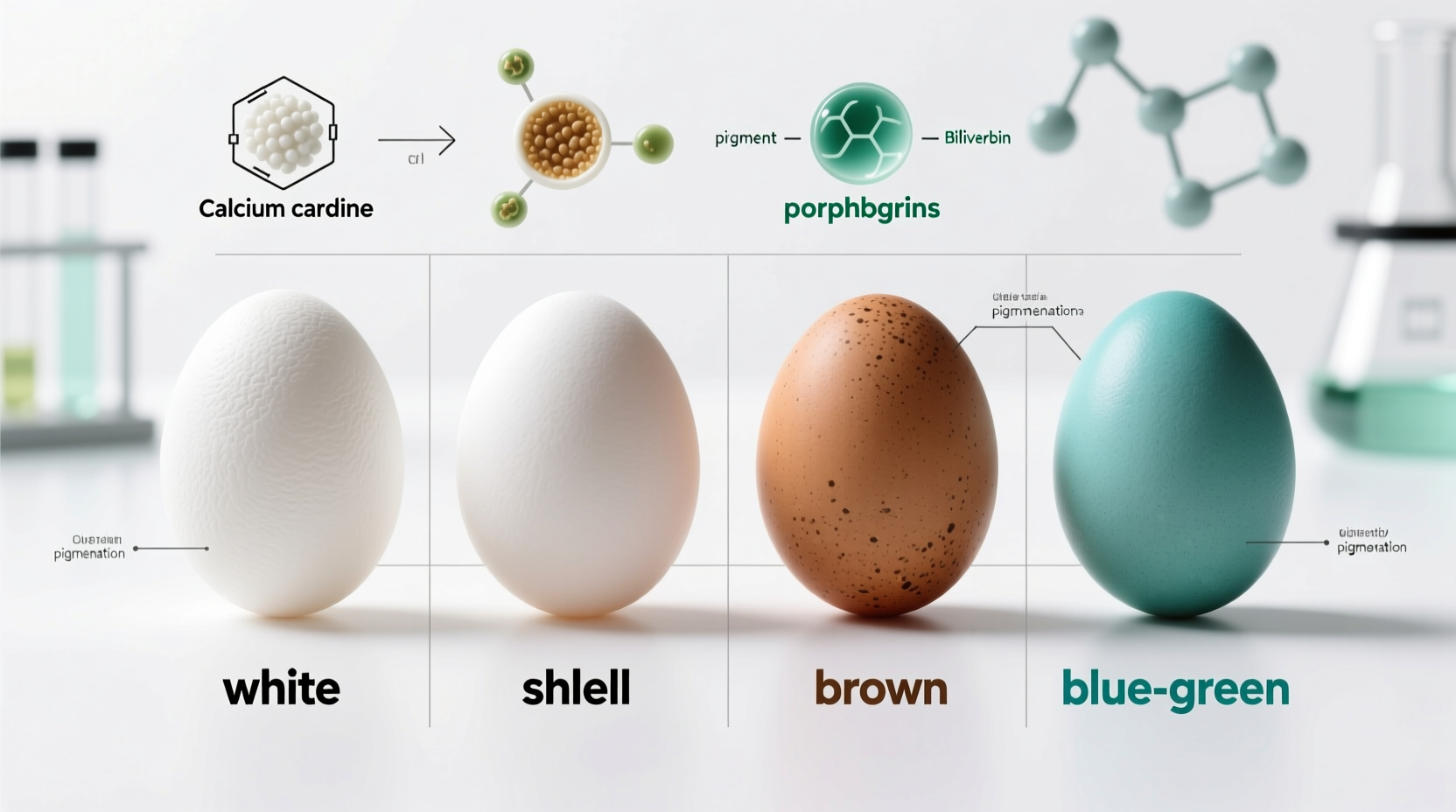

All eggshells start out white. This fact often surprises people who assume brown or colored shells come from different base materials. In reality, the outer layer of pigment is applied during the final hours of shell formation inside the hen’s oviduct. The presence or absence of pigments determines the final color.

Two primary pigments are responsible for natural eggshell hues:

- Protoporphyrin IX – derived from hemoglobin, this compound creates brown, rust, or reddish tones.

- Biliverdin – a bile pigment that produces blue or green shades.

White eggs lack both pigments. The genetic makeup of the chicken dictates whether and how much of these pigments are secreted during shell calcification. This process occurs over approximately 20 hours, with pigment deposition happening in the last 3–5 hours before the egg is laid.

“Eggshell color is a genetically controlled trait, closely linked to breed and earlobe appearance.” — Dr. Karen Hart, Poultry Science Researcher, University of California

Chicken Breed and Earlobe Clue

One of the most reliable predictors of eggshell color is the breed of the hen. While exceptions exist, a general rule holds true: hens with white earlobes tend to lay white eggs, while those with red or dark earlobes usually lay brown ones.

| Breed | Earlobe Color | Typical Egg Color | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leghorn | White | White | Most common commercial white-egg layer |

| Rhode Island Red | Red | Rich Brown | Popular backyard and farm breed |

| Araucana | Pink | Blue or Green | Natural biliverdin producers |

| Marans | Dusky | Dark Chocolate Brown | Pigment intensity varies by strain |

| Plymouth Rock | Red | Light to Medium Brown | Hardy dual-purpose breed |

This correlation between earlobe and egg color stems from shared developmental pathways in pigment production. However, it's not foolproof—some hybrid breeds blur the lines, and environmental factors can influence shade intensity.

Debunking Myths: Nutrition, Taste, and Quality

A persistent myth suggests that brown eggs are more nutritious, organic, or tastier than white eggs. This belief likely arose because many free-range or heritage-breed hens lay brown eggs, creating an association between shell color and farming practices. However, scientific studies confirm that shell color does not affect nutritional value, flavor, or cooking performance.

The interior quality of an egg—yolk color, protein content, and freshness—is influenced by the hen’s diet, age, and living conditions, not by the pigmentation of the shell. A white-egg-laying hen fed a high-quality diet will produce eggs just as nutritious as those from a brown-egg layer on the same feed.

In commercial settings, Leghorns (white-egg layers) dominate large-scale operations due to their efficiency, high laying rate, and lower feed consumption. This efficiency makes white eggs widely available and often less expensive, reinforcing—but not causing—the misconception that they are \"lesser.\"

Unusual Egg Colors: Blue, Green, and Speckled Shells

Beyond white and brown, some breeds produce truly unique eggs. Araucanas, Ameraucanas, and Easter Eggers are known for laying blue or green eggs thanks to biliverdin, which permeates the entire shell rather than just coating the surface. This means even if the egg is cracked or scratched, the blue color persists through the shell’s thickness.

Other breeds, like Marans or Welsummers, lay eggs so dark they appear almost chocolate-colored. These rich browns result from heavy protoporphyrin deposition. Some hens also lay speckled or mottled eggs, where pigment distribution is uneven—a harmless variation influenced by stress, age, or temporary disruptions in the oviduct.

Interestingly, crossbreeding can yield “Easter Egg” hybrids that lay a mix of colors—blue, pinkish, olive, or speckled—depending on inherited genes. These novelty layers are popular among small-scale farmers and hobbyists seeking visual variety.

Step-by-Step: How Pigment Is Applied During Egg Formation

- Day 1, 0–5 hrs: Yolk released from ovary into oviduct.

- 5–10 hrs: Albumen (egg white) added in the magnum section.

- 10–15 hrs: Shell membranes form in the isthmus.

- 15–19 hrs: Calcium carbonate builds the initial white shell in the uterus (shell gland).

- 19–24 hrs: Final pigmentation applied—protoporphyrin for brown, biliveradin for blue/green.

- 24–26 hrs: Egg is laid via the cloaca.

This timeline shows why pigment only affects the outermost layer in brown eggs—it’s applied late in the process. Blue eggs are different: biliverdin integrates earlier, making the color structural.

Practical Checklist for Consumers and Farmers

Whether you're buying eggs at the store or raising your own flock, here’s how to make informed decisions about eggshell color:

- ✅ Don’t judge egg quality by shell color—check expiration dates and refrigeration instead.

- ✅ For backyard flocks, choose breeds based on climate hardiness, temperament, and laying frequency—not just egg color.

- ✅ Store all eggs pointy-end down to keep the air cell stable and yolk centered.

- ✅ Wash eggs only when necessary; commercial washing removes the natural bloom that protects against bacteria.

- ✅ Rotate stock regularly to ensure freshness, especially with mixed-color batches.

Farm Case Study: The Rainbow Egg Stand at Greenfield Market

At Greenfield Farmers Market, vendor Maria Torres runs a popular stall known for its colorful egg cartons. She keeps five breeds: White Leghorns, Rhode Island Reds, Ameraucanas, Barred Plymouth Rocks, and a few Easter Eggers. Her customers often ask why prices vary slightly between colors.

Maria explains that her Ameraucanas require more feed and lay fewer eggs than her Leghorns, which impacts cost. She uses egg color as an educational tool, teaching customers that blue doesn’t mean healthier, just genetically distinct. Over time, her transparency has built trust—and increased sales across all varieties.

“People love the surprise of cracking open a green-tinted egg,” she says. “But once they learn the science, they stop assuming one type is better. They just enjoy the diversity.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Do white eggs taste different from brown or colored eggs?

No. Taste is determined by the hen’s diet, not shell color. A corn-fed hen will produce a richer-tasting yolk regardless of whether the shell is white, brown, or blue.

Can a chicken change the color of the eggs it lays?

Not fundamentally. A white-egg breed won’t suddenly lay brown eggs. However, individual hens may lay lighter or darker brown eggs as they age, due to reduced pigment production. Stress or illness can also cause temporary paleness or blotchiness.

Are blue or green eggs healthier?

No. Despite their striking appearance, blue and green eggs have the same nutritional profile as white or brown eggs. The biliverdin pigment is harmless and does not enhance health benefits.

Conclusion: Embracing Diversity in the Egg Basket

Eggshell color is a beautiful example of nature’s genetic artistry. From the stark white of a Leghorn egg to the sky-blue of an Araucana, each hue tells a story of breed heritage and biological precision. Understanding the science behind these differences empowers consumers to make choices based on facts, not myths, and encourages farmers to appreciate the unique traits of their flocks.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?