For decades, hurricanes, typhoons, and tropical storms have carried human names—Katrina, Sandy, Haiyan, Ian. These names make headlines, evoke emotion, and help us remember some of the most powerful natural events in history. But why do we name storms after people? How did this practice begin, and what rules govern it today? The answer lies in a blend of practical necessity, historical precedent, and evolving meteorological science.

The Origins of Naming Storms

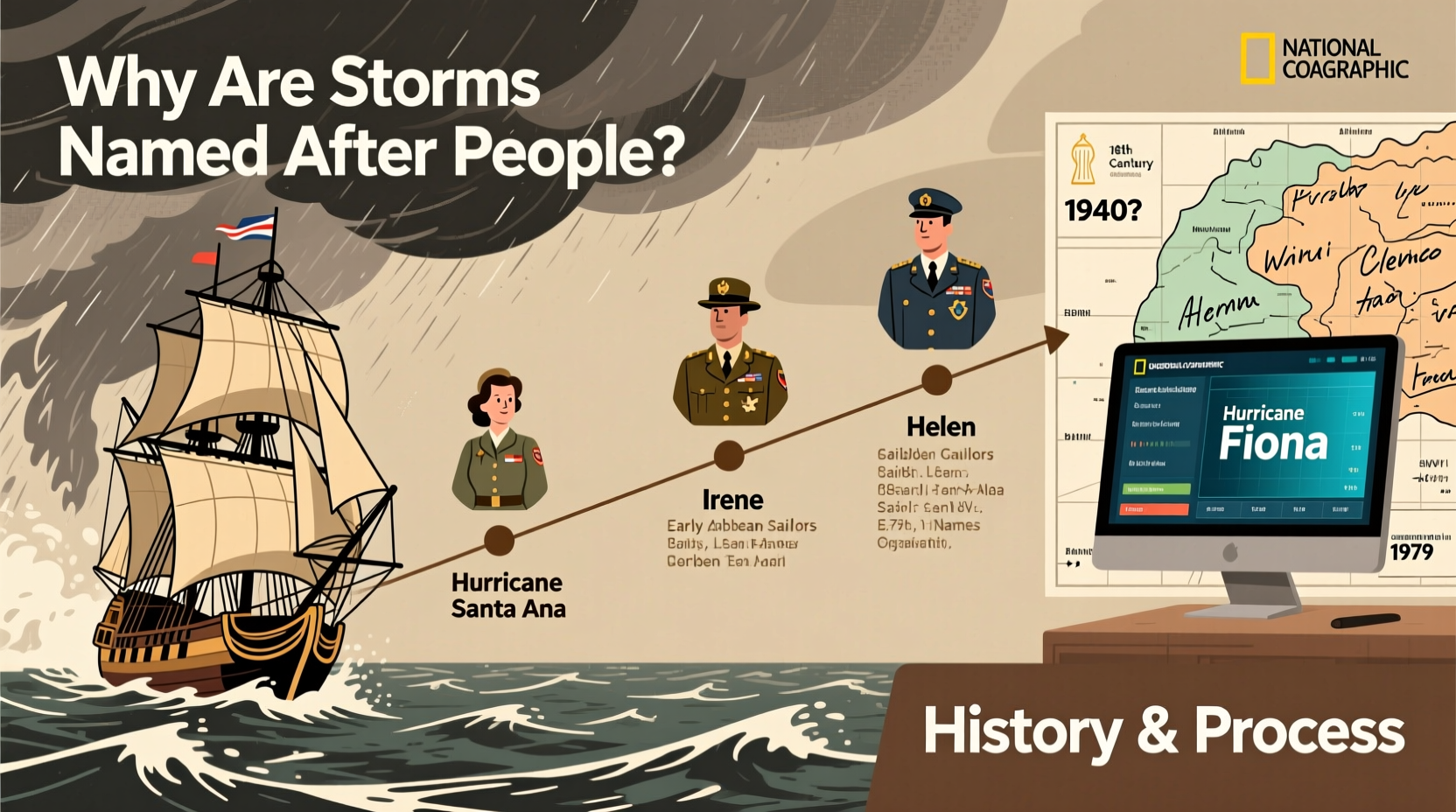

Before the 20th century, tropical cyclones were often identified by their location, date, or impact. A storm might be called “the Great Galveston Hurricane of 1900” or “the Labor Day Storm.” While descriptive, these titles were unwieldy and imprecise, especially when multiple storms occurred simultaneously.

The first known use of personal names for storms came from Australian meteorologist Clement Wragge in the late 1800s. Between 1887 and 1907, Wragge whimsically named storms after mythological figures, politicians he disliked, and even family members. When his funding was cut, he famously named a storm “W.M. Hughes”—after the Australian politician who opposed his work—as a form of protest.

Though Wragge’s system faded after his retirement, the idea lingered. During World War II, Allied meteorologists began informally naming Pacific typhoons after their wives and girlfriends. This practice helped pilots and sailors communicate more clearly about storm positions without confusion. By the 1950s, the U.S. National Hurricane Center (NHC) adopted formal naming to improve public awareness and streamline warnings.

Why Names Work Better Than Numbers

Imagine trying to follow two hurricanes forming in the Atlantic at the same time: Tropical Depression Seven and Tropical Storm Eight. Without distinct identities, confusion increases among forecasters, emergency managers, and the public. Names solve this problem by providing clarity and consistency.

Research from the American Meteorological Society shows that named storms receive greater media coverage and public attention. A name makes a storm feel more real, increasing the likelihood that people will heed evacuation orders and prepare adequately.

“Using short, distinctive names reduces confusion in warning messages and helps save lives.” — National Hurricane Center, NOAA

In addition, names aid in historical record-keeping. Revisiting past storms like Hurricane Andrew (1992) or Super Typhoon Mangkhut (2018) becomes easier when they carry unique identifiers rather than technical designations.

How Storms Are Named Today: A Global System

Today, storm naming is managed by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), which oversees rotating lists of names for different ocean basins. Each region maintains its own list, updated every six years unless a name is retired due to extreme damage or loss of life.

In the Atlantic basin, there are 21 assigned names each season (excluding Q, U, X, Y, Z due to limited phonetic availability). Names alternate between male and female, a change implemented in 1979 to promote gender equality after decades of exclusively female-named storms.

Atlantic Hurricane Name List (Example Cycle: 2024–2029)

| Year | Names (Male/Female Alternating) |

|---|---|

| 2024 | Alexandra, Bret, Cindy, Don, Emily, Franklin, Gert, Harold, Idalia, Jose, Katia, Lee, Margot, Nigel, Ophelia, Philippe, Rosa, Sean, Tamika, Vince, Whitney |

| 2025 | Andrea, Barry, Chantal, Dennis, Emily, Floyd, Gabrielle, Humberto, Imelda, Josephine, Kyle, Laura, Marco, Nana, Omar, Paulette, Rene, Sally, Teddy, Vicky, Wilfred |

If more than 21 named storms occur in a single season, as happened in 2005 and 2020, the Greek alphabet was previously used. However, due to confusion with similar-sounding names (e.g., Beta and Eta), the WMO discontinued this practice in 2021. Now, a supplemental list of regular names is used instead.

Retiring Storm Names: When a Name Is Too Infamous

Not all storm names live to see another rotation. If a hurricane causes significant death or destruction, its name is permanently retired out of respect for victims and to avoid confusion in future discussions.

Since 1954, over 90 Atlantic storm names have been retired. Some of the most notable include:

- Katrina (2005) – Devastated New Orleans and the Gulf Coast, resulting in over 1,800 deaths.

- Harvey (2017) – Brought catastrophic flooding to Houston, Texas.

- Dorian (2019) – Ravaged the Bahamas with Category 5 winds.

- Ian (2022) – Caused widespread destruction across Florida and contributed to over $110 billion in damages.

The retirement process is decided during annual WMO meetings. Member countries affected by the storm can request removal, and the decision is made by consensus.

Mini Case Study: The Retirement of Hurricane Katrina

In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina formed over the Bahamas and rapidly intensified into a Category 5 storm. Though it weakened slightly before landfall, its storm surge overwhelmed levees in New Orleans, submerging 80% of the city. Emergency response failures, displacement of hundreds of thousands, and long-term economic impacts made Katrina one of the costliest and deadliest hurricanes in U.S. history.

In spring 2006, the WMO officially retired the name “Katrina.” Since then, no future Atlantic storm will bear that name. Instead, it stands as a permanent marker in meteorological and cultural memory—a reminder of both nature’s power and the importance of preparedness.

Global Variations in Storm Naming

While the Atlantic uses Western-style personal names, other regions apply different conventions based on local culture and language.

- Western North Pacific (Typhoons): Uses names contributed by 14 nations, including animals (Neoguri), flowers (Peipah), and mythological figures (Kammuri).

- North Indian Ocean: Names are proposed by India, Bangladesh, Maldives, and others—often reflecting virtues (Hikaa means “twist”) or natural elements.

- Australia and Fiji: Combine English, Indigenous, and regional names (e.g., Ita, Zena).

This international approach fosters collaboration and inclusivity while maintaining clarity in communication across borders.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why aren’t all storms named?

Only tropical or subtropical cyclones that reach sustained wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h) are given names. Lesser systems are classified as depressions and tracked numerically.

Can anyone suggest a storm name?

In most regions, only WMO member nations submit names. However, some agencies run public contests for supplemental lists or educational outreach.

Do storm names influence perception?

Yes. Studies suggest that people take female-named storms less seriously, though this bias has decreased over time. More importantly, memorable names increase public engagement with safety messaging.

Actionable Checklist: Staying Informed During Storm Season

- Review the current year’s storm name list from the National Hurricane Center.

- Sign up for local weather alerts via SMS or emergency apps.

- Know whether your area is prone to hurricanes, typhoons, or cyclones.

- Check if any recently retired names affect your region’s history.

- Update your emergency kit and evacuation plan annually.

Conclusion: Names That Carry Meaning Beyond the Wind

Storms are named not for tradition alone, but for survival. What began as a quirky habit of an eccentric meteorologist evolved into a global standard that enhances communication, improves disaster response, and honors those affected by tragedy. Each name serves as both a label and a legacy—tying meteorology to memory, science to society.

As climate change contributes to longer and more intense storm seasons, understanding the meaning behind these names becomes even more vital. Knowing why we call a storm “Idalia” or retire “Ian” isn’t just trivia—it’s part of building a safer, more resilient world.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?