At the heart of every spoken language lies a small but powerful set of sounds: vowels. They form the core of syllables, give words their shape, and allow our voices to carry meaning across time and culture. But what makes a vowel a vowel? Why do we classify certain sounds as vowels while excluding others? The answer stretches far beyond the alphabet—it reaches into anatomy, acoustics, and the ancient roots of human communication. To truly understand why vowels are vowels, we must examine not just how they sound, but how they function, where they came from, and why they remain indispensable to speech.

The Linguistic Definition of a Vowel

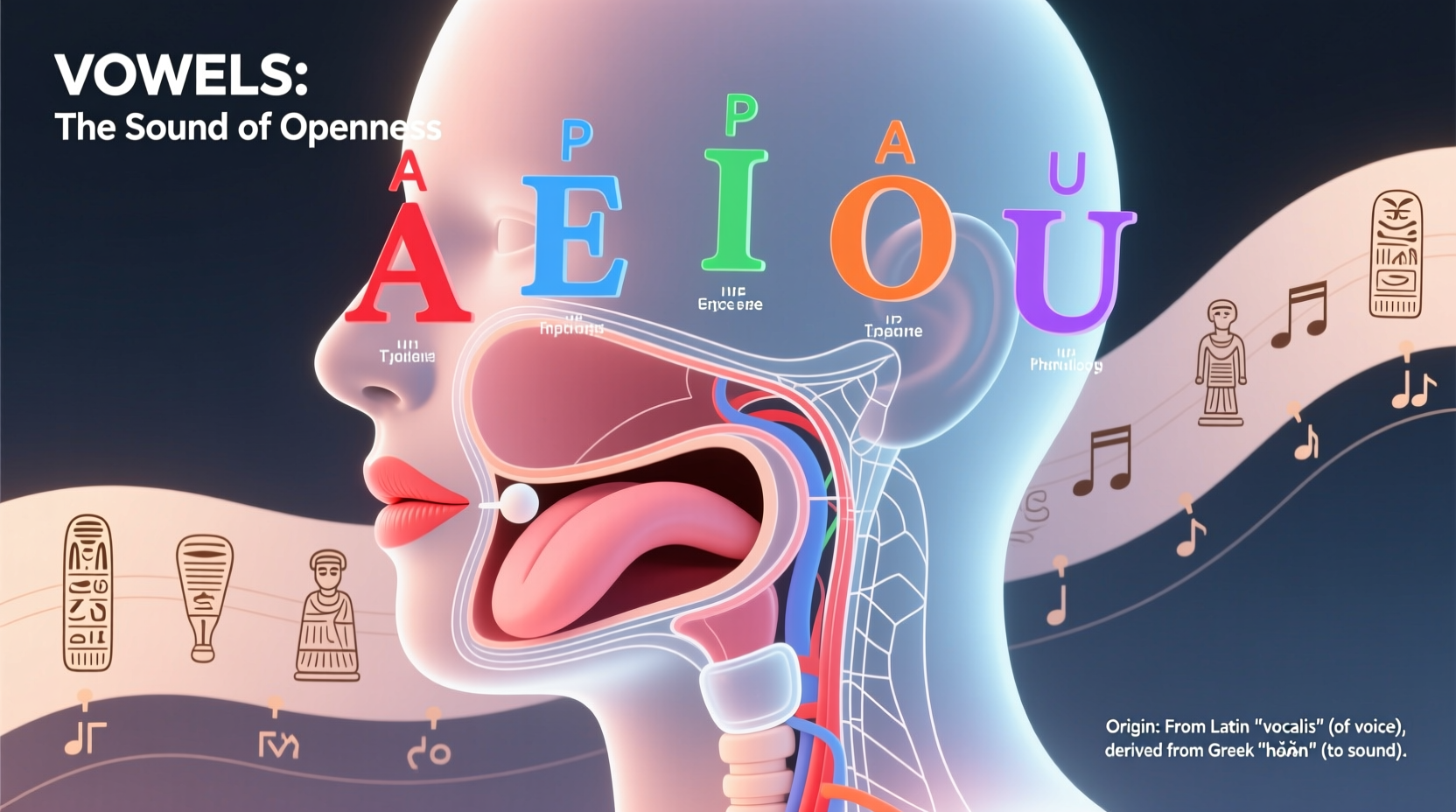

In phonetics, a vowel is defined by how it is produced. Unlike consonants, which involve some degree of obstruction in the vocal tract—such as the lips closing, the tongue touching the palate, or airflow being constricted—vowels are characterized by an open configuration of the mouth and throat. When producing a vowel, air flows freely from the lungs through the larynx and out of the mouth without significant turbulence or blockage.

This open vocal tract allows the sound generated by the vibrating vocal folds to resonate within the oral cavity. The unique quality of each vowel comes from subtle changes in the position of the tongue, the shape of the lips, and the openness of the jaw. For example:

- /i/ as in “see” – high front tongue, spread lips

- /ɑ/ as in “father” – low back tongue, open jaw

- /u/ as in “food” – high back tongue, rounded lips

These variations create distinct resonant frequencies, known as formants, which listeners interpret as different vowel sounds. Crucially, vowels serve as the nucleus of syllables. In the word “cat,” /æ/ is the vowel that anchors the syllable between the consonants /k/ and /t/. Without a vowel-like center, most words would collapse into unintelligible bursts of noise.

Historical Origins: From Ancient Scripts to Modern Letters

The term “vowel” itself comes from the Latin word *vocalis*, meaning “speaking” or “uttering voice.” The English word evolved via Old French *voel* and ultimately traces back to the Proto-Indo-European root *wekw-*, “to speak.” This etymology reflects the fundamental link between vowels and voiced sound—they are the carriers of tone and melody in speech.

But written vowels are a relatively late innovation in human writing systems. Early scripts like Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs were primarily consonantal; they recorded the skeleton of words but left vowel interpretation to context and memory. It wasn’t until the development of the Phoenician alphabet around 1050 BCE that symbols for consonants became standardized—and even then, vowels remained unmarked.

The Greeks revolutionized writing by adapting Phoenician letters to represent vowel sounds. Around the 8th century BCE, they repurposed Phoenician consonant symbols—such as ‘aleph’ (originally /ʔ/)—into the vowel /a/, creating the first true alphabetic system with both consonants and vowels. This innovation allowed for more precise pronunciation and laid the foundation for Latin, Cyrillic, and many modern alphabets.

“The Greek addition of vowels was not just orthographic progress—it was cognitive liberation. For the first time, readers could reconstruct speech exactly as intended.” — Dr. Lila Fernández, Historical Linguist, University of Edinburgh

Why These Sounds Became Vowels: An Evolutionary Perspective

From an evolutionary standpoint, vowels likely emerged because they are acoustically robust and easy to produce. Human infants begin cooing with vowel-like sounds such as [a], [u], and [i] long before forming complex words. These sounds require minimal coordination and are highly perceptible across distances and background noise—key advantages in early communication.

Vowels also maximize acoustic energy. Because there is no constriction in the vocal tract, the sound waves travel efficiently and can be modulated easily through pitch and duration. This made them ideal for expressive functions: signaling emotion, marking questions, or emphasizing parts of speech.

Over millennia, languages converged on a common set of vowel contrasts—typically five to seven core vowels—because this range strikes a balance between clarity and efficiency. Too few vowels increase ambiguity; too many demand excessive precision in articulation and perception. The so-called “cardinal vowels,” established by linguist Daniel Jones in the early 20th century, map this universal space and are used to describe vowel systems across languages.

How Vowels Function Across Languages: A Comparative Table

| Language | Number of Vowels | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|

| English | 14–20+ (depending on dialect) | Rich in diphthongs (e.g., /aɪ/, /oʊ/); variable pronunciation |

| Spanish | 5 | Clean, consistent vowel values; minimal reduction in unstressed syllables |

| Japanese | 5 | Pure vowels; each corresponds directly to a kana character |

| Finnish | 8 | Vowel harmony: front and back vowels don’t mix in a word |

| Hawaiian | 5 | Only eight letters in the alphabet; vowels dominate syllable structure |

This variation shows that while all spoken languages use vowels, the number and behavior of these sounds depend on historical, phonological, and cultural factors. Some languages, like Arabic, use short and long vowel distinctions to change meaning (e.g., *darasa* vs. *dārasa*), while others, like French, employ nasalized vowels (/ɛ̃/ in “vin”) absent in English.

Common Misconceptions About Vowels

Many people confuse letters with sounds. In English, the letters A, E, I, O, U (and sometimes Y) are called “vowel letters,” but they don’t always represent vowel sounds. For instance:

- In “gym,” Y represents the vowel /ɪ/.

- In “cough,” O is silent—no vowel sound is derived from it.

- In “queen,” the letter Q is followed by U, but the vowel sound /iː/ comes from E.

Conversely, consonant letters can represent vowel-like functions. In “rhythm,” both Y and H play roles in forming the syllabic peak, even though neither is traditionally a vowel letter.

Mini Case Study: Teaching Vowels to Language Learners

Sophie, a Spanish speaker learning English, struggled to distinguish between the vowels in “ship” (/ɪ/) and “sheep” (/iː/). In Spanish, there is only one close front vowel, making the contrast unfamiliar. Her teacher used minimal pair drills—words that differ by only one sound—and mirror exercises to help her feel the subtle differences in tongue height and duration. Over six weeks, Sophie improved significantly by focusing on auditory discrimination and muscle memory. This case illustrates how understanding vowel mechanics can accelerate language acquisition.

Practical Checklist: Identifying and Using Vowels Correctly

- Listen for syllable peaks: Identify which sound forms the core of each syllable.

- Sustain the sound: Try holding individual sounds—only vowels can be prolonged smoothly.

- Check for vocal tract openness: No major obstructions should occur during production.

- Use IPA symbols: Learn basic International Phonetic Alphabet notation to avoid confusion from spelling.

- Practice with minimal pairs: Improve perception and production through contrastive examples (e.g., “bat” vs. “bet”).

Frequently Asked Questions

Are all vowels voiced?

Yes, all vowels in normal speech are voiced, meaning the vocal folds vibrate during their production. While it's technically possible to whisper a vowel (producing it without voicing), the defining feature remains the open vocal tract configuration.

Can consonants act like vowels?

In rare cases, yes. Sounds like /l/, /n/, and /r/ can become syllabic—acting as the nucleus of a syllable—especially in fast speech. For example, the second syllable in “bottle” is often pronounced as a syllabic /l̩/. However, these are still classified as consonants due to their manner of articulation.

Why does English have so many vowel sounds?

English has undergone significant historical shifts, including the Great Vowel Shift (15th–18th centuries), which altered the pronunciation of long vowels dramatically. Combined with borrowings from French, Latin, and Germanic languages, this created a complex and irregular vowel system that doesn't always align with spelling.

Conclusion: Embracing the Power of Vowels

Vowels are more than just letters on a page—they are the lifeblood of spoken language. Their origins lie in the earliest human utterances, their functions are essential to syllable structure, and their evolution reflects the adaptability of communication. Whether you're a language learner, educator, or simply curious about how speech works, understanding why vowels are vowels unlocks deeper insight into how we express thought, emotion, and identity through sound.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?