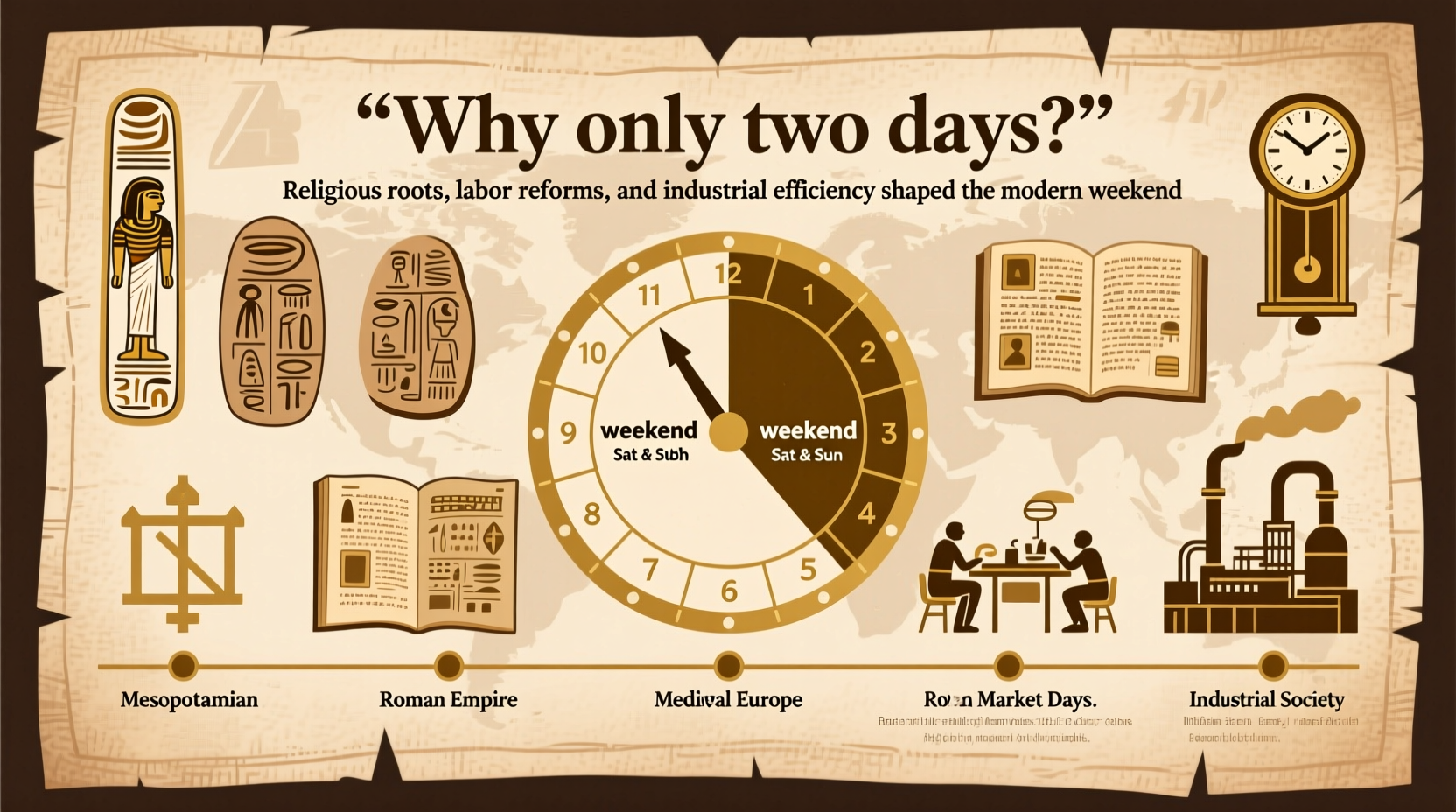

The modern weekend—Saturday and Sunday off from work—is so deeply embedded in daily life that most people rarely question its origin. Yet the idea of a two-day break is neither natural nor ancient. It’s the product of centuries of cultural, religious, and industrial evolution. Understanding why weekends are only two days long requires tracing a path from ancient religious observances to labor movements and global economic shifts. The answer lies not in biology or nature, but in human institutions and societal compromise.

Origins in Religious Tradition

The concept of a weekly rest day dates back thousands of years. Ancient civilizations observed periodic days of rest, often tied to lunar cycles or religious rituals. However, the earliest known structured weekly rhythm comes from Judaism. The Sabbath—a day of rest beginning Friday evening and ending Saturday night—is mandated in the Torah as a holy day of cessation from labor. This seven-day cycle, rooted in the Genesis creation story, influenced both Christianity and Islam.

Early Christians shifted the day of rest to Sunday, commemorating the resurrection of Jesus Christ. By the 4th century, Roman Emperor Constantine officially designated Sunday as a day of rest across the Roman Empire. Yet for centuries, this was more of a religious observance than a widespread labor practice. Most people, especially in agrarian societies, worked six or even seven days a week out of necessity.

“Religion gave us the idea of a weekly rest, but economics determined how long it would last.” — Dr. Miriam Chen, Historian of Labor Practices

The Industrial Revolution and the Birth of the Modern Weekend

The real transformation began during the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries. Factory workers faced grueling schedules—often 12 to 16 hours a day, six or seven days a week. In response, labor reformers began advocating for shorter workweeks. One of the earliest victories came in 1840, when Welsh industrialist Robert Owen championed the “eight-hour workday, eight hours recreation, eight hours rest” slogan. Though not immediately adopted, his ideas gained traction over time.

A key milestone occurred in the early 20th century. In 1908, a mill in New England became the first U.S. company to institute a five-day, 40-hour workweek to accommodate Jewish workers who observed the Saturday Sabbath. This experiment proved successful: productivity remained stable, and worker morale improved. Henry Ford followed suit in 1926, closing his factories on Saturdays and Sundays. He didn’t do it purely out of benevolence; he believed rested workers would buy more consumer goods, fueling economic growth.

Global Standardization and Economic Constraints

Despite growing momentum, the two-day weekend wasn’t universal until much later. The U.S. Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 helped codify the 40-hour workweek, but many industries still operated on six-day schedules into the 1950s. Meanwhile, in the Soviet Union, the government experimented with five-day and even four-day workweeks in the 1920s and 30s, but these were abandoned due to logistical chaos and reduced productivity.

Why did two days become the standard instead of three or four? Economics played a decisive role. Employers resisted longer weekends because they feared reduced output and higher labor costs. A two-day break struck a balance: enough rest to maintain worker health and morale, while preserving production capacity. As globalization intensified, countries aligned their workweeks to remain competitive in international trade and manufacturing.

| Country | Standard Weekend | Historical Shift |

|---|---|---|

| United States | Saturday–Sunday | Fully adopted by 1940s |

| United Kingdom | Saturday–Sunday | Gradual shift from 19th-century half-Saturdays |

| Iran | Thursday–Friday | Reflects Islamic Friday prayers |

| United Arab Emirates | Saturday–Sunday (since 2022) | Shifted from Friday–Saturday to align with global markets |

| India | Sunday (most sectors), some Saturday half-days | Mixed model due to diverse industries |

Could We Have Longer Weekends?

Today, the two-day weekend remains the norm, but it's increasingly questioned. With advances in automation, artificial intelligence, and productivity tools, some economists argue we could afford a shorter workweek without sacrificing output. Pilot programs in Iceland, Scotland, and Japan have tested four-day workweeks with promising results: higher employee satisfaction, lower burnout, and no drop in productivity.

Yet structural barriers persist. Many service-sector jobs—retail, healthcare, hospitality—require weekend staffing. Fully shifting to a three-day weekend would require complex scheduling, higher labor costs, or automation investments. Additionally, cultural expectations around availability and performance pressure discourage widespread change.

Step-by-Step: How the Two-Day Weekend Took Hold

- Religious Foundations: Sabbath observance establishes the seven-day cycle with one day of rest.

- Industrial Exploitation: 18th–19th century factory workers endure near-constant labor.

- Labor Advocacy: Reformers demand shorter hours and humane conditions.

- Captive Experiments: Companies like Ford test two-day weekends and see benefits.

- Legal Codification: Governments adopt 40-hour workweek standards.

- Global Alignment: Nations standardize weekends to facilitate trade and communication.

Real-World Example: The UAE’s Weekend Reform

In 2022, the United Arab Emirates made headlines by shifting its official weekend from Friday–Saturday to Saturday–Sunday. This change wasn’t driven by worker fatigue or social reform, but by economic strategy. As a global business hub, the UAE found its traditional weekend misaligned with international partners in Europe and Asia. By adopting the Saturday–Sunday break, Emirati businesses could coordinate meetings, process transactions, and engage in real-time collaboration without delays.

This case illustrates a critical point: the length and timing of weekends are not fixed by tradition alone, but constantly reshaped by economic priorities. Even in culturally conservative nations, practicality can override longstanding customs.

Expert Insight on the Future of Work

“We’re clinging to a 20th-century work model in a 21st-century economy. The two-day weekend made sense when factories dominated, but today’s knowledge work doesn’t require rigid schedules. Flexibility and recovery matter more than uniform days off.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Organizational Psychologist at MIT Sloan

FAQ

Why don’t we have three-day weekends everywhere?

While desirable, three-day weekends increase operational costs and complicate staffing in essential services. Without major productivity gains or automation, most economies view longer weekends as economically unfeasible.

Is Sunday the only universal day off?

No. While Sunday is common, many Muslim-majority countries observe Friday as a primary rest day, and Israel observes Saturday. Globalization is pushing some nations to adjust their weekends for better alignment with trading partners.

Did any country successfully implement a four-day workweek?

Iceland ran a large-scale trial between 2015 and 2019 involving over 2,500 workers. Results showed no loss in productivity, and many organizations permanently adopted shorter hours. Similar pilots in Japan and Canada show potential, but full national adoption remains limited.

Actionable Checklist: Rethinking Your Weekend

- Use your two-day break strategically: dedicate one day to recovery, one to meaningful activities.

- Advocate for flexible hours at work if your role allows it.

- Support companies experimenting with shorter workweeks.

- Track your energy levels to identify optimal rest patterns.

- Push for policy discussions on work-life balance in your community or workplace.

Conclusion

The two-day weekend is not a law of nature, but a historical compromise between spiritual tradition, labor rights, and economic pragmatism. It emerged slowly, fought for by workers and validated by forward-thinking employers. While it may seem set in stone, history shows that the structure of our workweek is always evolving. As technology reshapes how we produce value, the possibility of longer weekends or more flexible schedules grows closer.

The next shift won’t come from corporate goodwill alone—it will require public awareness, policy innovation, and collective demand. If you’ve ever wondered why weekends feel too short, remember: they were negotiated, not ordained. And like all social agreements, they can be renegotiated.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?