At first glance, whales may seem like giant fish gliding effortlessly through the ocean. Their streamlined bodies, aquatic habitat, and tail fins resemble those of sharks and other marine species. But despite their watery world, whales are not fish—they are mammals. This classification is based on fundamental biological traits shared with humans, dogs, and bats. Understanding why whales are mammals reveals a fascinating story of evolution, adaptation, and survival in Earth’s oceans.

What Defines a Mammal?

Mammals are a class of vertebrates characterized by several distinct features. These traits set them apart from reptiles, birds, amphibians, and fish. The most well-known mammalian characteristics include:

- Warm-bloodedness (endothermy): Mammals maintain a constant internal body temperature regardless of their environment.

- Live birth (viviparity): Most mammals give birth to live young rather than laying eggs.

- Milk production: Females nurse their young using mammary glands.

- Presence of hair or fur: Even minimal, often at some stage of life.

- Advanced brains: Highly developed neocortex associated with complex behaviors.

- Lungs for breathing air: All mammals must surface to breathe oxygen.

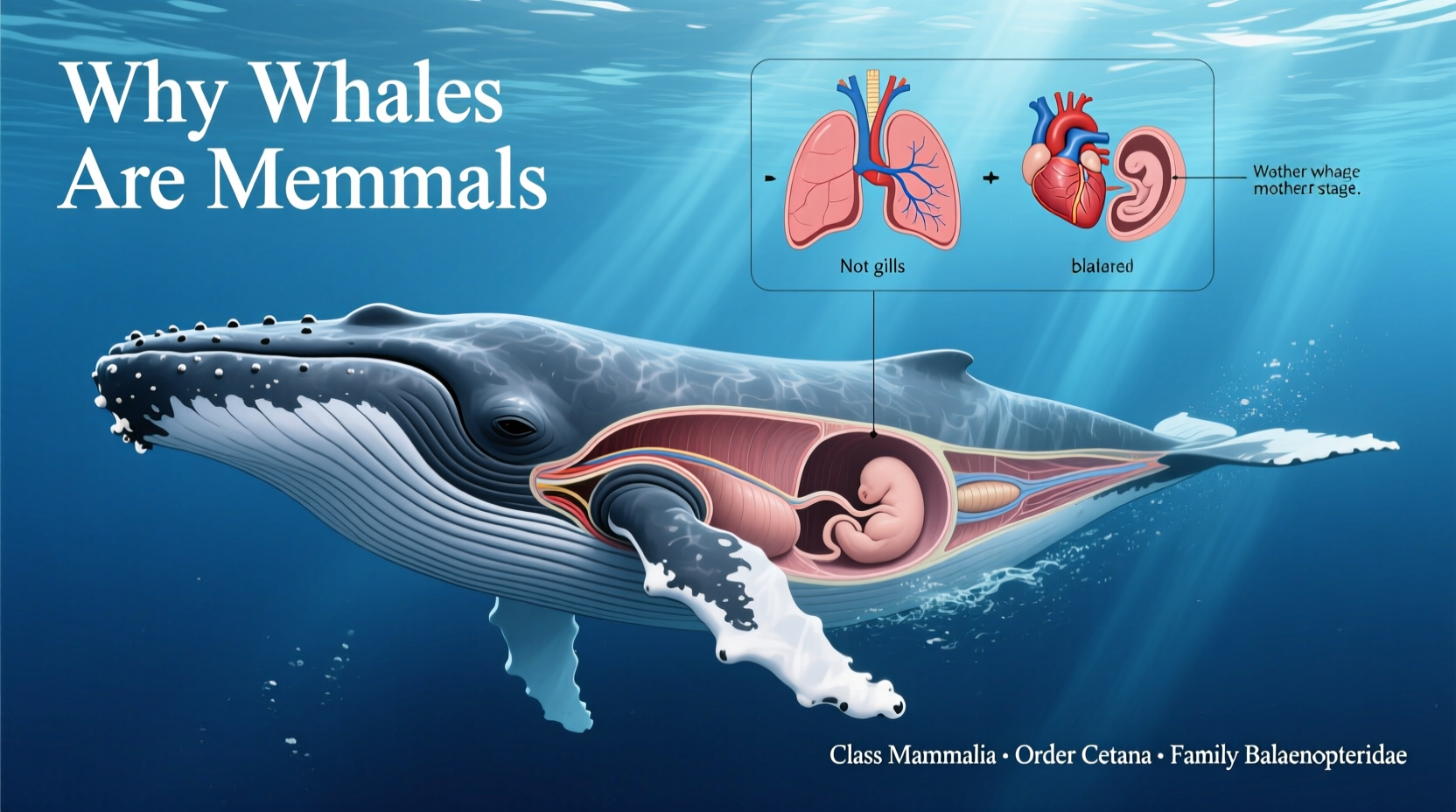

Whales meet every one of these criteria—despite spending their entire lives in water. This makes them part of the mammalian lineage, specifically within the order Cetacea, which includes dolphins and porpoises.

Anatomy and Physiology: How Whales Breathe and Stay Warm

One of the most obvious differences between whales and fish is how they breathe. Fish extract oxygen from water using gills, but whales have lungs and must come to the surface to inhale air through blowholes located on top of their heads. A humpback whale, for example, can hold its breath for up to 45 minutes during deep dives, but eventually must return to the surface to exhale and inhale—a process visible as a spout of misty vapor.

Despite living in cold ocean waters, whales maintain a stable internal temperature around 36–37°C (97–99°F), similar to humans. They achieve this through a thick layer of blubber beneath the skin. Blubber serves multiple purposes:

- Insulation against cold water

- Energy reserve during long migrations

- Buoyancy control

- Streamlining the body for efficient swimming

This layer can be up to 50 cm (20 inches) thick in some species, such as the bowhead whale. Unlike fish, which rely on ambient water temperature, whales actively regulate their body heat—an essential trait of endothermic mammals.

Evidence of Mammalian Reproduction and Parenting

Whales reproduce sexually and give birth to live calves after lengthy gestation periods. For instance:

| Whale Species | Gestation Period | Calving Interval | Nursing Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Whale | 10–12 months | 2–3 years | 6–7 months |

| Humpback Whale | 11 months | 2–3 years | 6–10 months |

| Sperm Whale | 14–16 months | 4–6 years | Up to 2 years |

After birth, mother whales nurse their calves with nutrient-rich milk that can be over 35% fat—far richer than cow’s milk. Calves grow rapidly, gaining hundreds of pounds per month. Sperm whale calves, for example, drink about 30 gallons of milk daily during peak nursing.

“We see strong maternal bonds in whales, including protection, teaching, and prolonged care—hallmarks of mammalian social structure.” — Dr. Naomi Pierce, Marine Biologist, Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Evolutionary Origins: From Land to Sea

The idea that whales were once land-dwelling animals might sound surprising, but fossil evidence confirms this remarkable transition. Around 50 million years ago, the ancestors of modern whales were small, four-legged, hoofed mammals resembling deer or tapirs. One key fossil, *Pakicetus*, discovered in Pakistan, shows skull features identical to early whales but lived near rivers and could walk on land.

Over millions of years, these creatures adapted to aquatic life:

- Limb transformation: Front legs evolved into flippers; hind limbs regressed and became vestigial.

- Nostril migration: Nostrils moved from the front of the snout to the top of the head, forming blowholes.

- Tail development: Horizontal tail flukes evolved for powerful up-and-down propulsion.

- Sensory adaptation: Hearing shifted to underwater echolocation in toothed whales (e.g., orcas).

DNA analysis further supports this evolutionary path. Whales share a common ancestor with hippos, both descending from artiodactyls—the even-toed ungulates. This genetic link reinforces their place in the mammalian tree of life.

Common Misconceptions About Whales and Fish

Because whales live entirely in water, many people assume they are fish. However, this confusion overlooks critical biological distinctions. Consider the following comparison:

| Feature | Whales (Mammals) | Fish |

|---|---|---|

| Breathing Method | Lungs – must surface to breathe | Gills – extract oxygen from water |

| Body Temperature | Warm-blooded | Cold-blooded |

| Reproduction | Live birth, extended parental care | Most lay eggs, minimal care |

| Skin/Covering | Smooth skin with sparse hair at birth | Scales |

| Tail Orientation | Horizontal flukes | Vertical tail fin |

These differences highlight that appearance alone can be misleading. Evolution has shaped whales to thrive in water, but their biology remains unmistakably mammalian.

Conservation and Why Classification Matters

Understanding that whales are mammals isn’t just academic—it has real-world implications for conservation. Because they are warm-blooded, long-lived, and slow to reproduce, whale populations recover slowly from threats like whaling, ship strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, and ocean noise pollution.

For example, the North Atlantic right whale has fewer than 350 individuals remaining. With females giving birth only once every 3–5 years, each death significantly impacts population viability. Recognizing whales as intelligent, socially complex mammals fosters greater empathy and stronger legal protections under laws like the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do whales have hair?

Yes, but very little. Most whale species have a few sensory hairs around the snout or chin, especially at birth. These whisker-like structures help detect movement in water and are remnants of their terrestrial ancestry.

Can whales drown?

Technically, yes—if prevented from reaching the surface to breathe. Newborn calves can struggle in rough seas, and entangled whales may exhaust themselves trying to surface. Unlike fish, whales cannot extract oxygen from water and will suffocate if submerged too long.

Are dolphins also mammals?

Absolutely. Dolphins are members of the same order—Cetacea—as whales. In fact, all dolphins and porpoises are considered toothed whales. They share the same mammalian traits: live birth, milk production, warm-bloodedness, and air breathing.

Conclusion: Respecting the Giants of the Deep

Whales are not merely large sea creatures—they are highly evolved mammals that represent one of nature’s most extraordinary transitions from land to water. Their classification as mammals reflects deep biological truths about reproduction, respiration, thermoregulation, and intelligence. By recognizing whales for what they truly are, we deepen our appreciation for their complexity and strengthen our commitment to protecting them.

Next time you see a spout rising from the ocean or hear the haunting song of a humpback, remember: you’re witnessing a warm-blooded, nurturing, air-breathing mammal navigating a vast aquatic world. That understanding transforms awe into respect—and respect into action.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?