Self-directed learning is often praised as a hallmark of personal growth, adaptability, and lifelong development. Yet, despite access to vast online resources and flexible learning platforms, many individuals still struggle to take charge of their own education. The gap between intention and action reveals deeper psychological, structural, and environmental barriers. Understanding why some people aren’t self-learners isn’t about assigning blame—it’s about identifying real obstacles so they can be overcome.

The Myth of Natural Self-Learners

There's a common misconception that successful self-learners are inherently disciplined or naturally curious. In reality, self-directed learning is less about innate talent and more about cultivated habits, supportive environments, and emotional resilience. Many people who appear to learn effortlessly on their own have developed systems over time, often shaped by early educational experiences, mentorship, or structured routines.

For others, especially those without prior exposure to autonomous learning, the transition from formal instruction to independent study can feel overwhelming. Without clear guidance, feedback, or accountability, motivation quickly wanes. This doesn’t mean these individuals lack potential—it means the conditions for self-learning haven’t been met.

Common Psychological Barriers to Self-Learning

Internal resistance plays a significant role in limiting self-directed education. These mental blocks are often invisible but deeply impactful:

- Fear of failure: When there’s no external evaluation, the pressure to “get it right” can become paralyzing. The absence of grades or deadlines may increase anxiety rather than reduce it.

- Imposter syndrome: Many doubt their ability to learn complex topics without institutional validation. They question whether they’re “smart enough” or “qualified” to dive into new material.

- Lack of intrinsic motivation: Not everyone finds joy in acquiring knowledge for its own sake. If learning doesn’t serve an immediate purpose—like career advancement—it’s easy to deprioritize.

- Perfectionism: Some delay starting because they believe they must follow the “perfect” course, use the “best” resources, or master everything at once.

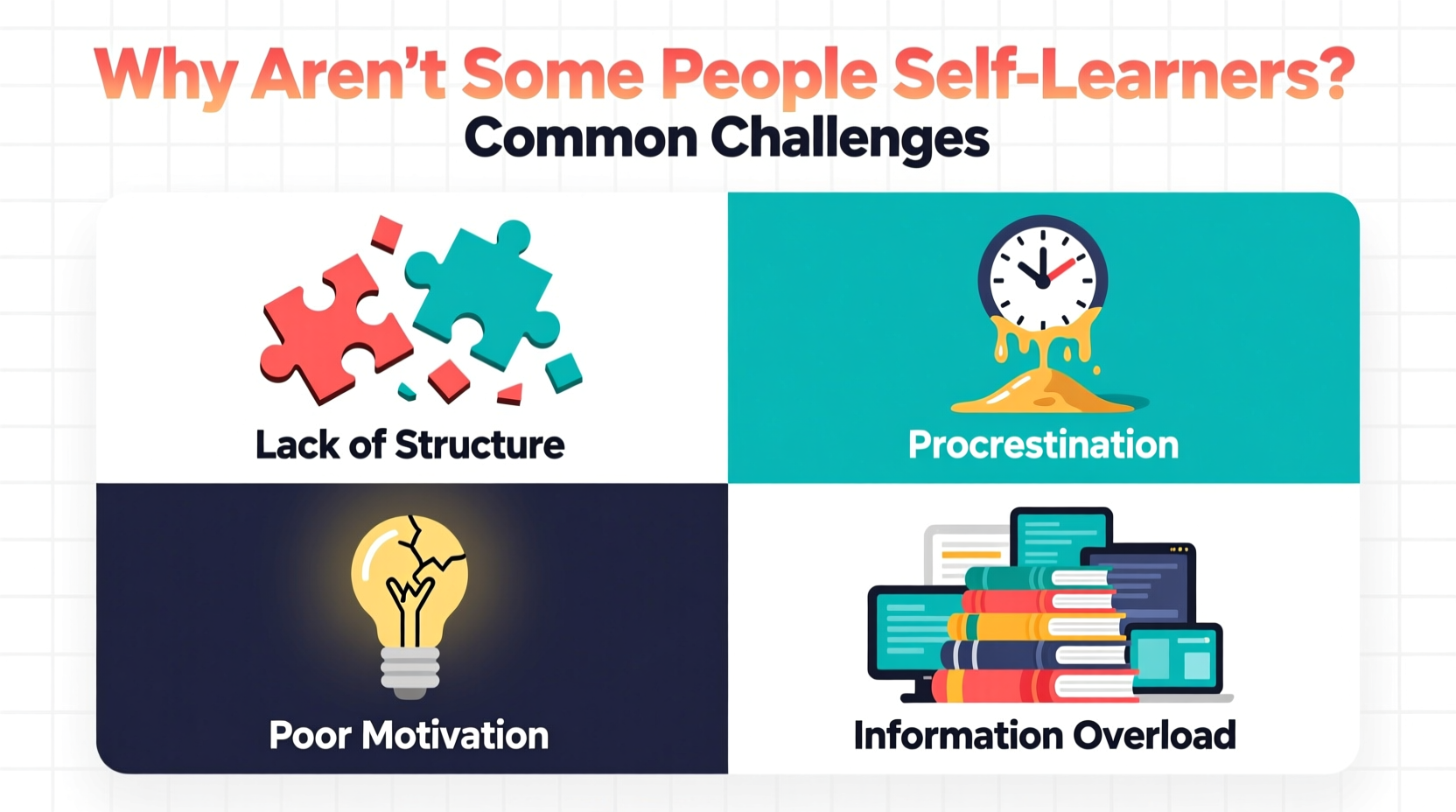

Environmental and Structural Challenges

Even the most motivated individual can falter when external conditions work against them. Several systemic factors hinder self-learning:

- Limited access to technology: Reliable internet, devices, and digital literacy are prerequisites for most modern learning platforms. Millions lack consistent access.

- Time poverty: People working multiple jobs, caring for family members, or managing health issues often don’t have surplus time to dedicate to unstructured learning.

- Poor learning environments: Noisy homes, shared spaces, or lack of privacy make focused study difficult.

- Overwhelming choice: The abundance of free courses, YouTube tutorials, and apps leads to decision fatigue. Without curation, learners freeze or jump between resources without progress.

“Autonomy in learning requires scaffolding. You can’t expect someone to climb without first building a ladder.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Educational Psychologist

Learning Styles and Cognitive Differences

Not all brains process information the same way. Traditional education systems favor auditory and reading/writing learners, leaving visual or kinesthetic learners behind. When transitioning to self-learning, these disparities intensify:

| Learning Style | Preferred Method | Common Self-Learning Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Auditory | Listening to lectures, podcasts | May skip hands-on practice needed for retention |

| Visual | Diagrams, videos, infographics | Struggles with text-heavy materials common in MOOCs |

| Kinesthetic | Hands-on experimentation, movement | Frustrated by passive video watching; needs physical engagement |

| Reading/Writing | Note-taking, articles, books | May avoid interactive tools like coding sandboxes or simulations |

When self-learners don’t recognize their preferred style, they may label themselves as “bad at learning,” when in fact, the method just doesn’t align with how their brain works best.

Mini Case Study: From Frustration to Fluency

James, a 34-year-old warehouse supervisor, wanted to learn web development to transition into tech. He downloaded coding apps, signed up for free bootcamps, and watched dozens of tutorials. After three months, he felt discouraged—he understood concepts in isolation but couldn’t build anything functional.

The turning point came when he joined a local community coding group. Through peer collaboration, project-based challenges, and weekly feedback, his confidence grew. What failed in isolation succeeded in community. James realized he wasn’t a poor self-learner—he was a social learner who thrived on interaction and real-time problem-solving.

His story illustrates a crucial insight: self-learning doesn’t have to mean solitary learning. Redefining independence to include guided autonomy made all the difference.

Step-by-Step Guide to Building Self-Learning Capacity

Becoming a self-learner is a skill, not a trait. It can be developed with intentional steps:

- Assess your current mindset: Journal about past learning experiences. Identify patterns of avoidance, frustration, or burnout.

- Define a clear, meaningful goal: Instead of “learn programming,” try “build a website for my side business in 8 weeks.” Specificity fuels commitment.

- Choose one high-quality resource: Avoid juggling five platforms. Pick one course, book, or mentor and stick with it for at least 30 days.

- Schedule micro-sessions: Block 25 minutes daily in your calendar. Use a timer. Consistency matters more than duration.

- Track progress publicly: Share updates with a friend, post on social media, or keep a visible checklist. External visibility increases accountability.

- Seek feedback early: Join forums, attend virtual office hours, or ask someone knowledgeable to review your work—even imperfect drafts.

- Reflect weekly: Every Sunday, answer: What worked? What didn’t? What will I adjust?

Checklist: Are You Set Up for Self-Learning Success?

- ✅ I have a specific reason for learning this topic

- ✅ I’ve identified at least one trusted resource

- ✅ I’ve blocked time in my schedule for regular study

- ✅ I know my preferred learning style (visual, auditory, etc.)

- ✅ I have a way to get feedback or ask questions

- ✅ I’ve told someone about my goal to increase accountability

- ✅ I’ve prepared a distraction-free space (even if temporary)

FAQ

Can anyone become a self-learner, or is it a natural ability?

Anyone can develop self-learning skills with practice and support. While some pick it up faster due to prior experience or personality traits, the behaviors—goal-setting, time management, reflection—are learnable by all.

How do I stay motivated when no one is checking my progress?

Create artificial accountability: share updates with a friend, join a study group, or use habit-tracking apps. Also, focus on small wins—each completed lesson is a victory worth acknowledging.

What if I start but lose interest after a few days?

This is normal. Re-evaluate your goal. Is it truly meaningful to you? Break it into smaller milestones. Sometimes re-engagement comes not from more discipline, but from better alignment with your values.

Conclusion

The inability to self-learn isn’t a personal failing—it’s often a signal that the right conditions aren’t in place. Whether it’s fear, lack of structure, unsuitable methods, or life circumstances, the barriers are real but surmountable. By addressing mindset, environment, and strategy, anyone can cultivate the ability to direct their own education.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?