Across ponds, lakes, and slow-moving streams, a common sight unfolds: tiny insects skimming effortlessly across the surface of the water as if defying gravity. Water striders, backswimmers, and even some beetles appear to glide on an invisible film, leaving ripples in their wake. This remarkable ability isn't magic—it's science. The phenomenon is rooted in a delicate balance of physical forces and biological adaptations that allow certain insects to exploit the unique properties of water. Understanding this reveals not only a fascinating aspect of nature but also inspires innovations in robotics and materials science.

The Role of Surface Tension

At the heart of this ability lies a fundamental property of liquids: surface tension. Water molecules are highly cohesive due to hydrogen bonding. Molecules within the bulk of the liquid are pulled equally in all directions by neighboring molecules, but those at the surface experience a net inward pull. This creates a \"skin\" or elastic-like layer at the air-water interface—surface tension.

This thin film is strong enough to support small objects that would otherwise sink. For insects, especially those with low body mass, surface tension provides a platform they can stand and move upon without breaking through. Think of it like a trampoline made of water molecules; light enough creatures can bounce or walk without rupturing the surface.

Physical Adaptations of Water-Walking Insects

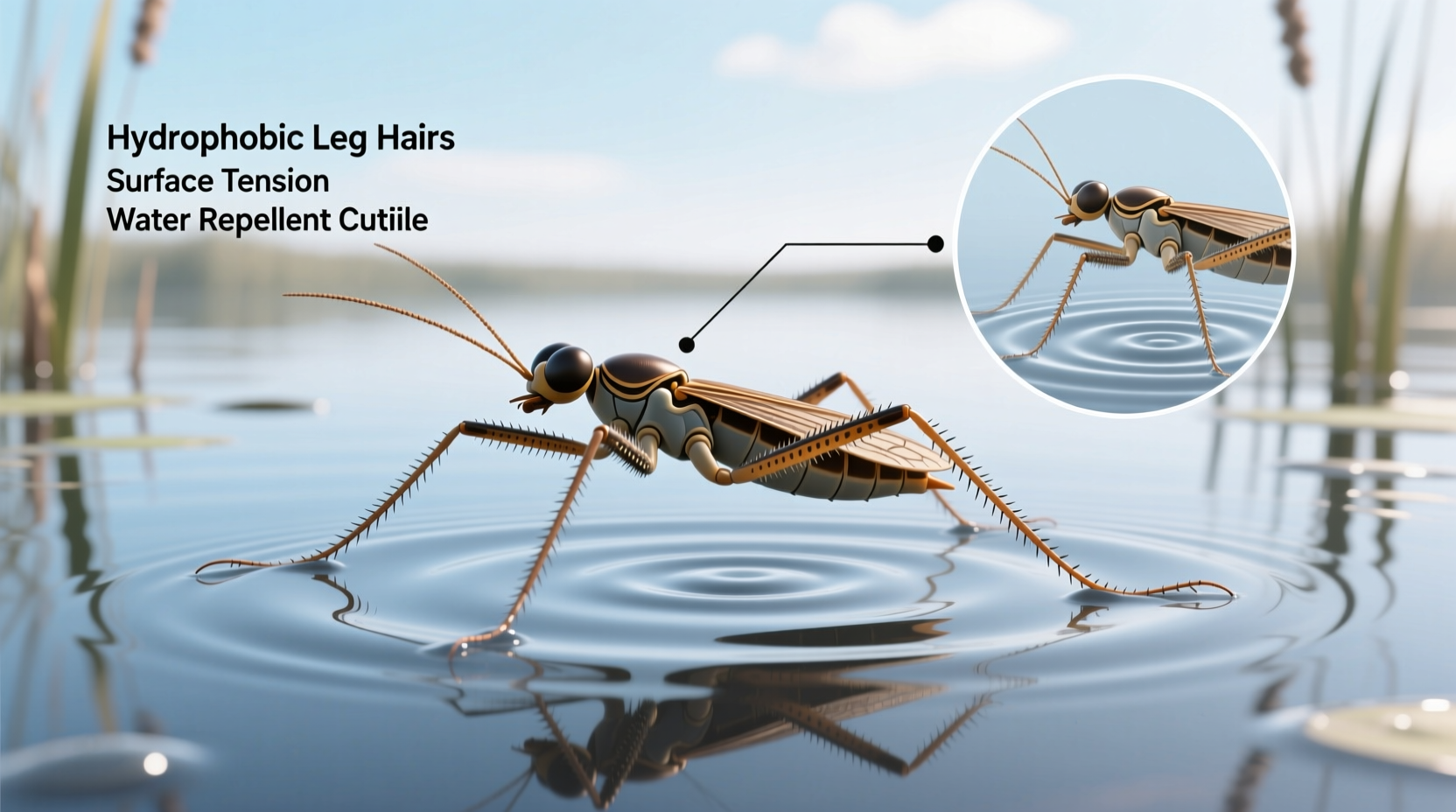

Nature has equipped certain insects with specialized anatomical features that maximize their interaction with surface tension while minimizing disruption. These adaptations go beyond mere weight management.

- Water-repellent (hydrophobic) legs: Many water-walking insects have legs covered in microscopic hairs that trap air, creating a cushion that prevents wetting. This hydrophobicity ensures the legs don’t penetrate the water surface.

- Long, slender legs: Species like the water strider (Gerridae family) have elongated middle and hind legs that distribute their weight over a larger surface area, reducing pressure on any single point.

- Optimal body mass: Most of these insects weigh less than 10 milligrams, allowing them to stay above the critical threshold where surface tension fails.

These traits combine to form what scientists call a \"non-wetting interface\"—a condition where the insect interacts with water without becoming submerged.

How Hydrophobic Hairs Work at the Microscopic Level

The secret lies in microstructures. Under a microscope, the legs of a water strider reveal thousands of tiny, groove-lined hairs called microsetae. These structures trap air and reduce contact angle hysteresis, meaning water droplets roll off easily rather than adhering.

Researchers at MIT studying biomimetic materials have replicated this design using nanofabricated surfaces that mimic insect leg textures. Such surfaces could lead to waterproof coatings for ships or medical devices.

“Evolution has optimized these insects to operate at the very edge of physical possibility—where biology meets fluid mechanics.” — Dr. John Bush, Professor of Applied Mathematics, MIT

Physics of Locomotion: How Do They Move?

Walking on water isn’t just about staying afloat—it’s about propulsion. Unlike swimming, which relies on pushing against water beneath, surface-dwelling insects use capillary waves and vortices to move forward.

When a water strider rows its legs, it creates tiny dimples in the surface. As the leg pushes backward, it generates swirling vortices just below the surface. These vortices transfer momentum to the water, propelling the insect forward without breaking the surface film.

Interestingly, juvenile water striders cannot generate waves efficiently due to their shorter legs. Instead, they rely entirely on viscous forces—essentially “paddling” through the high-resistance boundary layer near the surface.

Step-by-Step Guide: How a Water Strider Moves Across Water

- The insect positions its long middle legs slightly behind its center of mass.

- It presses down gently, deforming the water surface into a U-shaped dimple.

- As it sweeps the legs backward, it creates subsurface vortices that push water rearward.

- Newton’s third law applies: the reaction force moves the insect forward.

- The hydrophobic legs slide out of the dimple without resistance, ready for the next stroke.

- Front legs guide direction; hind legs stabilize and assist in steering.

Limitations and Environmental Factors

While impressive, this ability has limits. Several environmental conditions can disrupt an insect’s capacity to walk on water:

| Factor | Effect on Water-Walking Ability | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Rain or splashing | Disrupts surface integrity | Droplets break surface tension locally, causing instability. |

| Pollution (oils, detergents) | Reduces surface tension | Surfactants weaken molecular cohesion, making the surface too weak to support weight. |

| Wind | Creates ripples and turbulence | Makes it harder to maintain balance and generate efficient strokes. |

| High humidity | Minimal impact | Affects evaporation rate but not surface mechanics directly. |

Mini Case Study: The Water Strider’s Hunting Strategy

In a quiet pond in rural Japan, a water strider detects faint vibrations across the surface. A mosquito larva has surfaced nearby, unaware of the predator gliding silently toward it. Using its sensitive front legs as mechanoreceptors, the strider analyzes the ripple pattern to determine distance and direction.

In less than a second, it executes three rapid strokes, covering 40 times its body length per second. Its legs never pierce the surface. It captures the prey with precision, demonstrating not just locomotion mastery but also ecological advantage derived from surface walking.

This behavior highlights how evolution has turned a physical constraint—the inability to swim effectively—into a predatory strength.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can all insects walk on water?

No. Only specific species adapted to aquatic surface environments can do so. Most insects either sink, swim, or fly. Common examples include water striders, broad-backed bugs, and some springtails.

Do these insects ever fall in?

Yes, especially during storms or if contaminated by pollutants. Once wetted, their hydrophobic coating may fail, increasing the risk of drowning. Some can swim briefly, but prolonged submersion is often fatal.

Is surface tension the only force involved?

No. While surface tension is primary, buoyancy, viscosity, and capillary action also play roles. At very small scales, viscous forces dominate over inertial ones, changing how movement works compared to larger animals.

Biomimicry and Technological Applications

The study of water-walking insects has inspired engineers to develop robots capable of similar feats. Known as “water-walking microrobots,” these devices use lightweight frames and hydrophobic coatings to traverse liquid surfaces for environmental monitoring or search-and-rescue missions.

In one project at Carnegie Mellon University, researchers built a palm-sized robot modeled after the water strider. By mimicking leg motion and material properties, it achieved propulsion without breaking the surface—proof that nature continues to inform cutting-edge technology.

Conclusion: Nature’s Mastery of Physics

The ability of insects to walk on water is a stunning example of evolutionary ingenuity meeting the laws of physics. From microscopic hairs to precise leg movements, every detail is fine-tuned to exploit surface tension. This phenomenon reminds us that even the smallest creatures operate under complex scientific principles—and that observing nature closely can yield profound insights.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?