For centuries, humans have gazed at the Moon and noticed something peculiar: its face never changes. The same craters, maria, and highlands appear night after night, regardless of season or location on Earth. It’s not a trick of perception—Earth observers truly only ever see one hemisphere of the Moon. This phenomenon, while seemingly mysterious, is grounded in well-understood celestial mechanics. The answer lies in a process called tidal locking, a gravitational dance that has unfolded over billions of years between Earth and its natural satellite.

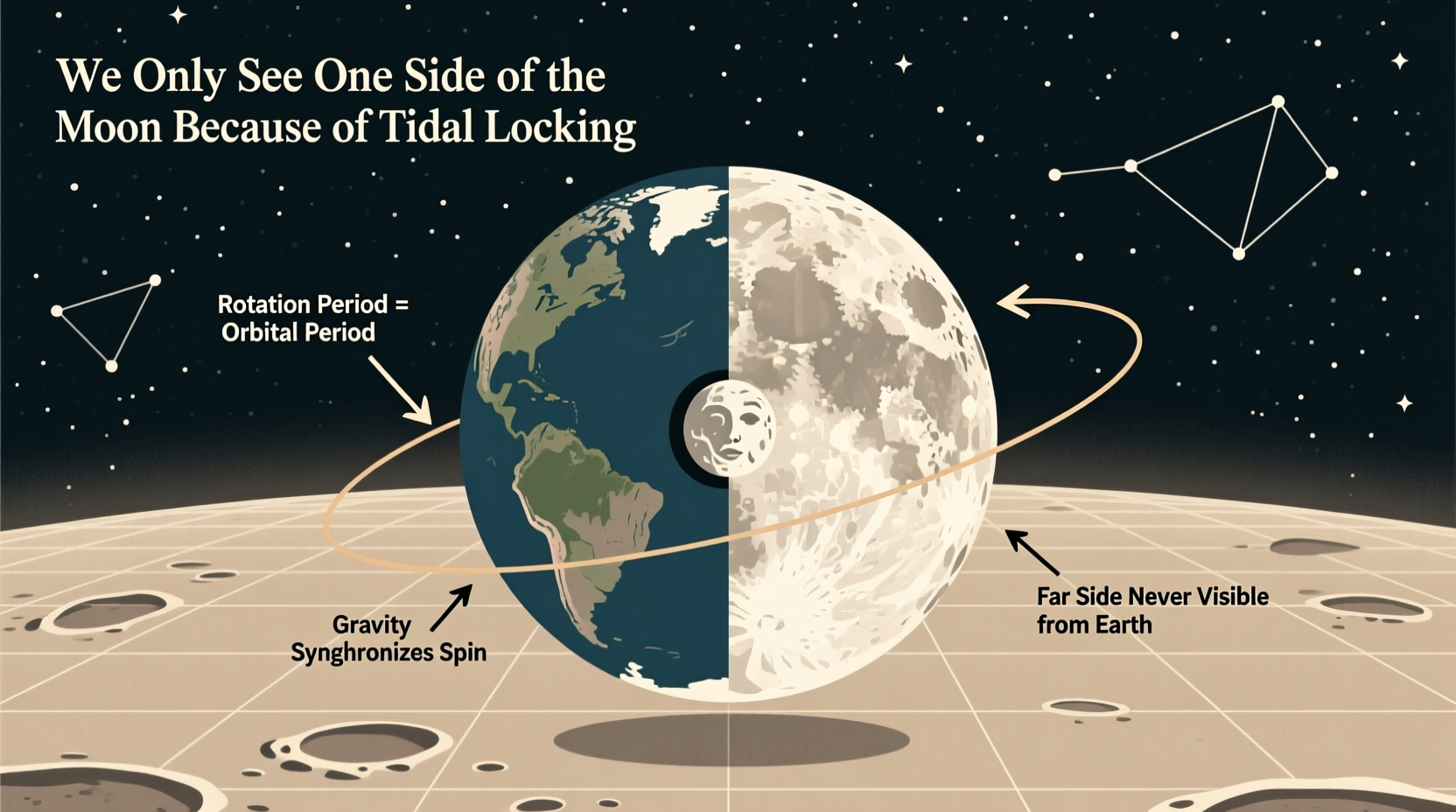

The Moon completes one full rotation on its axis in the same time it takes to orbit Earth—about 27.3 days. This synchrony ensures that the same lunar hemisphere always faces our planet. But how did this happen? And what does it mean for our understanding of planetary systems? Let’s explore the science behind this enduring cosmic alignment.

Tidal Locking: The Gravitational Synchronization

Tidal locking occurs when the gravitational forces between two orbiting bodies cause their rotational periods to match their orbital periods. In the case of the Earth-Moon system, Earth’s gravity exerted uneven pulls on the early Moon, which was rotating faster than it does today. Over time, these differential forces created internal friction within the Moon, gradually slowing its rotation until it matched its orbital period.

This process is not unique to our Moon. Most large moons in the solar system are tidally locked to their parent planets. For example, Jupiter’s four largest moons—Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto—are all tidally locked. Even Pluto and its largest moon Charon are mutually tidally locked, meaning each always shows the same face to the other.

The Role of Gravity and Tidal Bulges

To understand tidal locking more deeply, consider the concept of tidal bulges. Earth’s gravity pulls more strongly on the near side of the Moon than the far side, creating a slight elongation—a bulge—along the Earth-Moon axis. When the Moon rotated faster in the past, this bulge wasn’t perfectly aligned with Earth. The gravitational pull on the offset bulge acted like a brake, sapping rotational energy and slowing the Moon’s spin.

Eventually, the rotation slowed enough that the bulge remained permanently aligned with Earth. At this point, no further braking occurred, and the Moon became tidally locked. This state is stable and self-correcting; any small deviation would be corrected by gravitational torque.

Interestingly, Earth is also undergoing a similar process, though much more slowly. The Moon’s gravity creates tidal bulges in Earth’s oceans (and even its crust), and because Earth rotates faster than the Moon orbits, these bulges lead slightly ahead of the Moon. This transfers angular momentum from Earth to the Moon, causing Earth’s rotation to slow down and the Moon to recede from Earth at about 3.8 centimeters per year.

Libration: Why We Actually See Slightly More Than Half

While we often say we only see one side of the Moon, that’s not entirely accurate. Due to a phenomenon called libration, observers on Earth can actually see about 59% of the lunar surface over time. Libration arises from three main factors:

- Orbital eccentricity: The Moon’s orbit is not perfectly circular. As it moves faster at perigee (closest to Earth) and slower at apogee (farthest), its rotation sometimes leads or lags its orbital position, revealing parts of the eastern and western limbs.

- Axial tilt: The Moon’s rotational axis is slightly inclined relative to its orbital plane around Earth, allowing us to “peek” over the north and south poles at different points in its orbit.

- Daily parallax: Observers on Earth’s surface view the Moon from slightly different angles as Earth rotates, enabling glimpses around the edges.

These subtle oscillations allow astronomers and amateur skywatchers to observe features just beyond the average lunar limb, especially during favorable viewing conditions.

Historical Discovery and Exploration

The far side of the Moon remained completely unknown until the Space Age. In 1959, the Soviet spacecraft Luna 3 captured the first grainy images of the lunar far side, revealing a dramatically different landscape—more rugged, heavily cratered, and lacking the vast dark plains (maria) so prominent on the near side.

“The far side of the Moon is unlike anything we expected—no seas, just mountains and craters as far as the eye can see.” — Boris Vasin, Soviet space engineer commenting on Luna 3 imagery

Since then, numerous missions—including NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and China’s Chang’e 4, which landed on the far side in 2019—have mapped and studied this hidden hemisphere. Scientists now believe the asymmetry between the two sides stems from differences in crustal thickness and ancient geological processes influenced by Earth’s proximity during the Moon’s formation.

What the Far Side Reveals About Lunar Origins

One leading theory for the Moon’s origin is the giant impact hypothesis: a Mars-sized body collided with early Earth, ejecting debris that coalesced into the Moon. Because the young Moon formed close to Earth, the near side cooled more slowly due to radiant heat from Earth, allowing denser minerals to sink and lighter ones (like plagioclase) to rise. This may explain why the near side has a thinner crust and more volcanic activity (leading to maria), while the far side retained a thicker crust and fewer lava flows.

The far side is also an ideal location for radio astronomy. Shielded from Earth’s constant radio noise, it offers a pristine environment for observing low-frequency signals from the early universe. Future lunar observatories may take advantage of this quiet zone to peer into the cosmic dark ages before the first stars formed.

Do's and Don'ts of Understanding the Moon's Rotation

| Do | Don't |

|---|---|

| Remember that the Moon rotates—it just matches its orbital period | Assume the Moon doesn’t rotate at all |

| Consider libration when observing the Moon through a telescope | Expect to see the exact same features every night without variation |

| Use binoculars or a small telescope to notice subtle edge details | Believe the far side is perpetually dark (\"dark side\") |

| Learn about tidal forces shaping planetary systems | Think tidal locking is rare or unnatural |

FAQ

Does the far side of the Moon ever get sunlight?

Yes. The far side receives just as much sunlight as the near side. The misconception that it’s the \"dark side\" comes from confusion with \"unknown side.\" Each lunar hemisphere experiences about 14 days of daylight followed by 14 days of night during the Moon’s monthly cycle.

Could the Moon ever show us its other side?

No—not unless a major external force disrupts the current tidal equilibrium. The Earth-Moon system is gravitationally stable, and the lock is self-sustaining. Even significant impacts wouldn’t permanently alter the synchronization.

Will Earth ever become tidally locked to the Moon?

In theory, yes—but not for tens of billions of years. If the Sun didn’t expand into a red giant and destroy both bodies first, Earth’s rotation would eventually slow to match the Moon’s orbital period. At that point, the Moon would appear stationary in the sky, and only one side of Earth would see it.

Step-by-Step: Observing Lunar Libration

- Choose a clear night and use binoculars or a small telescope.

- Locate the Moon and sketch or photograph its visible features, noting the terminator (day-night line).

- Repeat observations weekly over a month, focusing on the edges (limbs).

- Compare your records—you’ll notice slight shifts in visibility near the poles and along the eastern and western edges.

- Consult a lunar libration chart online to correlate your observations with predicted wobbles.

Conclusion

The fact that we only see one side of the Moon is not a coincidence but a direct result of gravitational physics in action. Tidal locking exemplifies how celestial bodies influence each other over vast timescales, shaping their rotations, orbits, and even geologies. Understanding this process deepens our appreciation of the Moon not just as a nighttime companion, but as a dynamic world shaped by its relationship with Earth.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?