Cells are the fundamental units of life, but despite their incredible complexity, they remain remarkably small. Most animal and plant cells range between 10 and 30 micrometers in diameter—so tiny that hundreds could fit on the head of a pin. This raises a compelling question: why haven’t evolution or biology produced giant cells capable of more functions or greater efficiency? The answer lies not in imagination, but in physics, chemistry, and geometry. There are strict biophysical constraints that prevent cells from growing indefinitely. Understanding these limitations reveals how life balances function, structure, and survival at microscopic scales.

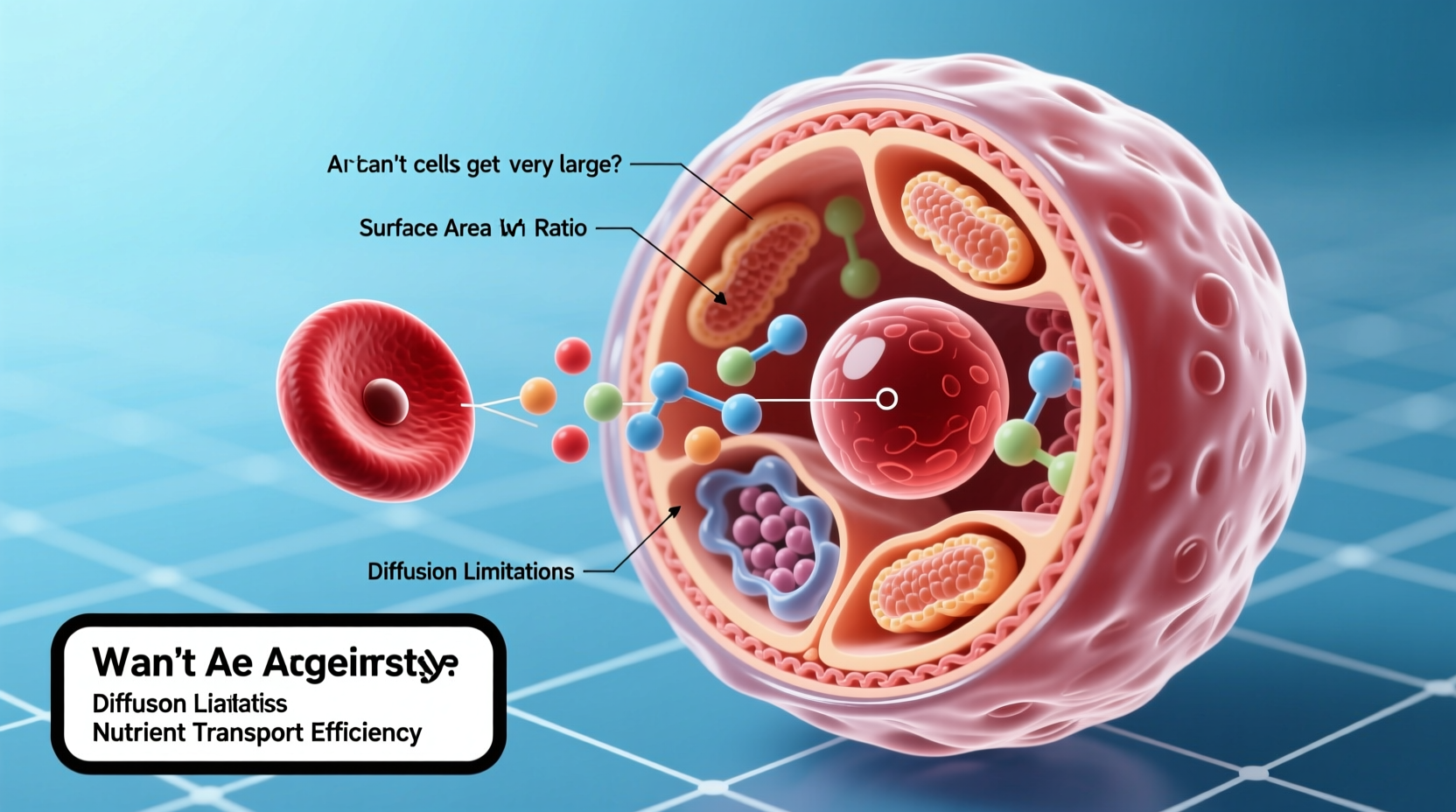

The Surface Area to Volume Ratio Problem

One of the most critical factors limiting cell size is the relationship between surface area and volume. As a cell grows, its volume increases faster than its surface area. This imbalance creates a bottleneck for essential processes like nutrient uptake, waste removal, and gas exchange—all of which depend on the cell membrane (the surface).

Consider a spherical cell. Its surface area grows with the square of the radius (4πr²), while its volume increases with the cube (⁴⁄₃πr³). When the radius doubles, surface area quadruples, but volume increases eightfold. That means each unit of surface must now service twice as much internal volume. Eventually, the membrane becomes insufficient to support the metabolic demands of the cytoplasm.

This geometric constraint forces cells to stay small or adapt structurally—such as by folding membranes or elongating shapes—to maximize surface exposure relative to volume.

DNA Overload and Gene Expression Limits

Another key limitation is genetic control. A typical eukaryotic cell contains only one or two copies of its genome. All proteins, enzymes, and regulatory molecules are produced based on instructions from this central DNA library. As a cell grows larger, the demand for gene products increases proportionally with volume—but the number of DNA templates does not.

The nucleus becomes a bottleneck. It can only transcribe so many mRNA strands at once. If the cell were to double in linear size, its volume would increase eightfold, requiring roughly eight times more proteins—but the nucleus still has the same amount of DNA. Without additional genomes, the cell cannot keep up with protein synthesis demands, leading to functional insufficiency.

“The nucleus acts like a factory’s instruction hub. No matter how large the production floor gets, if you don’t add more blueprints, output stalls.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Molecular Biologist, University of Edinburgh

Some organisms circumvent this through polyploidy—having multiple copies of chromosomes—but even this has limits and is typically seen in specialized cells like liver hepatocytes or certain plant cells.

Intracellular Transport Efficiency Declines with Size

Inside the cell, materials move via diffusion or active transport along the cytoskeleton. Diffusion works well over short distances—on the order of micrometers—but slows dramatically over longer ones. In a hypothetical giant cell measuring hundreds of microns across, it could take minutes for a molecule to drift from the membrane to the nucleus.

Metabolism requires speed and precision. Delayed delivery of ATP, ions, or signaling molecules disrupts homeostasis. For example, calcium signals used in muscle contraction or neurotransmitter release rely on rapid ion movement. In oversized cells, such responses would be dangerously sluggish.

To compensate, some large cells evolve mechanisms like internal streaming (cyclosis) or distribute organelles strategically. The amoeba *Chaos carolinense*, which can reach 1 mm in length, uses vigorous cytoplasmic flow to mix contents. But these adaptations are energetically costly and rare.

Structural Integrity and Mechanical Stress

As cells grow, physical forces become harder to manage. The plasma membrane must withstand osmotic pressure, especially in hypotonic environments where water enters by osmosis. Larger cells have greater internal volume pushing outward, increasing tension on the membrane. Without rigid walls (like in plants or bacteria), animal cells risk bursting.

Even with structural supports like the cytoskeleton, maintaining shape and resisting deformation becomes more difficult at larger sizes. Microtubules and actin filaments can only provide so much reinforcement before buckling under stress. This mechanical fragility further constrains maximum viable cell dimensions.

Case Study: The Ostrich Egg – An Exception That Proves the Rule

The largest known single cell is the ostrich egg, specifically the yolk, which can measure over 8 centimeters in diameter. At first glance, this seems to defy the rules of cell size. However, the egg cell is metabolically quiescent—it doesn’t perform active respiration or division until fertilization begins.

Moreover, most of the volume is inert nutrient storage (yolk), not metabolically active cytoplasm. The actual living portion—the germinal disc—is tiny, about the size of a pinhead. Thus, the functional cell remains small; the rest is cargo. This illustrates a crucial principle: large cells avoid size limitations by minimizing active volume or entering dormant states.

| Cell Type | Average Size (μm) | Special Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Human red blood cell | 7–8 | Biconcave shape maximizes surface area |

| Liver hepatocyte | 20–30 | Polyploid nuclei support high metabolism |

| Frog oocyte | 1,000–1,200 | Yolk-rich, low metabolic rate |

| Ostrich egg (yolk) | ~80,000 | Dormant; nutrients stored passively |

| Neurospora crassa hyphae | up to 500,000 (length) | Tube-like; nuclei distributed throughout |

Strategies Cells Use to Stay Functional at Larger Sizes

While true unicellular giants are rare, some cells push the boundaries using clever workarounds:

- Multinucleate structure: Muscle fibers and fungal hyphae contain multiple nuclei, distributing genetic workload.

- Flattened or elongated shape: Nerve cells stretch meters long but remain ultra-thin, preserving favorable surface-to-volume ratios.

- Internal compartmentalization: Organelles localize reactions and reduce diffusion distances.

- Cytoplasmic streaming: Movement within the cell enhances mixing and transport.

Checklist: Key Factors Limiting Cell Size

- Surface area cannot keep up with increasing volume → inefficient exchange

- DNA cannot produce enough RNA/proteins for large cytoplasmic demands

- Diffusion becomes too slow for timely intracellular communication

- Mechanical stress risks membrane rupture or structural collapse

- Energy distribution becomes uneven across large distances

- Waste accumulation occurs in poorly circulated regions

FAQ

Can cells divide to stay small?

Yes—cell division resets size by splitting volume between two daughter cells. This restores optimal surface-to-volume ratios and ensures each new cell receives sufficient genetic material.

Are there any truly giant active cells?

Few. Some algae like Acetabularia grow several centimeters tall but remain narrow. They maintain viability through efficient cytoplasmic streaming and a single, large nucleus adapted for extensive transcription.

Why don’t neurons face the same size issues?

Neurons are long but extremely thin—often less than 1 micron in diameter outside the soma. Their axons minimize volume, allowing diffusion and transport systems to function effectively over distance.

Conclusion: Scaling Life Within Physical Laws

The reason cells can’t get very big isn’t due to a lack of evolutionary ambition—it’s governed by immutable laws of physics and biochemistry. From surface constraints to DNA capacity, every aspect of cellular function degrades when scaled beyond a certain point. Nature’s solution? Not bigness, but complexity through multicellularity. Instead of building one enormous super-cell, organisms evolved trillions of small, specialized units working in concert.

This insight underscores a deeper truth: life thrives not by defying limits, but by innovating within them. By staying small, cells achieve efficiency, resilience, and adaptability—qualities that make complex life possible.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?