Singing is a universal form of expression, yet many people believe they \"can't carry a tune.\" This perception raises an important question: Is singing ability purely innate, or can anyone learn to sing with enough practice? The answer lies at the intersection of neuroscience, physiology, psychology, and education. While nearly all humans possess the physical apparatus for singing, individual differences in pitch perception, motor control, and confidence shape vocal performance. Understanding the science behind singing reveals that most people aren’t “tone-deaf”—they simply haven’t learned how to connect their ears to their voices effectively.

The Anatomy of Singing: What It Takes to Produce Music

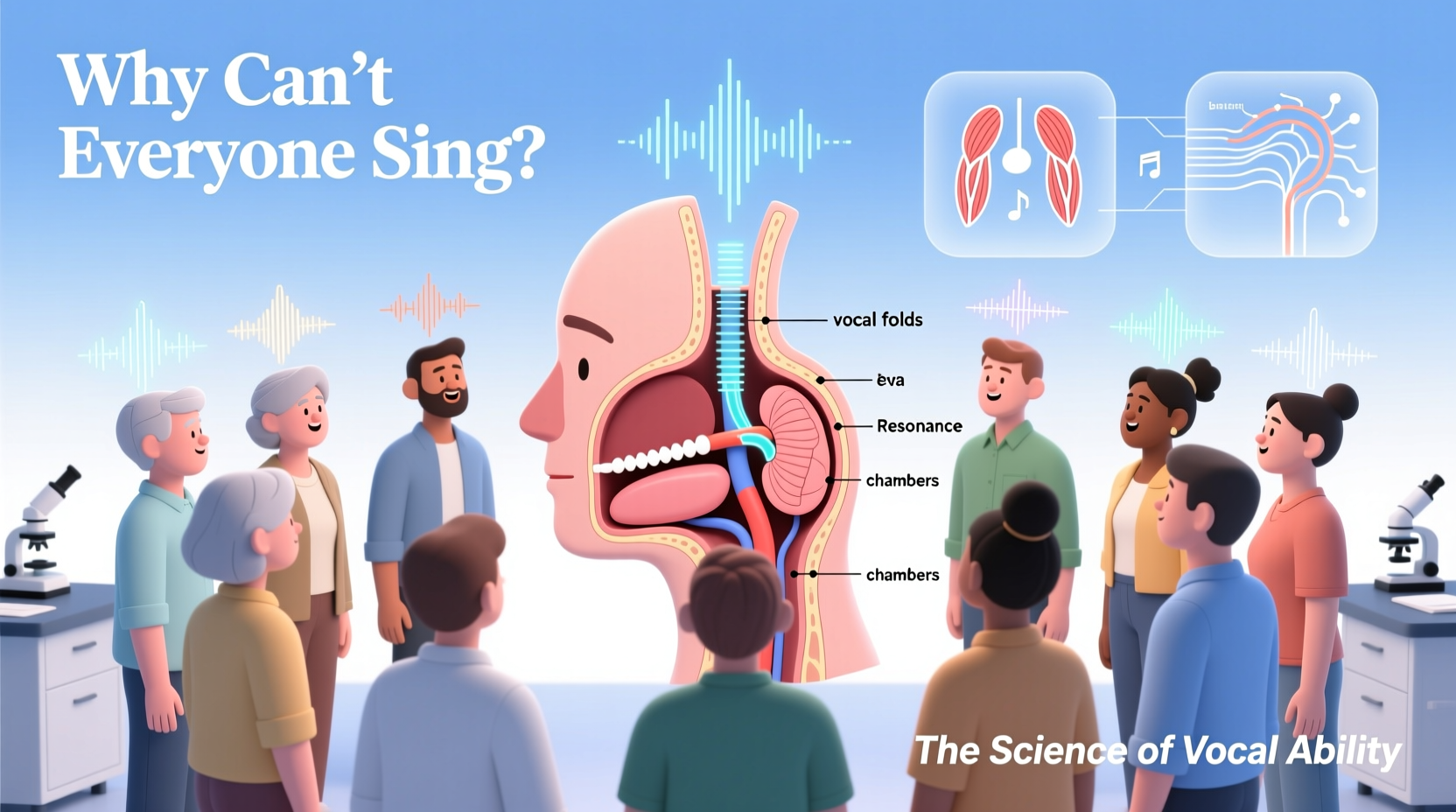

Singing is a complex coordination of multiple body systems. At its core, it involves three key components: respiration, phonation, and resonance. Air from the lungs passes through the trachea and causes the vocal folds in the larynx to vibrate, producing sound. This raw tone is then shaped by the throat, mouth, and nasal cavities into recognizable pitches and words.

However, producing a note is only half the battle. Accurate singing requires precise neural feedback loops. The brain must compare the intended pitch (based on internal musical imagination) with the actual sound produced (heard via bone conduction and external hearing). When there's a mismatch, corrections must be made in real time—a process known as auditory-motor integration.

“Singing isn’t just about the voice—it’s about the brain’s ability to translate sound into muscular action.” — Dr. Simone Dalla Bella, Cognitive Neuroscientist, Center for Research on Brain, Music, and Language

Why Some People Struggle: The Science Behind Poor Pitch Singing

Research shows that fewer than 4% of the population suffers from congenital amusia—true “tone deafness,” where individuals cannot distinguish between different pitches. For the vast majority of self-described “bad singers,” the issue isn’t hearing but the connection between auditory perception and vocal production.

A 2005 study by researchers at University College London found that poor pitch singers could often detect when a note was off-key but were unable to adjust their own vocal output accordingly. This disconnect suggests a deficit in sensorimotor mapping rather than hearing impairment.

- Pitch Matching Deficits: Many struggle to reproduce a heard pitch accurately due to weak neural pathways between the auditory cortex and motor areas controlling the larynx.

- Vocal Control Limitations: Inexperienced singers may lack fine control over breath support, laryngeal tension, and vowel shaping, leading to inconsistent pitch and tone.

- Lack of Early Exposure: Children who grow up in environments with limited musical engagement may miss critical developmental windows for refining pitch accuracy.

Can Anyone Learn to Sing? The Role of Training and Neuroplasticity

The human brain is remarkably adaptable. Through deliberate practice, most individuals can improve their singing ability significantly—a phenomenon supported by neuroplasticity, the brain’s capacity to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections.

Studies using functional MRI have shown that after just six weeks of weekly vocal lessons, participants exhibit increased activity in brain regions associated with pitch processing and motor planning. These changes correlate directly with improved pitch accuracy and vocal control.

Learning to sing follows a progression similar to acquiring any skilled movement—like riding a bike or typing. Beginners rely heavily on conscious effort and external feedback. With repetition, these actions become automatic and intuitive.

Key Factors That Influence Singing Development

| Factor | Impact on Singing Ability | Modifiable? |

|---|---|---|

| Hearing Sensitivity | Essential for pitch detection; rare deficits are permanent | Largely fixed, but training improves discrimination |

| Vocal Fold Structure | Affects timbre and range; minor anatomical variations common | Inherent, but technique compensates |

| Auditory-Motor Integration | Crucial for matching heard pitch to vocal output | Highly trainable |

| Musical Exposure | Early exposure strengthens pitch memory and rhythm sense | Can be developed at any age |

| Confidence & Anxiety | Fear of judgment inhibits vocal experimentation | Manageable through supportive environments |

Step-by-Step Guide to Developing Singing Skills

Improvement doesn’t require innate talent—just consistent, structured effort. Here’s a practical roadmap for building vocal competence:

- Assess Your Starting Point: Record yourself singing a simple melody like “Happy Birthday.” Listen critically: Are you consistently sharp, flat, or erratic?

- Train Your Ear: Use apps or online tools to practice interval recognition. Start with major seconds and fifths—the building blocks of melody.

- Match Pitch with Sirens: Glide your voice up and down like a siren, attempting to follow a reference tone from a piano or tuning app.

- Practice Short Melodic Patterns: Sing short 3-note sequences played on a keyboard. Repeat until you can match each note within 20 cents (a fraction of a semitone).

- Engage a Teacher: A trained vocal coach provides real-time feedback and corrects subtle issues in posture, breathing, and articulation.

- Sing Regularly in Context: Join a choir, karaoke group, or community class to normalize singing in front of others and reinforce learning.

Real Example: From Tone-Averse to Confident Singer

Mark, a 38-year-old accountant, avoided singing his entire life. He believed he was “musically hopeless” after being asked to stand silent during a school choir performance. Decades later, he joined a beginner’s adult singing workshop out of curiosity. Over 12 weeks, he practiced daily ear-training exercises and worked on matching pitches with guided vocal warm-ups.

By week eight, Mark could accurately reproduce simple melodies. His confidence grew, and he began singing along to songs in the car. After six months, he performed a solo verse at a friend’s birthday gathering—something he once thought impossible. His journey wasn’t about unlocking hidden talent; it was about rewiring his brain through persistence and targeted feedback.

Common Myths About Singing Debunked

- Myth: You’re either born with a good voice or you’re not.

Truth: While vocal timbre has genetic components, pitch accuracy and expression are skills refined through practice. - Myth: If you can’t sing now, you never will.

Truth: Adult brains retain plasticity. Late starters often succeed with structured training. - Myth: Singing teachers only help advanced performers.

Truth: Beginners benefit most—early guidance prevents bad habits and accelerates progress.

FAQ

Is it possible to be completely tone-deaf?

True clinical tone-deafness (amusia) affects roughly 1–4% of people. Most who think they’re tone-deaf actually have underdeveloped pitch-matching skills, not a hearing disorder. With training, even many with amusia can improve their singing accuracy.

How long does it take to learn to sing in tune?

Basic pitch-matching can be achieved in 3–6 months with consistent practice (15–20 minutes daily). Mastery takes longer, but noticeable improvement typically occurs within weeks.

Do I need to read music to learn to sing?

No. While reading music enhances understanding, many successful singers learn by ear. Focus first on listening, imitation, and vocal control—notation can come later.

Checklist: Building Foundational Singing Skills

- ✅ Test your pitch accuracy with a recording

- ✅ Practice matching single notes using a piano or app

- ✅ Perform daily humming or sirens across your comfortable range

- ✅ Train your ear with interval identification exercises

- ✅ Seek feedback from a teacher or trusted listener

- ✅ Sing in low-pressure settings (shower, car, private space)

- ✅ Track progress monthly with audio recordings

Conclusion

The belief that “not everyone can sing” is more myth than fact. Nearly all individuals possess the physiological and neurological potential to sing in tune. The gap between “bad” and “good” singers is rarely biological—it’s educational. With accurate feedback, consistent practice, and a willingness to engage, most people can learn to sing confidently and musically. The voice is an instrument shaped by experience, not destiny. Whether you dream of performing on stage or simply want to enjoy singing without fear, the path begins with one simple step: open your mouth and try.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?