It’s a common experience: after eating corn on the cob or a bowl of sweetcorn, you notice bright yellow kernels in your stool hours or days later. While this sight can be surprising—or even alarming—it’s completely normal. The human digestive system processes most foods into absorbable nutrients, but corn is one food that often passes through with its structure intact. This phenomenon isn’t a sign of poor digestion; it’s a result of biology, chemistry, and the unique makeup of corn itself.

Understanding why corn resists full digestion sheds light not only on how our bodies work but also on the role of dietary fiber, enzyme limitations, and the importance of chewing. This article explores the science behind undigested corn, explains what happens during digestion, and offers practical advice for maximizing nutrient absorption from fibrous foods.

The Structure of Corn: Why It Resists Breakdown

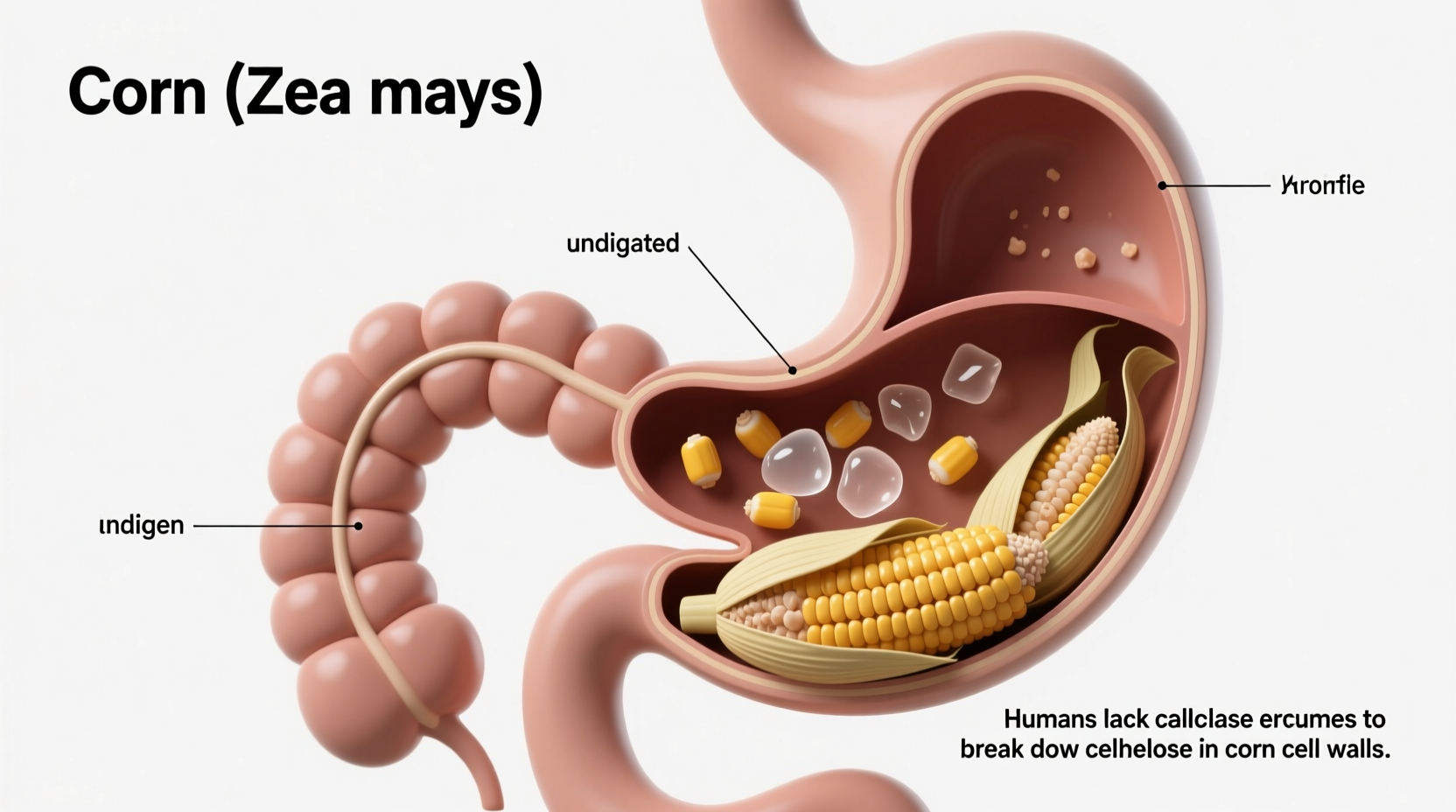

Corn, specifically the edible kernel known as the endosperm, is encased in a tough outer layer made primarily of cellulose. Cellulose is a complex carbohydrate and a key component of plant cell walls. While humans can digest starches and sugars found inside the kernel, we lack the necessary enzyme—cellulase—to break down cellulose.

This biological limitation means that while digestive enzymes like amylase (in saliva) and proteases (in the stomach and small intestine) can access some internal nutrients, the rigid hull remains largely untouched. As a result, whole or partially chewed kernels move through the gastrointestinal tract with their shape and color preserved.

Cellulose and the Human Digestive System

Unlike ruminants such as cows or sheep, which host symbiotic bacteria in their multi-chambered stomachs capable of fermenting cellulose, humans do not produce cellulase nor harbor enough cellulose-digesting microbes in the gut to break it down efficiently. The human large intestine contains bacteria that ferment certain types of fiber, but they are not effective against the dense, crystalline structure of corn cellulose.

Instead, cellulose acts as insoluble fiber, adding bulk to stool and promoting regular bowel movements. Though indigestible, it plays a beneficial role in gut health by supporting motility and preventing constipation.

Digestion Timeline: What Happens When You Eat Corn?

When corn enters the digestive tract, it undergoes the same mechanical and chemical processes as other foods—but with notable limitations due to its physical structure.

- Mouth: Chewing breaks kernels apart, exposing inner starches to salivary amylase. However, if kernels aren’t chewed well, much of the interior remains inaccessible.

- Stomach: Acid and churning further separate components, but the cellulose hull remains resistant to gastric juices.

- Small Intestine: Enzymes from the pancreas continue breaking down available carbohydrates and proteins. Nutrients like glucose and amino acids are absorbed here.

- Large Intestine: Water is reabsorbed, and gut bacteria ferment soluble fibers. Insoluble corn hulls pass through unchanged.

- Elimination: Undigested corn appears in stool typically 24–48 hours after consumption.

Nutrient Availability in Corn: Are You Missing Out?

Despite the visible passage of whole kernels, you're still absorbing valuable nutrients from corn. Inside each kernel lies starch, protein, vitamins (like B6 and folate), and antioxidants such as lutein and zeaxanthin. These become accessible only when the cellulose barrier is compromised—usually through thorough chewing or cooking methods that soften the hull.

Research shows that processing techniques like nixtamalization (used in making masa for tortillas), grinding, or prolonged cooking improve nutrient bioavailability by weakening the cell wall structure. In fact, hominy—corn treated with an alkaline solution—has enhanced calcium and niacin absorption compared to raw kernels.

| Form of Corn | Digestibility Level | Nutrient Accessibility |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Kernels (raw or boiled) | Low | Moderate (if chewed well) |

| Creamed Corn | High | High (cells broken mechanically) |

| Cornmeal / Grits | High | High (grinding exposes contents) |

| Popcorn | Moderate | Medium (expanded but hull intact) |

Common Misconceptions About Undigested Food

Seeing recognizable food particles in stool often triggers concern, especially among individuals monitoring digestive health. However, finding corn in feces does not indicate malabsorption disorders like celiac disease or pancreatic insufficiency—unless accompanied by symptoms such as weight loss, chronic diarrhea, or abdominal pain.

In most cases, undigested corn is simply evidence of efficient peristalsis and healthy transit time. It reflects the natural limits of human digestion rather than dysfunction.

“Just because something comes out looking like it went in doesn’t mean your body didn’t extract nourishment from it.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Gastroenterologist at Boston Digestive Institute

When to Be Concerned

If undigested food is frequent across multiple food types—not just corn—and occurs alongside bloating, gas, fatigue, or changes in bowel habits, it may signal an underlying issue. Conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), or enzyme deficiencies could impair overall digestion.

However, isolated sightings of corn require no medical intervention. They’re a normal consequence of eating fibrous plant material with resilient cellular structures.

Practical Tips for Better Digestion of Fibrous Foods

While you can’t change your body’s inability to digest cellulose, you can optimize how much nutrition you derive from corn and similar high-fiber vegetables.

- Chew corn slowly and thoroughly until it reaches a mushy consistency.

- Cook corn longer to soften the hulls—simmering or grilling helps break down structural integrity.

- Choose processed forms like polenta, grits, or canned corn when seeking higher digestibility.

- Avoid eating large quantities of raw corn if you have sensitive digestion.

- Stay hydrated—fiber works best with adequate water intake to support smooth elimination.

Checklist: Maximizing Nutrient Absorption from Corn

- ✅ Chew each bite of corn at least 20 times.

- ✅ Cook corn using moist heat (boiling, steaming) for longer durations.

- ✅ Combine corn with a source of fat for improved nutrient uptake.

- ✅ Consider blending or mashing cooked corn to disrupt cell walls.

- ✅ Monitor overall digestion—if patterns change, consult a healthcare provider.

Real Example: A Patient’s Surprise Discovery

Mark, a 34-year-old teacher, once visited his doctor worried about “undigested food” in his stool after a weekend barbecue where he ate several ears of grilled corn. He described seeing bright yellow pieces and feared a serious digestive problem. After reviewing his diet and symptoms—none beyond occasional bloating—the physician reassured him that corn was simply passing through intact. The doctor explained the role of cellulose and suggested Mark try cutting kernels off the cob and sautéing them in olive oil to enhance digestibility. Within a week, Mark reported fewer visible remnants and felt more confident about his digestive health.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it normal to see corn in my poop?

Yes, it's perfectly normal. The outer shell of corn is made of cellulose, which humans cannot digest. Whole or partially chewed kernels often appear unchanged in stool.

Can undigested corn cause blockages or harm?

No, undigested corn does not cause intestinal blockages in healthy individuals. It moves through the digestive tract safely and contributes to regular bowel movements due to its fiber content.

Does cooking corn make it easier to digest?

Yes. Cooking softens the cellulose structure and makes internal nutrients more accessible. Methods like boiling, steaming, or roasting improve digestibility compared to eating raw corn.

Conclusion: Embrace the Kernel, Understand the Process

Not being able to fully digest corn isn’t a flaw—it’s a reflection of human biology working as intended. Our digestive system evolved to extract energy and nutrients efficiently, but it has limits when dealing with certain plant defenses like cellulose. Rather than viewing undigested corn as a failure of digestion, consider it proof of a functioning gut moving fibrous material along effectively.

By chewing thoroughly, choosing appropriate preparation methods, and maintaining a balanced diet rich in diverse fibers, you can enjoy corn without concern. Knowledge transforms confusion into confidence. Share this insight with others who might wonder what’s really happening when corn reappears—because understanding your body is the first step toward better health.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?