Modern life glorifies multitasking. We pride ourselves on answering emails during meetings, texting while driving, or studying with music and social media running in the background. But what if this so-called productivity is actually undermining our performance, focus, and mental well-being? The truth is, your brain isn’t built to handle multiple complex tasks simultaneously. Instead of boosting efficiency, multitasking often leads to more errors, longer completion times, and increased mental fatigue.

Understanding why multitasking fails requires diving into the neuroscience of attention, cognitive control, and brain structure. When we believe we’re multitasking, we’re usually rapidly switching between tasks—a process that consumes valuable neural resources and depletes mental energy far faster than sustained focus.

The Myth of Multitasking: What Science Says

Neuroscientists have long studied how the human brain manages attention. Functional MRI scans reveal that when engaged in a demanding cognitive task—such as problem-solving or reading—specific regions of the prefrontal cortex activate. This area governs executive function: planning, decision-making, and concentration. Crucially, these regions don’t split neatly to handle two unrelated tasks at once.

Instead, the brain toggles between tasks, a phenomenon known as “task-switching.” Each switch incurs a cognitive cost: milliseconds lost in reorienting attention, reconstructing context, and regaining momentum. These micro-delays accumulate, making multitasking slower and more error-prone than doing one thing at a time.

“People who think they are good at multitasking are actually the worst at it. They’re also the most likely to overestimate their abilities.” — Dr. David Strayer, Cognitive Neuroscientist, University of Utah

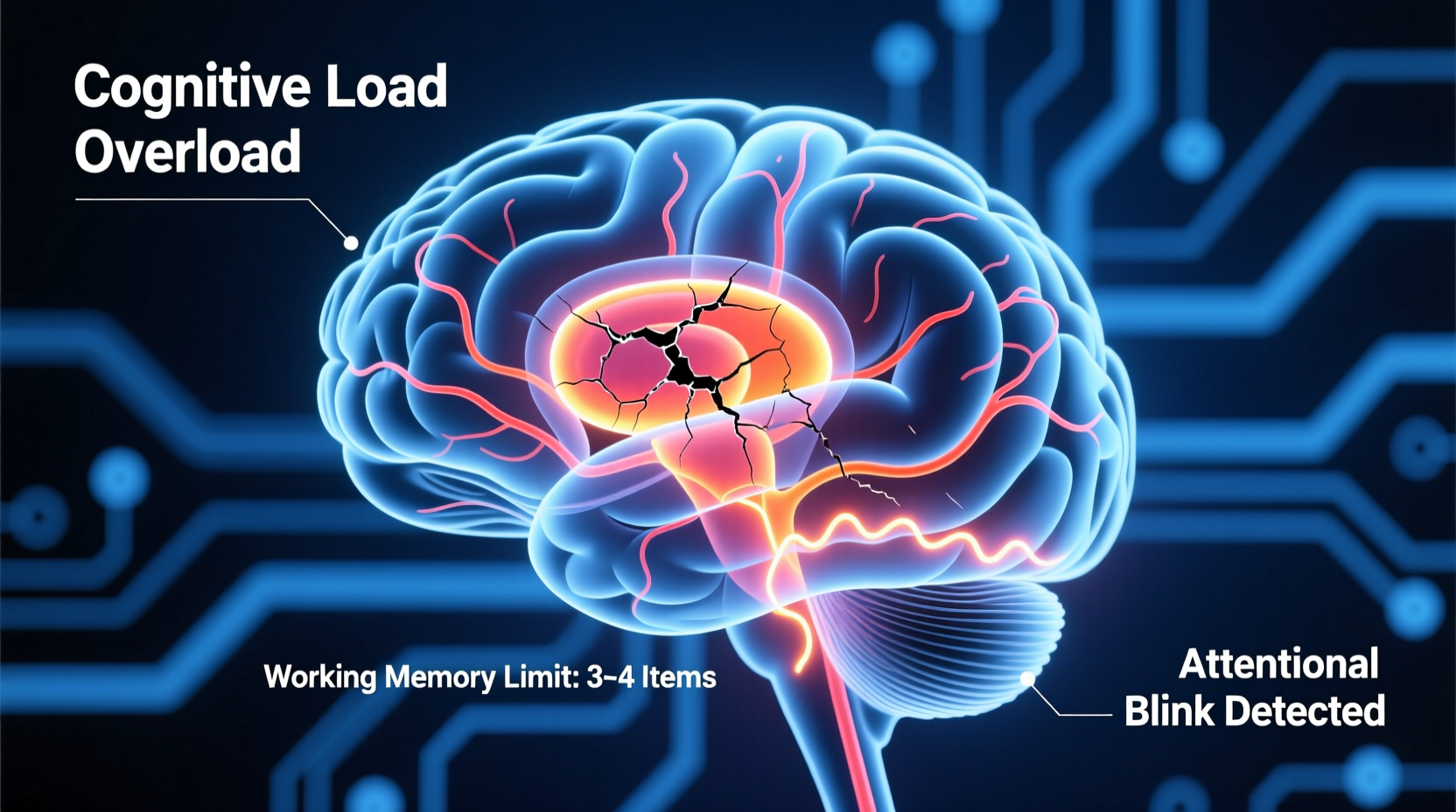

The Brain’s Bottleneck: Why Attention Is Limited

The human brain receives millions of sensory inputs every second. To prevent overload, it uses selective attention—a filtering mechanism that prioritizes relevant information. However, this system has a narrow bandwidth. Think of attention like a single-lane highway: only one vehicle (task) can pass through efficiently at a time.

When you attempt to juggle tasks, such as writing a report while listening to a podcast, both activities compete for the same cognitive pathways. Language processing, working memory, and comprehension all draw from overlapping neural networks. As a result, performance declines in one or both tasks—even if you don’t notice it immediately.

Task-Switching vs. True Multitasking

True multitasking—performing two cognitively demanding tasks simultaneously—is nearly impossible for humans. What we experience is task-switching, which gives the illusion of efficiency but comes at a high cost.

For example, imagine responding to a text message while writing an important email. You pause the email, shift attention to the message, reply, then return to the email. During that switch, you must:

- Disengage from the original task

- Activate rules and goals for the new task

- Execute the secondary task

- Re-engage with the primary task

Each transition takes time and mental effort. Research from the American Psychological Association shows that task-switching can reduce productivity by up to 40% and increase the likelihood of mistakes.

Real-World Consequences: A Mini Case Study

Sarah, a marketing manager, prided herself on her ability to manage five projects at once. She routinely attended Zoom calls while drafting campaign copy, checked Slack messages during strategy sessions, and reviewed spreadsheets while on phone calls. Over time, her team began noticing inconsistencies in her reports, missed deadlines, and frequent clarification requests.

After a project delay caused by a miscommunication she made during a distracted call, Sarah decided to reassess her workflow. She started scheduling focused blocks for each task, silencing notifications, and using a physical notebook to jot down interruptions for later. Within three weeks, her error rate dropped by 60%, and her team reported clearer communication. More importantly, Sarah felt less mentally drained at the end of the day.

Her experience reflects a broader truth: perceived busyness is not equivalent to effective output. Sustainable performance comes from depth, not distraction.

Cognitive Load and Mental Fatigue

Multitasking doesn’t just slow you down—it exhausts you. Every task switch increases cognitive load, the total amount of mental effort being used in working memory. High cognitive load impairs decision-making, reduces creativity, and accelerates burnout.

Chronic multitaskers often report higher stress levels and lower job satisfaction. A Stanford University study found that heavy media multitaskers performed worse on memory tests and were more easily distracted than those who focused on one medium at a time.

| Work Style | Focus Quality | Error Rate | Mental Energy Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multitasking | Fragmented | High | Very High |

| Single-Tasking | Deep | Low | Moderate |

| Structured Task Rotation | Controlled | Low-Moderate | Moderate-High |

How to Work With Your Brain, Not Against It

You can’t rewire your brain’s architecture, but you can adapt your habits to align with its natural strengths. Here’s a practical step-by-step guide to reducing reliance on multitasking:

- Identify high-focus tasks: List activities that require deep thinking, creativity, or precision (e.g., writing, coding, analyzing data).

- Schedule focus blocks: Allocate 25–90 minute uninterrupted periods for these tasks. Use calendar blocking to protect this time.

- Eliminate distractions: Turn off non-essential notifications, close unused browser tabs, and use tools like website blockers if needed.

- Batch low-cognition tasks: Group routine activities (like replying to emails or filing documents) into separate time slots.

- Use a “distraction notepad”: Keep a sheet of paper nearby to jot down intrusive thoughts or to-dos so you can return to them later without breaking flow.

Checklist: Building a Focus-Friendly Routine

- ✅ Audit your daily tasks: Which ones suffer when interrupted?

- ✅ Designate a distraction-free workspace

- ✅ Set specific times for checking email and messages

- ✅ Use headphones or a “do not disturb” sign during focus blocks

- ✅ Review your progress weekly and adjust schedules as needed

Frequently Asked Questions

Can some people really multitask effectively?

Very few can. While about 2–3% of the population are “supertaskers” who perform well under divided attention, most people—including those who believe they’re good at multitasking—experience significant performance drops. Don’t assume you’re the exception without testing it objectively.

Is listening to music while working considered multitasking?

It depends. Instrumental music with no lyrics may help some people by masking background noise and improving mood. However, lyrical music competes for language-processing centers in the brain and can impair reading comprehension and verbal reasoning. Test it yourself: compare your output quality with and without music.

What about walking and talking? Isn’t that multitasking?

Yes, but it works because walking is largely automatic for healthy adults. Once a skill becomes habitual and requires minimal conscious thought, it frees up cognitive resources. The issue arises when both tasks demand active attention—like navigating a busy street while on an important call.

Conclusion: Embrace Single-Tasking as a Superpower

In a world that rewards speed and constant activity, choosing to focus deeply on one thing at a time is a radical act. It’s also one of the most effective ways to improve the quality of your work, reduce stress, and reclaim control over your time. Your brain wasn’t designed to multitask—and now you know why.

Start small: pick one task today and give it your full attention from start to finish. Notice how much faster and more accurately you complete it. Over time, build a rhythm that honors your brain’s natural design. Productivity isn’t about doing more at once—it’s about doing what matters most, well.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?