Liquids surround us—water flows from our taps, fuel powers our vehicles, and blood circulates through our bodies. Yet despite their fluidity, one thing remains consistent: you can’t squeeze a liquid into a significantly smaller volume. Unlike gases, which compress easily under pressure, liquids resist compression with surprising strength. This fundamental property shapes everything from hydraulic systems to ocean depths. Understanding why liquids can’t be compressed reveals key insights into the nature of matter and energy.

The Nature of Molecular Packing in Liquids

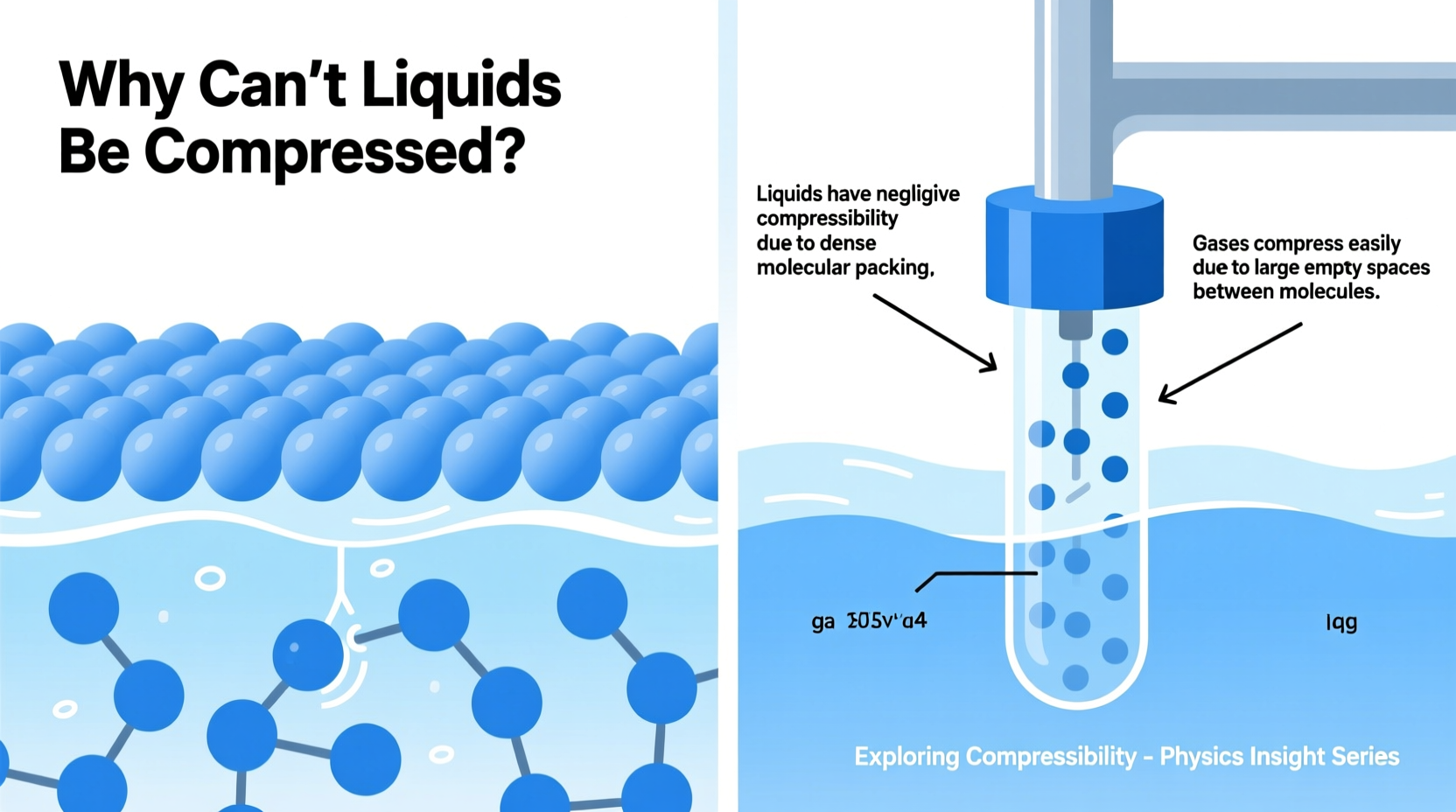

In any substance, compressibility depends on how closely its molecules are packed and how much empty space exists between them. In gases, molecules are far apart, moving freely and colliding infrequently. This large intermolecular space allows gases to be compressed dramatically when pressure is applied. Squeeze a gas, and those molecules simply move closer together.

Liquids, however, behave differently. Their molecules are already densely packed, held close by intermolecular forces such as hydrogen bonding or van der Waals interactions. While not rigidly fixed like solids, liquid molecules have minimal free space between them. When external pressure is applied, there’s little room for further reduction in volume because the molecules are essentially “touching” one another.

“Liquids occupy a middle ground between solids and gases—their density is high like solids, but their mobility resembles gases. This dense packing is what makes them nearly incompressible.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Physical Chemist, MIT

This near-incompressibility is not absolute, though. Under extreme pressures—such as those found deep in planetary interiors—some compression does occur. But for practical purposes on Earth, the change is negligible. For example, increasing water pressure by 1,000 atmospheres (about the pressure at 10 km below sea level) reduces its volume by only about 5%.

Comparative Compressibility: Liquids vs. Gases vs. Solids

To better understand liquid behavior, it helps to compare compressibility across states of matter. The table below summarizes key differences:

| State of Matter | Molecular Spacing | Compressibility | Example Response to Pressure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gas | Large gaps between molecules | Highly compressible | Volume reduced significantly under moderate pressure |

| Liquid | Tightly packed, minimal free space | Very low (practically incompressible) | Negligible volume change even under high pressure |

| Solid | Fixed, rigid lattice structure | Extremely low | May deform, but volume remains almost unchanged |

This comparison underscores why engineers rely on liquids in hydraulic systems—they transmit force efficiently because their volume doesn’t change under pressure.

Hydraulics: Leveraging Liquid Incompressibility

The principle that liquids cannot be compressed is the foundation of hydraulic technology. Hydraulic systems use enclosed fluids to transmit force from one point to another. Because the liquid doesn’t compress, applying pressure at one end instantly transfers that force to the other end.

Consider a simple hydraulic jack used to lift cars. A small force applied to a small piston creates pressure in the oil-filled chamber. Since the oil cannot compress, this pressure acts equally across the larger piston, generating a much greater output force—enough to lift heavy loads.

The formula governing this is Pascal’s Law: P = F/A, where pressure (P) is transmitted uniformly throughout the fluid. Without the incompressibility of the liquid, this force multiplication would fail. Any compression would absorb energy instead of transmitting it, making hydraulics inefficient or useless.

Real-World Example: Deep-Sea Submersibles

A compelling illustration of liquid behavior under pressure comes from deep-ocean exploration. At depths exceeding 8,000 meters, such as in the Mariana Trench, water pressure reaches over 800 atmospheres. Despite this immense force, seawater only compresses slightly—by less than 4%. Engineers designing submersibles must account for this minor compression, especially in buoyancy materials and sealed compartments.

In one case, the DSV Limiting Factor, a deep-diving submersible, uses syntactic foam for buoyancy. This material contains tiny glass spheres embedded in resin, designed to resist crushing under pressure. Interestingly, while the foam itself must withstand compression, the surrounding seawater remains largely incompressible—its density increases just enough to affect buoyancy calculations, but not enough to collapse structures.

Exceptions and Edge Cases

While we often say liquids are “incompressible,” this is a simplification useful for most applications. In reality, all materials compress to some degree. The measure of this is called the **bulk modulus**, which quantifies a substance’s resistance to uniform compression.

- Water has a bulk modulus of about 2.2 GPa—meaning it takes enormous pressure to reduce its volume.

- Mercury, being denser, has an even higher bulk modulus (~28 GPa), making it extremely resistant to compression.

- Liquid metals under high temperature and pressure, such as those in Earth’s outer core, exhibit measurable compression influencing geophysical models.

Even everyday scenarios reveal subtle effects. For instance, in high-pressure fuel injection systems in diesel engines, fuel oil experiences slight compression—around 1–2% under 2,000 bar pressure. Engineers must compensate for this “fluid elasticity” to ensure precise fuel delivery timing.

Step-by-Step: How Scientists Measure Liquid Compressibility

Determining how much a liquid compresses involves precise laboratory techniques. Here's a simplified overview of the process:

- Prepare a sealed chamber equipped with precision pressure sensors and volume displacement measurement tools.

- Fill the chamber with the test liquid, ensuring no air bubbles remain, as gases are highly compressible and would skew results.

- Apply controlled pressure increments using a hydraulic press or piston system, recording each pressure level.

- Measure minute changes in volume using laser interferometry or capacitive sensors capable of detecting micrometer-level shifts.

- Calculate the bulk modulus using the formula: K = -V (ΔP / ΔV), where K is the bulk modulus, V is initial volume, ΔP is pressure change, and ΔV is volume change.

- Analyze data to determine compressibility coefficient and compare with known values.

This method reveals that even \"incompressible\" liquids do yield slightly under pressure—just not enough to matter in most engineering contexts.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can any liquid be compressed significantly?

Under normal conditions, no liquid compresses significantly. However, under extreme pressures—such as those in planetary cores or experimental diamond anvil cells—liquids like hydrogen can undergo phase changes and exhibit measurable compression, sometimes transitioning into metallic states.

Why don’t liquids compress even when heated?

Heating a liquid usually causes expansion, not compression. Thermal energy increases molecular motion, pushing molecules slightly apart. While pressure can counteract this, heat alone does not compress liquids; it typically decreases density slightly.

If liquids are incompressible, why do scuba divers experience pressure changes?

Scuba divers feel pressure because water transmits force effectively due to its incompressibility. As depth increases, more water above exerts weight, increasing pressure linearly. It’s not that the water compresses onto them—it’s that the unyielding nature of the liquid ensures every meter of depth adds measurable pressure.

Checklist: Key Takeaways About Liquid Compressibility

- ✔ Liquids are densely packed at the molecular level, leaving little room for compression.

- ✔ Their near-incompressibility enables hydraulic systems to function efficiently.

- ✔ All liquids compress slightly under extreme pressure—measured via bulk modulus.

- ✔ Gases compress easily; solids and liquids do not, for different structural reasons.

- ✔ In engineering design, treating liquids as incompressible is a valid and useful assumption.

Conclusion: Embracing the Rigidity of Fluids

The inability of liquids to be compressed is not a limitation—it’s a powerful feature. From lifting heavy machinery to enabling life-supporting circulation in organisms, this property underpins both natural and engineered systems. Recognizing that fluidity and rigidity aren’t mutually exclusive allows us to harness liquids in smarter, more effective ways.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?