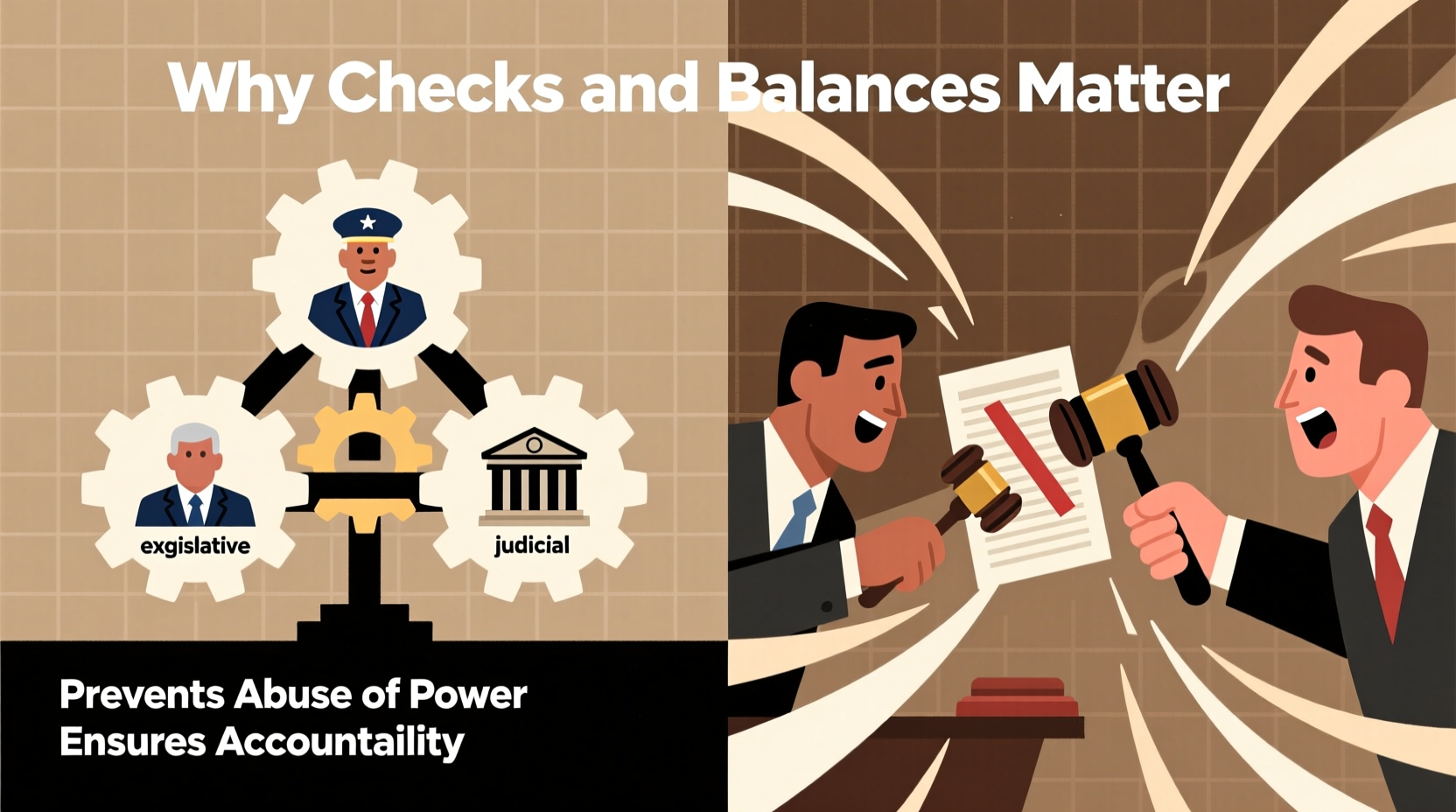

In any system of governance, power must be carefully distributed to prevent tyranny, corruption, and inefficiency. The principle of checks and balances is a foundational mechanism designed to ensure that no single branch of government becomes too powerful. Originating from Enlightenment-era political philosophy and enshrined in constitutions like that of the United States, this system enables mutual oversight among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. By distributing authority and enabling each branch to limit the actions of the others, checks and balances uphold the rule of law and protect democratic values.

The Origins and Purpose of Checks and Balances

The concept of dividing governmental power can be traced back to ancient Greece and Rome, but it was most influentially articulated by French philosopher Montesquieu in his 1748 work The Spirit of the Laws. He argued that liberty could only be preserved if power was separated into distinct branches—legislative, executive, and judicial—and if each had the ability to check the others.

This idea directly influenced the framers of the U.S. Constitution, who sought to avoid the concentration of power they had experienced under British monarchy. James Madison emphasized in Federalist No. 51 that “ambition must be made to counteract ambition,” meaning that self-interest within government institutions could be harnessed to maintain equilibrium.

“Power divided among branches ensures that freedom endures. No one person or group should hold unchecked control.” — James Madison, Father of the U.S. Constitution

The primary purposes of checks and balances include:

- Preventing the accumulation of power in one branch

- Ensuring accountability and transparency

- Protecting individual rights and civil liberties

- Maintaining the stability and legitimacy of government

How Checks and Balances Work in Practice

In functional democracies, checks and balances manifest through specific constitutional powers granted to each branch. These mechanisms allow for oversight, correction, and collaboration while preventing overreach.

Consider the U.S. federal government as a model:

| Branch | Checks on Executive | Checks on Legislative | Checks on Judicial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legislative | Can override presidential vetoes with 2/3 vote; confirms appointments; controls budget; can impeach president | - | Confirms judicial appointments; can impeach judges; proposes constitutional amendments |

| Executive | - | Can veto legislation; proposes laws and budgets; issues executive orders (within limits) | Appoints federal judges; can pardon individuals convicted by courts |

| Judicial | Can declare executive actions unconstitutional | Can strike down laws as unconstitutional | - |

This interdependence forces cooperation and negotiation. For example, while Congress passes laws, the president can veto them. However, Congress may still enact the law by overriding the veto with sufficient support. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court can invalidate laws or executive actions it deems unconstitutional—a power established in Marbury v. Madison (1803).

Real-World Example: Watergate and the Limits of Power

The Watergate scandal of the 1970s offers a powerful illustration of checks and balances in action. President Richard Nixon attempted to conceal his administration’s involvement in a break-in at Democratic National Committee headquarters. Initially, the executive branch used its influence to obstruct investigations.

However, the system responded:

- Congress launched hearings and subpoenaed evidence, including the infamous White House tapes.

- The judiciary, particularly the Supreme Court in United States v. Nixon (1974), ruled unanimously that the president could not withhold evidence under claims of executive privilege.

- Special prosecutors and investigative journalists applied external pressure, demonstrating how civic institutions complement formal checks.

Faced with near-certain impeachment by the House and conviction in the Senate, Nixon resigned—the first and only U.S. president to do so. This episode proved that even the most powerful office is subject to legal and institutional constraints when checks function effectively.

Common Threats to Effective Checks and Balances

While the framework is robust, it is not immune to erosion. Several modern challenges threaten its integrity:

- Partisan loyalty overriding institutional duty: Legislators may prioritize party allegiance over holding the executive accountable.

- Expansion of executive orders: Bypassing Congress through unilateral actions undermines legislative authority.

- Politicization of the judiciary: When judicial appointments become highly ideological, public trust in impartiality declines.

- Public apathy: Without informed civic engagement, abuses may go unnoticed or unchallenged.

These risks highlight that constitutional design alone is insufficient. A culture of accountability, a free press, and an educated citizenry are equally vital.

Actionable Checklist: Supporting Checks and Balances

Every citizen plays a role in preserving this system. Use this checklist to contribute:

- Stay informed about government actions and proposed legislation.

- Vote in all elections, including judicial and local races.

- Hold elected officials accountable through letters, calls, or public forums.

- Support independent media and fact-based reporting.

- Advocate for transparent processes and ethical leadership.

- Resist normalizing authoritarian rhetoric or actions.

FAQ: Common Questions About Checks and Balances

Why don’t checks and balances lead to gridlock?

While debate and delay are possible outcomes, they are often features, not flaws. Slower decision-making allows for greater scrutiny, compromise, and prevention of rash policies. Gridlock becomes problematic only when cooperation breaks down entirely due to extreme partisanship.

Can checks and balances exist in non-democratic systems?

Rarely, and not effectively. Authoritarian regimes may have nominal branches of government, but without independent judiciaries, free elections, or legislative autonomy, true checks do not exist. Any limitations on power are typically internal and unaccountable.

What happens when one branch oversteps its authority?

Other branches respond using their constitutional tools. For instance, if a court strikes down a law, the legislature may revise it to comply with constitutional standards. If the president exceeds executive authority, courts can issue injunctions or Congress can initiate investigations or impeachment.

Conclusion: Safeguarding Democracy Through Balance

Checks and balances are more than a structural feature of government—they are a living safeguard against the corruption of power. Their strength lies not in perfection, but in persistence: the continuous push and pull between branches that keeps democracy resilient. History shows that when these mechanisms weaken, freedoms erode. Conversely, when citizens remain vigilant and institutions act with integrity, the system can correct itself even in times of crisis.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?