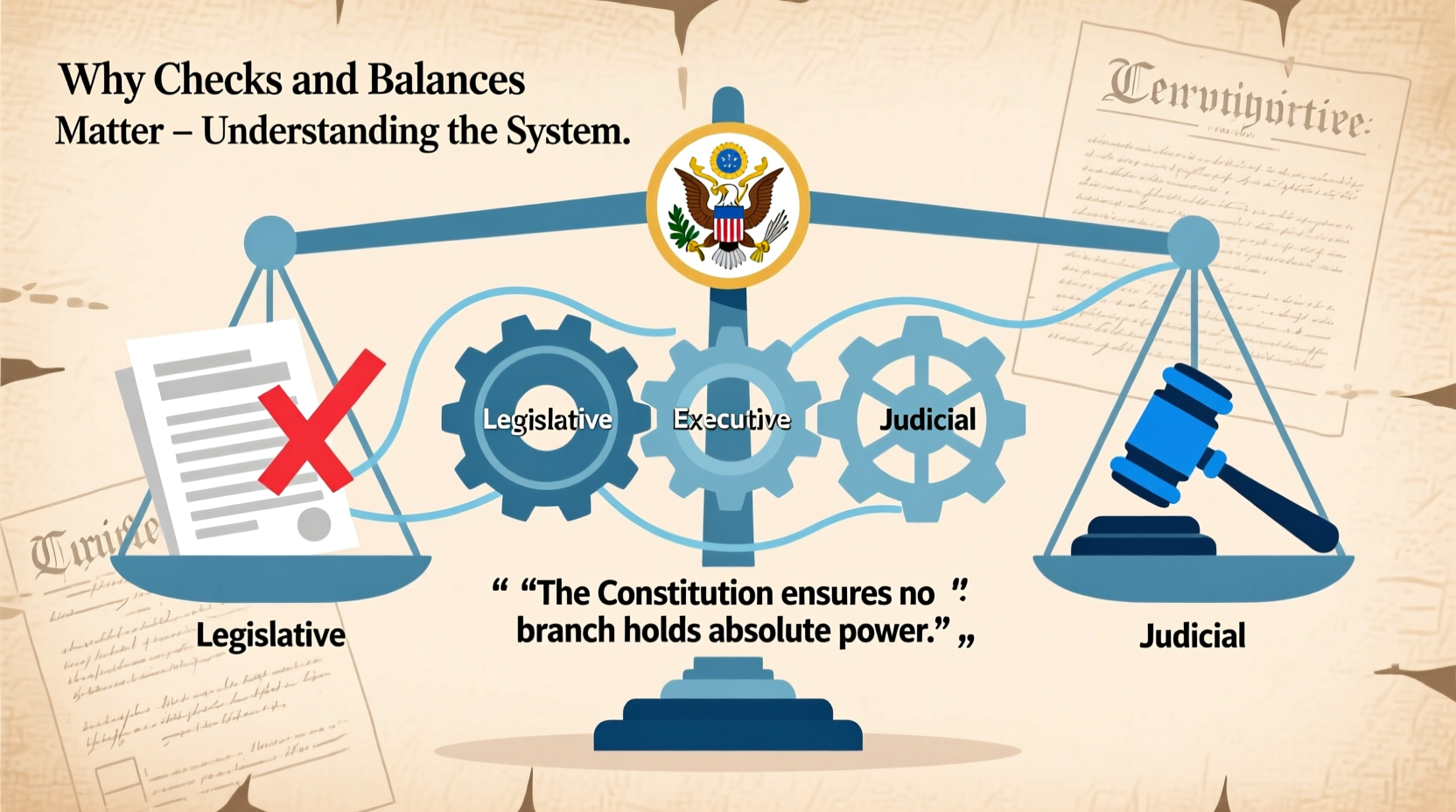

In any democratic government, the concentration of power poses a significant risk to freedom, fairness, and justice. To prevent tyranny and ensure that no single branch dominates, modern democracies rely on a system known as checks and balances. This mechanism divides governmental authority among separate branches—typically legislative, executive, and judicial—each with distinct powers and responsibilities. More importantly, each branch has the ability to limit or check the actions of the others. The result is a dynamic equilibrium designed to promote accountability, protect civil liberties, and preserve the rule of law.

The Origins and Purpose of Checks and Balances

The concept of separating governmental powers dates back to ancient philosophers like Aristotle and Polybius, but it was most influentially developed during the Enlightenment. French political thinker Montesquieu articulated the idea in his 1748 work *The Spirit of the Laws*, arguing that liberty could only be preserved if power was divided. His ideas profoundly influenced the framers of the U.S. Constitution, who embedded checks and balances into the nation’s foundational document.

The primary purpose of this system is not merely to divide power, but to create interdependence. No branch can function effectively without some level of cooperation from the others. For example, while Congress passes laws, the president can veto them. Yet Congress can override that veto with a two-thirds majority. Similarly, the judiciary can strike down unconstitutional laws, but judges are appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. These overlapping authorities ensure that decisions are scrutinized from multiple angles before becoming policy.

“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” — Lord Acton, Historian

This famous warning underscores why systems of restraint are essential. Without checks and balances, even well-intentioned leaders may gradually accumulate excessive control, leading to erosion of rights and institutional decay.

How the Three Branches Check Each Other

To fully appreciate the importance of checks and balances, it's critical to understand how each branch interacts with the others. Below is a breakdown of key mechanisms:

| Branch | Checks on Executive | Checks on Legislative | Checks on Judicial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legislative (Congress) | Can override presidential vetoes; controls budget; confirms appointments; can impeach and remove the president | Creates laws; initiates impeachment of judges; sets court jurisdiction | Confirms judicial appointments; can initiate constitutional amendments to overturn rulings |

| Executive (President) | N/A | Can veto legislation; proposes budgets and policies; issues executive orders (within limits) | Appoints federal judges and Supreme Court justices; can pardon individuals convicted of federal crimes |

| Judicial (Courts) | Can declare executive actions unconstitutional; reviews legality of regulations and orders | Can invalidate laws that violate the Constitution; interprets statutory language | Life tenure protects independence; decisions based on constitutional interpretation |

This intricate web of oversight ensures that unilateral action is difficult and that major decisions undergo rigorous review. It slows down governance at times, but that friction is intentional—it forces deliberation and reduces rash or authoritarian decision-making.

Real-World Example: The Watergate Scandal

A powerful illustration of checks and balances in action occurred during the Watergate scandal of the early 1970s. When journalists uncovered evidence of a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters linked to President Richard Nixon’s re-election team, investigations revealed a widespread cover-up orchestrated from within the White House.

Despite Nixon’s attempts to obstruct justice and assert executive privilege, other branches stepped in. The judiciary ruled that the president must release incriminating tapes. Congress launched bipartisan hearings and moved toward impeachment. Ultimately, facing near-certain removal from office, Nixon resigned in 1974—the first and only U.S. president to do so.

This case demonstrates how the system works under pressure. Even when one branch tries to evade accountability, the others have tools to enforce transparency and uphold the law. As Senator Barry Goldwater reportedly told Nixon: “I think you should resign. I’ve had it checked. There are enough votes in the Senate to convict you.” That moment was not just political—it was constitutional resilience in motion.

Threats to the System and How to Protect It

While checks and balances are robust in theory, they depend on institutional integrity and public vigilance. Several modern challenges threaten their effectiveness:

- Partisan loyalty overriding duty: Legislators may avoid checking a president from their own party, weakening oversight.

- Executive overreach: Expansion of emergency powers or use of unilateral executive orders can bypass legislative input.

- Polarization of the judiciary: When judicial appointments become highly politicized, public trust in impartial courts erodes.

- Public apathy: When citizens disengage, there is less pressure on officials to act responsibly.

To strengthen the system, reforms and civic engagement are essential. Independent ethics rules for all branches, transparent appointment processes, and stronger enforcement of accountability mechanisms can help restore balance.

Actionable Checklist for Citizens

- Stay informed about proposed legislation and executive actions.

- Contact elected representatives when concerned about overreach.

- Support nonpartisan watchdog organizations that monitor government conduct.

- Vote in all elections—not just presidential, but also congressional and judicial races.

- Advocate for term limits or ethics reforms where appropriate.

Frequently Asked Questions

What happens if one branch ignores the others?

If a branch consistently disregards constitutional limits—such as a president refusing to comply with court orders or Congress ignoring judicial rulings—it risks triggering a constitutional crisis. Historical precedents show that such moments often lead to legal battles, public protests, or even impeachment proceedings. The system is designed to respond, but it requires active participation from both institutions and citizens.

Are checks and balances unique to the United States?

No. While the U.S. model is one of the most well-known, many democracies incorporate similar principles. The United Kingdom, though parliamentary, has an independent judiciary and media scrutiny that serve as informal checks. Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court can invalidate laws, and Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms enables judicial review. Variations exist, but the core idea—preventing concentration of power—is universal in functioning democracies.

Can checks and balances slow down government too much?

Yes, at times. Gridlock can occur when branches are controlled by opposing parties or when compromise fails. However, this \"slowness\" is often a feature, not a bug. It prevents hasty legislation, protects minority interests, and ensures broader consensus. The goal is not efficiency above all, but thoughtful, sustainable governance.

Conclusion: Safeguarding Democracy Requires Vigilance

Checks and balances are not self-executing. They rely on individuals—judges, lawmakers, presidents, and citizens—who value the rule of law over short-term gains. History shows that democracies unravel not through sudden coups, but through gradual erosion of norms and institutions. Understanding this system is the first step toward protecting it.

In an era of rising polarization and misinformation, civic literacy is more vital than ever. By learning how power is distributed and monitored, people gain the tools to question authority, demand transparency, and participate meaningfully in governance. The strength of a democracy lies not in its perfection, but in its capacity for correction—and checks and balances make that possible.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?