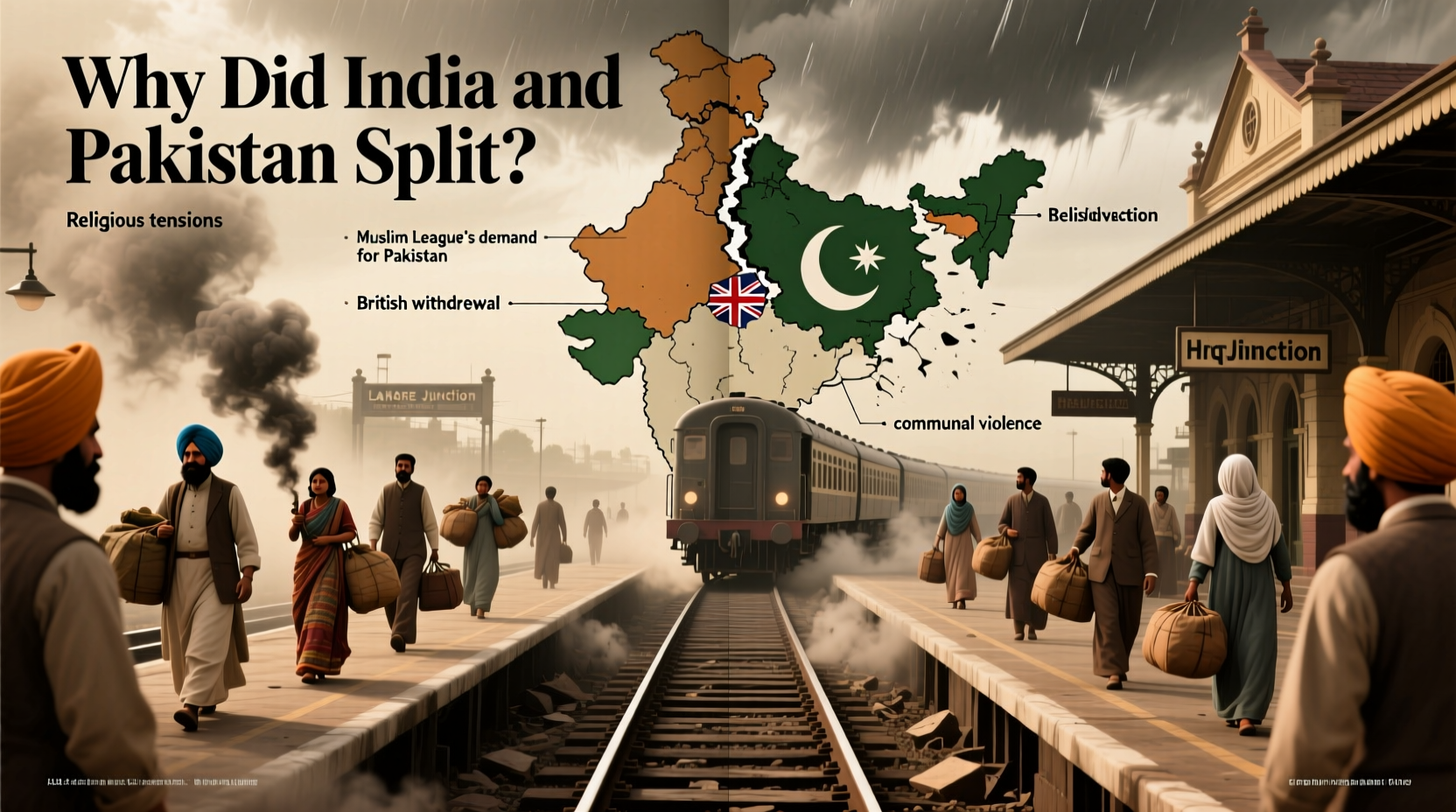

The partition of British India in 1947 remains one of the most defining and traumatic events in modern South Asian history. It led to the creation of two independent nations—India and Pakistan—along religious lines, triggering mass migrations, widespread violence, and enduring geopolitical tensions. Understanding why India and Pakistan split requires examining a complex mix of colonial policies, religious identity politics, political maneuvering, and social fragmentation that unfolded over decades.

Colonial Roots: The British Divide-and-Rule Strategy

British colonial rule in India, which lasted from 1858 until 1947, played a foundational role in deepening religious divisions between Hindus and Muslims. While religious coexistence had long existed across the subcontinent, British administrators increasingly categorized people by religion for governance and census purposes. This institutionalized religious identity as a primary political marker.

Policies such as separate electorates introduced under the Morley-Minto Reforms (1909) and expanded in the Government of India Act (1935) allowed Muslims to vote for Muslim candidates only. Though intended to protect minority interests, these measures reinforced communal identities and laid the groundwork for political separatism.

“Divide et impera [divide and rule] was practiced so successfully in India that it ultimately resulted in division.” — Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, Indian scholar and architect of the Constitution

Rise of Communal Politics and the Two-Nation Theory

A central ideological force behind the split was the “Two-Nation Theory,” championed by the All-India Muslim League under Muhammad Ali Jinnah. The theory asserted that Hindus and Muslims were not merely religious groups but distinct nations with incompatible cultures, traditions, and legal systems. Therefore, they could not coexist in a single nation without Muslim rights being overshadowed by the Hindu majority.

Initially, many Muslim leaders, including Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, advocated for education and integration rather than separation. However, growing fears of marginalization in a post-colonial India dominated by the Indian National Congress—a party perceived as Hindu-centric—shifted sentiment toward separatism.

The Muslim League’s demand for Pakistan gained momentum after the 1946 provincial elections, where it won nearly all Muslim-reserved seats. The failure of the Cabinet Mission Plan (1946), which proposed a united India with significant autonomy for Muslim-majority regions, further pushed leaders toward partition.

Key Events Leading to Partition

The path to partition was marked by escalating tension and violence. Several pivotal moments made division seem inevitable:

- 1940 Lahore Resolution: The Muslim League formally demanded independent states for Muslims in northwestern and eastern India.

- 1946 Direct Action Day: Called by Jinnah to press for Pakistan, it triggered massive riots in Calcutta, leaving thousands dead and marking a turning point toward irreversible communal hostility.

- Mountbatten's Appointment (1947): Lord Louis Mountbatten, the last Viceroy, accelerated independence plans due to rising unrest, opting for a swift partition despite inadequate preparation.

- Radcliffe Line (August 1947): Drawn by British lawyer Cyril Radcliffe in just five weeks, the border divided Punjab and Bengal with little regard for local communities, leading to chaotic population transfers.

Timeline of Critical Milestones

| Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1906 | Formation of All-India Muslim League | Political platform for Muslim interests |

| 1940 | Lahore Resolution | First formal call for a separate Muslim state |

| 1946 | Direct Action Day & Cabinet Mission Failure | Communal violence escalates; unity talks collapse |

| 1947 | Mountbatten announces June 3 Plan | Official acceptance of partition |

| Aug 14–15, 1947 | Pakistan and India gain independence | Partition implemented overnight |

Human Cost and Immediate Aftermath

The actual partition was executed with astonishing speed and minimal planning. The result was one of the largest forced migrations in human history—between 10 to 15 million people crossed newly drawn borders. Hindus and Sikhs moved from Pakistan to India; Muslims migrated in the opposite direction.

Tragically, up to one million people are estimated to have died in sectarian violence during the migration. Trains arrived filled with corpses; entire villages were wiped out. Women were abducted, assaulted, or killed in targeted attacks aimed at erasing cultural identity.

The division of Punjab and Bengal—both ethnically and linguistically mixed regions—was especially devastating. Families were torn apart, properties abandoned, and livelihoods destroyed overnight. The trauma of partition continues to echo through generations in both countries.

“My father never spoke of Lahore again. He said his heart broke when he left his home, knowing he’d never see it.” — A survivor’s account recorded by Urvashi Butalia, historian and author of *The Other Side of Silence*

Legacy and Ongoing Tensions

The split between India and Pakistan did not end with 1947. It established a legacy of mutual distrust, territorial disputes, and recurring conflict. Key issues include:

- Kashmir Conflict: The princely state’s ambiguous accession sparked the first Indo-Pak war in 1947–48 and remains a flashpoint today.

- Diplomatic Hostility: Wars erupted in 1965, 1971 (which led to the creation of Bangladesh), and 1999 (Kargil).

- Nuclear Rivalry: Both nations became nuclear powers by 1998, raising global concerns about regional stability.

- Cultural Memory: National narratives in both countries often emphasize victimhood and blame, hindering reconciliation.

Mini Case Study: The Punjab Border Today

Consider the town of Attari in India and Wagah in Pakistan. Once part of a unified Punjabi culture, they now host a daily military ceremony—the Wagah-Attari border closing—that draws tourists with its theatrical display of rivalry. Yet, behind the spectacle, families on both sides still mourn lost connections. Elders recall sharing festivals, languages, and food before 1947. Today, visas are hard to obtain, and reunions remain rare. This symbolic border encapsulates how political division has entrenched emotional and cultural separation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Was the partition inevitable?

No historical event is truly inevitable. While religious tensions and political demands grew, alternative paths like a federated, decentralized India were discussed. Poor leadership decisions, rushed timelines, and lack of public consultation made partition the chosen—but not predestined—solution.

Did Gandhi support the partition?

No. Mahatma Gandhi was a staunch opponent of partition. He believed in Hindu-Muslim unity and fasted in 1947 to stop violence in Calcutta. His opposition cost him political influence among Congress leaders who saw partition as the only way to achieve a timely transfer of power.

Why was Bangladesh created later if Pakistan was already a Muslim state?

East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) was separated from West Pakistan by over 1,000 miles of Indian territory. Despite shared religion, linguistic, cultural, and economic disparities led to neglect and oppression. After a brutal war in 1971, supported by India, East Pakistan gained independence as Bangladesh.

Conclusion: Learning from History

The split between India and Pakistan was not the result of ancient hatreds, but of specific historical forces—colonial manipulation, elite-driven politics, and the failure to build inclusive national identities. Its consequences continue to shape South Asia’s politics, security, and societies.

Recognizing the human cost of partition is essential for fostering empathy and preventing future divisions along religious or ethnic lines. By preserving personal stories, teaching nuanced history, and promoting dialogue, both nations can move beyond inherited animosities.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?