The Korean Peninsula has been divided for over seven decades, with North Korea and South Korea existing as two separate nations under vastly different ideologies. This division is not merely a geographic line but a deep political, economic, and cultural chasm shaped by war, ideology, and global power struggles. Understanding why Korea split requires examining a complex history that spans colonial rule, World War II, Cold War tensions, and a devastating conflict that never officially ended.

The End of Japanese Occupation and the Power Vacuum

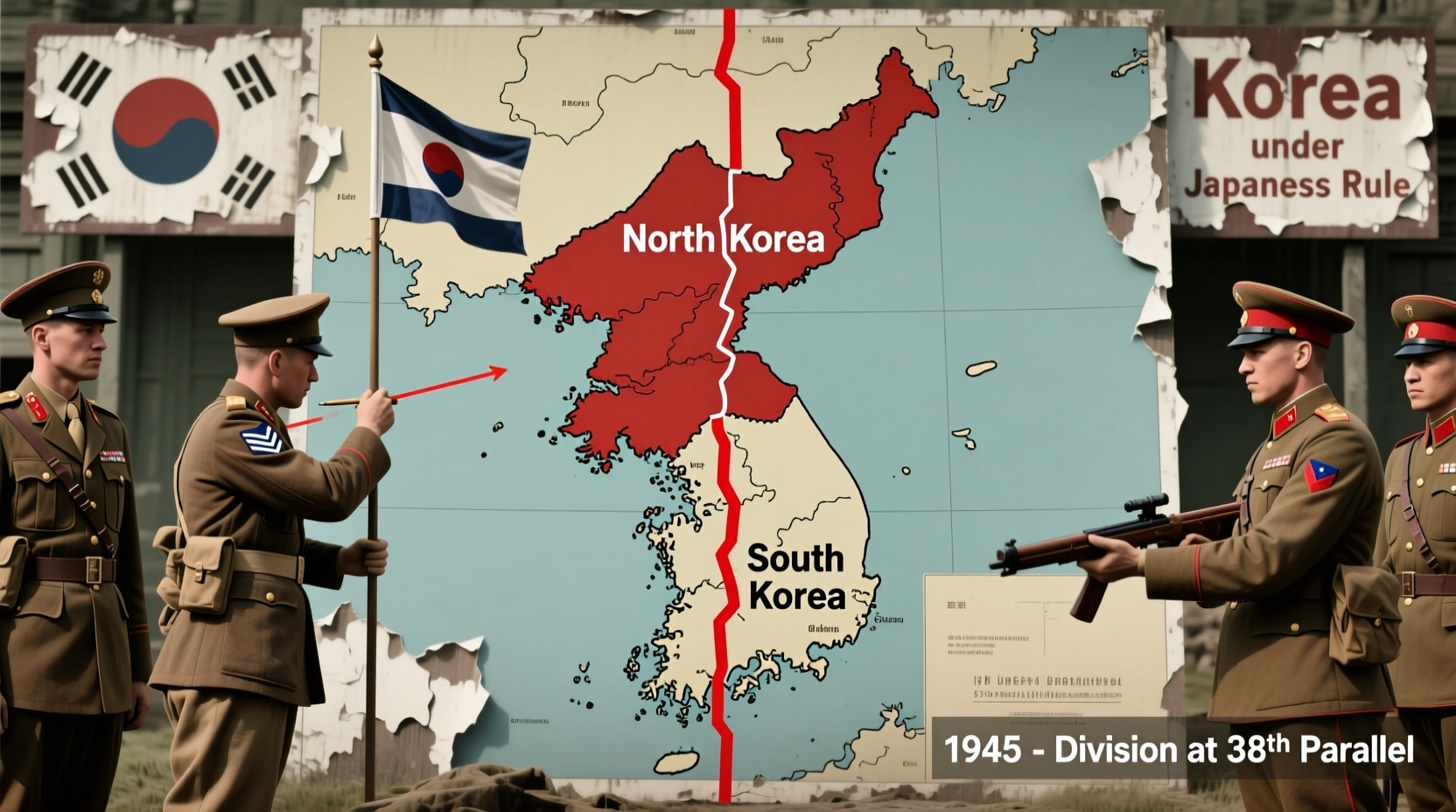

Korea was under Japanese colonial rule from 1910 to 1945. During this period, Japan suppressed Korean culture, language, and political autonomy. When Japan surrendered at the end of World War II in August 1945, Korea was suddenly liberated—but without a clear path to independence or self-governance. The absence of a unified Korean government created a power vacuum, prompting external powers to step in.

The United States and the Soviet Union, wartime allies who were already developing ideological differences, agreed to temporarily divide Korea along the 38th parallel. The Soviets would accept the Japanese surrender north of the line; the Americans would do so to the south. This arrangement, intended as a short-term military measure, quickly solidified into a lasting political divide.

Cold War Ideologies Take Root

As the Cold War intensified between the U.S. and the USSR, Korea became a proxy battleground for competing systems: capitalism and democracy versus communism and authoritarianism. In the South, the U.S. supported Syngman Rhee, a staunch anti-communist, helping establish the Republic of Korea (ROK) in 1948. In the North, the Soviets backed Kim Il-sung, a communist revolutionary, leading to the creation of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK).

Neither side recognized the other’s legitimacy. Both claimed sovereignty over the entire peninsula, setting the stage for inevitable conflict. Elections held in 1948 were only recognized in the South and by Western nations; the North dismissed them as illegitimate.

“Korea was not divided by its people, but by foreign powers with their own strategic interests.” — Bruce Cumings, Professor of History, University of Chicago

The Korean War and the Cementing of Division

In June 1950, North Korea launched a surprise invasion of South Korea, crossing the 38th parallel with Soviet-backed tanks and troops. The attack marked the beginning of the Korean War, a brutal three-year conflict that drew in China, the United States, and United Nations forces supporting the South.

The war saw dramatic shifts in control—Seoul changed hands four times—and resulted in an estimated 2–3 million civilian and military deaths. By 1953, the front lines had stabilized near where they began. An armistice was signed on July 27, 1953, halting hostilities but not ending the war. To this day, no peace treaty has been signed, meaning North and South Korea are technically still at war.

The Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), a 250-kilometer-long buffer zone established by the armistice, remains one of the most heavily fortified borders in the world.

Key Events Leading to Division

| Year | Event | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | Japan annexes Korea | Begins 35 years of colonial rule |

| 1945 | Japan surrenders; U.S. and USSR divide Korea at 38th parallel | Temporary split becomes entrenched |

| 1948 | Republic of Korea (South) and DPRK (North) formally established | Dual governments claim legitimacy |

| 1950 | North invades South, starting Korean War | Internationalization of conflict |

| 1953 | Armistice signed; DMZ established | War suspended, not ended |

Long-Term Consequences of the Split

The division has led to starkly different trajectories for the two Koreas. South Korea evolved into a vibrant democracy and economic powerhouse, known for its technological innovation and cultural exports. North Korea, under the Kim dynasty, developed into one of the world’s most isolated and repressive regimes, prioritizing military strength and state control over economic development and human rights.

Milions of families remain separated, with little to no communication across the border. Attempts at reconciliation—such as the 2000 inter-Korean summit and periodic reunions of separated families—have offered brief hope but no lasting resolution.

Mini Case Study: The Park Family Reunion

In 2015, the Park family participated in a rare government-organized reunion event at Mount Kumgang. Brothers separated since 1950 met for just three days. One brother, living in Seoul, described holding his sibling’s hand and weeping, knowing they might never see each other again. These emotional gatherings highlight the deeply personal toll of political division.

What Could Reunification Look Like?

While reunification remains a distant possibility, experts have explored several models:

- German Model: Full integration after the fall of East Germany—costly but successful.

- Federal System: A single nation with two semi-autonomous regions maintaining distinct economies and governance.

- Confederation: Two sovereign states cooperating on defense, economy, and diplomacy while retaining independence.

Challenges include vast economic disparities (South Korea’s GDP is over 50 times larger than North Korea’s), infrastructure gaps, and political distrust. Any reunification would require immense international support and long-term planning.

Checklist: Key Factors Behind Korea’s Division

- End of Japanese colonial rule creating a leadership vacuum

- U.S.-Soviet agreement to divide Korea at the 38th parallel

- Rise of Cold War tensions and ideological polarization

- Establishment of rival governments in 1948

- North Korea’s 1950 invasion and the outbreak of the Korean War

- 1953 armistice that froze, but did not resolve, the conflict

- Ongoing lack of diplomatic recognition and peace treaty

FAQ

Is North Korea the same country as South Korea?

No. Although both claim to represent the entire Korean Peninsula, they are separate sovereign states with different governments, economies, and political systems. They have been divided since 1945.

Why hasn’t the Korean War officially ended?

The war ended in an armistice, not a peace treaty. Ongoing tensions, lack of trust, and geopolitical complexities—especially involving the U.S., China, and regional security—have prevented formal peace negotiations from succeeding.

Can South Koreans visit North Korea?

Generally, no. Travel to North Korea by South Koreans requires special permission from both governments and is extremely rare. Most visits occur only during diplomatic or humanitarian programs.

Conclusion

The division of Korea was not the result of internal conflict alone but a consequence of imperial collapse, great-power politics, and the ideological rift of the Cold War. What began as a temporary military decision turned into one of the world’s longest-standing geopolitical standoffs. While the world moves forward, millions on the Korean Peninsula live with the legacy of a war that never truly ended.

Understanding this history is essential—not only for grasping current events on the peninsula but for recognizing how global decisions can reshape nations for generations. As dialogue continues, even in small steps, the hope for peace and eventual reconciliation persists.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?