Sourdough baking is as much science as it is art. When your loaf collapses, spreads out like a pancake, or fails to rise properly, it’s easy to feel defeated. But flat sourdough is rarely due to one single mistake—it’s usually a combination of factors affecting fermentation, gluten development, shaping, or oven spring. Understanding the root causes allows you to adjust your process and achieve that dreamy, open-crumbed, well-risen loaf.

Flat loaves are among the most common sourdough frustrations. Whether you're a beginner or have been baking for years, diagnosing the issue requires attention to detail at every stage: starter health, mixing, bulk fermentation, shaping, proofing, and baking. This guide breaks down each potential culprit and offers actionable solutions so you can consistently produce beautiful, tall sourdough bread.

Starter Strength: The Foundation of Rise

Your sourdough starter is the engine behind your loaf’s rise. If it's weak, inactive, or underfed, your dough won’t generate enough gas to lift itself during proofing and baking. A healthy starter should double predictably within 4–8 hours of feeding, with visible bubbles throughout and a pleasant tangy aroma.

If your starter peaks too early (within 3–4 hours) and then collapses, it may be overactive but not sustained—common in warm environments. Conversely, if it barely rises after 12 hours, it lacks strength. Either scenario leads to poor oven spring and flat bread.

To test starter readiness, perform the float test: drop a small spoonful into room-temperature water. If it floats, it's producing enough CO₂ to leaven dough. However, this test isn't foolproof—some strong starters sink due to density. Better indicators include consistent doubling time and bubbly texture.

“Your starter isn’t just alive—it needs to be robust and predictable. Consistency beats convenience.” — Daniel Leader, author of *Local Breads*

Gluten Development and Dough Structure

A strong gluten network is essential for trapping the gases produced by fermentation. Without sufficient structure, your dough expands outward instead of upward, resulting in a flat, dense loaf.

Underdeveloped gluten often stems from insufficient mixing or kneading, especially when working with high-hydration doughs. On the other hand, overmixing can damage the gluten matrix, particularly when using stand mixers on high speed. The ideal approach depends on your method—autolyse, stretch and folds, or mechanical mixing—but all aim to create a smooth, elastic, and slightly tacky dough.

Perform the windowpane test: pinch off a small piece of dough and gently stretch it between your fingers. If it forms a thin, translucent membrane without tearing, gluten development is adequate. If it tears easily, more development is needed.

Stretch and Fold Guide for Optimal Gluten

- Mix flour, water, and starter; let rest 30 minutes (autolyse).

- Add salt and mix thoroughly.

- Perform 4 sets of stretch and folds, spaced 15–30 minutes apart during the first half of bulk fermentation.

- Each set: grab one side of the dough, stretch it upward, and fold it over the center. Rotate bowl and repeat 3–4 times.

- Allow dough to rest between sets to relax the gluten.

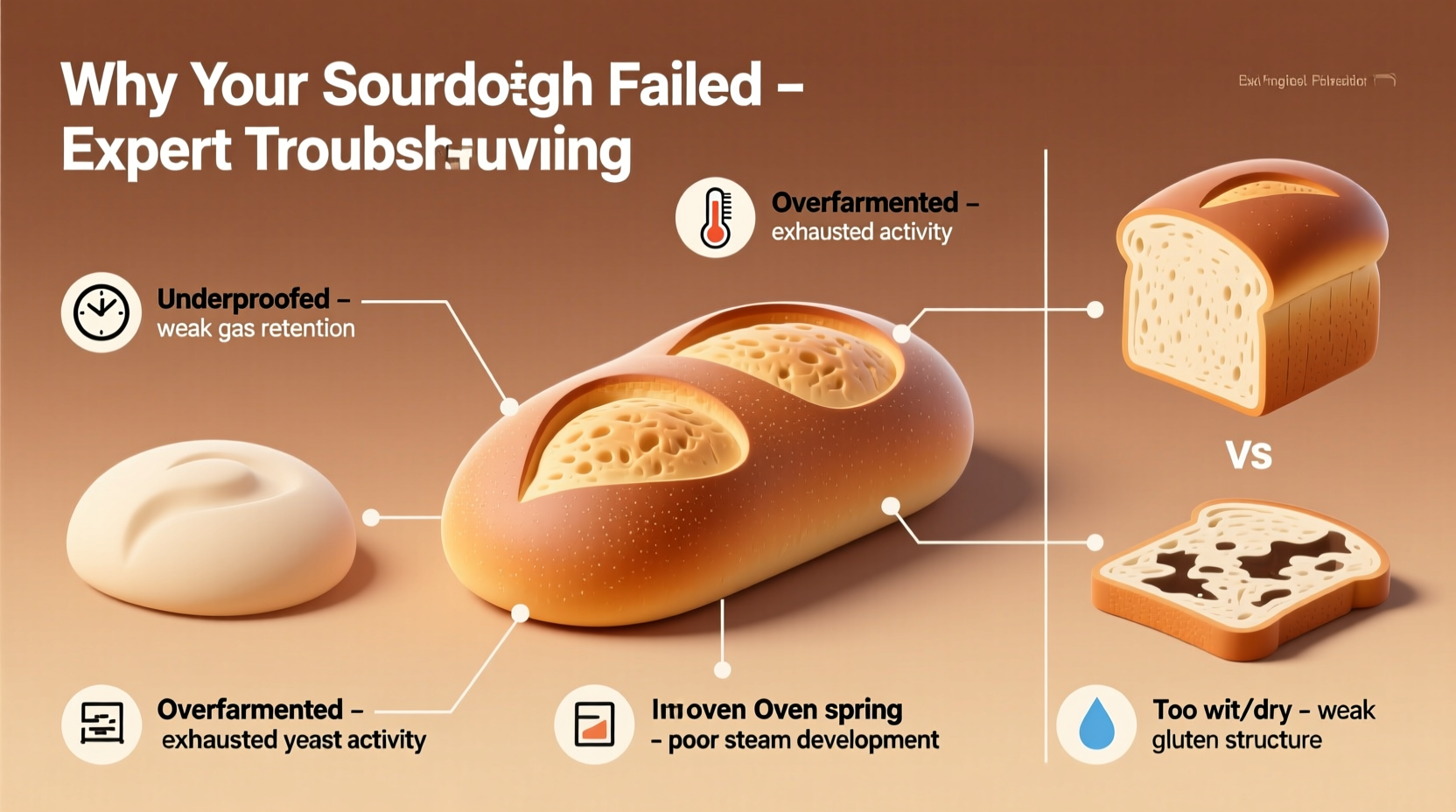

Proofing Problems: Under vs. Over

One of the leading causes of flat sourdough is incorrect proofing. Both underproofed and overproofed dough collapse in the oven, but for different reasons.

Underproofed dough hasn’t fermented long enough to develop gas pockets and extensibility. It may appear tight and resist scoring, and while it might hold shape pre-bake, it lacks the internal energy to expand in the oven. Result: a dense crumb and minimal rise.

Overproofed dough has fermented too long. The gluten structure weakens, and gas bubbles grow too large and unstable. When transferred to the baking vessel or scored, the dough deflates. In extreme cases, it spreads immediately upon loading into the oven.

To assess proof readiness, use the poke test: lightly press a fingertip about ½ inch into the dough. If it springs back slowly and leaves a slight indentation, it’s ready. If it springs back instantly, it needs more time. If it doesn’t spring back at all and feels gassy or fragile, it’s overproofed.

| Proofing Issue | Signs | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Underproofed | Tight surface, no indentation after poke, dense crumb | Extend bulk fermentation or final proof by 30–60 min |

| Overproofed | Deflates when touched, sticky, spreads quickly | Bake immediately or reshape and reproof briefly (if structure remains) |

| Temperature Too Cold | Slow rise, no volume gain after hours | Raise ambient temp (75–78°F ideal), use proofing box or oven with light |

| Temperature Too Hot | Rapid rise followed by collapse, sour flavor | Cool environment; ferment in fridge for part of bulk or final proof |

Shaping Technique: Building Tension Matters

Even with perfect fermentation, poor shaping can doom your loaf. The goal is to create surface tension that helps the dough hold its shape and rise upward rather than slump sideways.

Common mistakes include rushing the preshape, skipping bench rest, or not tightening the surface enough during final shaping. A loose, slack-shaped boule will spread uncontrollably during proofing and baking.

Step-by-Step Shaping Process

- Preshape: Gently round the dough into a tight ball, pinching seams underneath. Rest uncovered for 20–30 minutes (bench rest).

- Final Shape: Flatten slightly, fold edges toward center, then roll tightly into a log or round boule.

- Create Tension: Use the edge of your hands and countertop to rotate the dough, sealing the seam and tightening the top surface.

- Seam Side Up: Place shaped loaf seam-side up in a floured banneton for proofing.

If your dough feels slack after shaping, practice tighter rolls and use less flour on the work surface—too much makes it hard to build grip.

“The shape you give your loaf before proofing is the blueprint for its final form. Respect the tension.” — Richard Bertinet, artisan baker and educator

Baking Factors That Affect Rise

Oven spring—the final burst of expansion when dough hits heat—is critical for height and crumb openness. Several baking conditions influence this phase.

Lack of steam is a frequent culprit. Steam keeps the crust flexible during the first 15–20 minutes of baking, allowing the loaf to expand fully. Without it, the crust hardens too soon, restricting rise.

Low oven temperature prevents rapid gas expansion. Always preheat your Dutch oven or baking steel for at least 45 minutes at 450–475°F (230–245°C). Sudden exposure to high heat shocks the yeast into one last burst of activity before they die off.

Poor scoring also limits expansion. Deep, decisive cuts (¼ to ½ inch deep) allow steam to escape in controlled ways, guiding where the loaf opens. Shallow or hesitant slashes won’t release pressure effectively, causing blowouts or uneven spreading.

Baking Checklist for Maximum Oven Spring

- Preheat oven and baking vessel for 45+ minutes

- Use steam: add ice cubes to a preheated tray, spritz dough, or cover with lid

- Score deeply and confidently before loading

- Bake covered for first 20–25 minutes, then uncover to finish browning

- Ensure internal temperature reaches 205–210°F (96–99°C) for full bake-out

Real Example: From Pancake Loaf to Perfect Rise

Sophie, a home baker in Portland, struggled for months with flat sourdough. Her starter was active, but her loaves consistently spread out in the Dutch oven, yielding dense, crepe-like results.

She reviewed her process and identified three issues: she was skipping the bench rest during shaping, proofing at room temperature overnight (about 12 hours), and scoring too shallowly. After adjusting, she implemented 30-minute bench rests, reduced final proof to 3.5 hours (using a thermometer to monitor temp), and practiced deeper scoring angles.

Her next loaf rose nearly two inches higher and had an open, airy crumb. “I realized I was letting the dough do all the work without giving it structure,” she said. “Once I took shaping seriously, everything changed.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my sourdough loaf spread after I score it?

This typically indicates overproofing or inadequate shaping tension. The dough has already expanded as much as it can, so scoring releases trapped gas and causes collapse. Try shortening your final proof or improving surface tension during shaping.

Can I save a flat sourdough loaf?

If caught before baking, an overproofed loaf can sometimes be reshaped and given a shorter second proof (1–2 hours). However, severely degraded gluten won’t recover. For future batches, adjust timing and temperature.

Does flour type affect loaf height?

Yes. High-protein bread flour (12–14% protein) supports better structure than all-purpose or whole grain flours. If using whole wheat or rye, blend with bread flour (e.g., 70% white, 30% whole) to maintain rise potential.

Conclusion: Turn Failure Into Mastery

Flat sourdough bread is frustrating, but it’s also instructive. Each collapsed loaf reveals something about your technique—whether it’s starter management, fermentation control, shaping finesse, or baking precision. The beauty of sourdough lies in its feedback loop: observe, adjust, repeat.

Keep a baking journal. Note starter feed times, dough temperatures, bulk fermentation duration, proof length, and oven settings. Over time, patterns emerge, and consistency improves. Don’t aim for perfection—aim for progress.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?