In June 2023, the world watched in horror as news broke: the Titan submersible, en route to view the wreck of the RMS Titanic, had gone missing. Days later, debris was found near the wreck site—confirmation that the vessel had suffered a catastrophic implosion. But why did it happen? What physical forces caused such a sudden and violent destruction? This article breaks down the science behind the implosion in plain language, exploring the crushing power of deep-ocean pressure, material limitations, and engineering challenges.

The Crushing Force of Deep-Sea Pressure

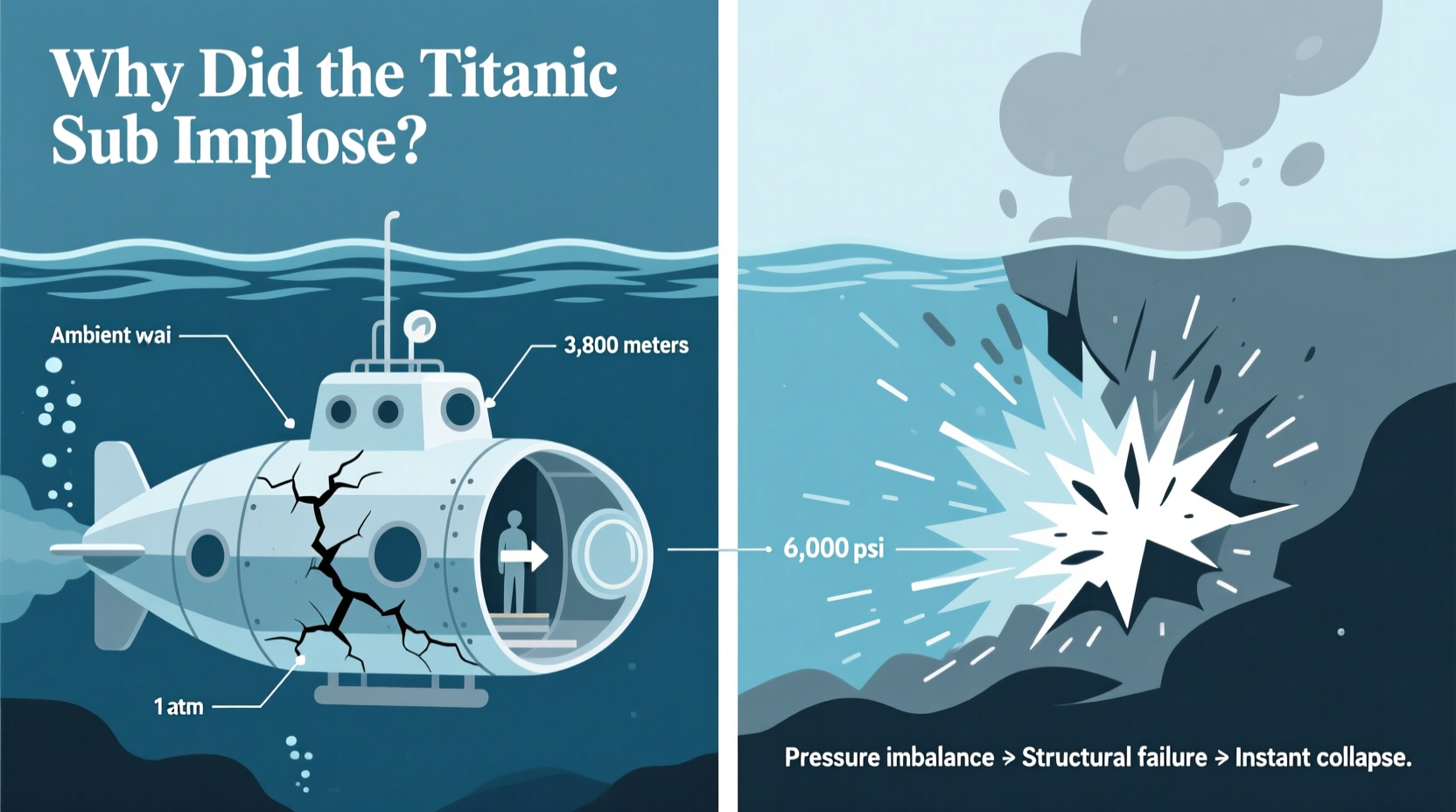

At the ocean’s surface, we live under one atmosphere of pressure—about 14.7 pounds per square inch (psi). As you descend underwater, pressure increases rapidly: for every 33 feet (10 meters) of depth, an additional atmosphere of pressure is added. The Titanic wreck lies approximately 12,500 feet (3,800 meters) below sea level. At that depth, the pressure exceeds 6,000 psi—over 400 times greater than at the surface.

This means that every square inch of a submersible’s hull must resist more than four tons of force. To visualize this, imagine stacking two small cars on every postage-stamp-sized area of the vessel. If the structure fails even slightly, the surrounding water doesn’t just seep in—it violently collapses the entire vehicle in milliseconds.

Unlike explosions, which push outward, implosions occur when external pressure overwhelms internal strength, causing a rapid inward collapse. In the case of Titan, the immense hydrostatic pressure outside the cabin exceeded the structural integrity of the vessel, triggering a near-instantaneous implosion.

How Materials Behave Under Extreme Pressure

The Titan submersible used a cylindrical carbon fiber composite hull capped with titanium hemispheres. While carbon fiber is strong and lightweight, its behavior under constant compressive stress differs significantly from metals like steel or titanium. Carbon fiber excels in tension but is more vulnerable to compression fatigue and delamination over time—especially when subjected to repeated deep dives.

Moreover, composite materials can suffer from \"microcracking\" due to cyclic loading—the process of descending and ascending through changing pressures. These tiny cracks are nearly invisible but grow with each dive, weakening the overall structure. Once a critical threshold is reached, failure becomes inevitable.

Titan’s design also raised concerns among experts because it combined dissimilar materials: carbon fiber and titanium. These expand and contract at different rates under temperature and pressure changes, potentially creating stress points where the two materials meet. Over time, this mismatch could lead to joint failure or buckling.

“Composite materials require extremely rigorous testing and certification for deep-sea use. There’s no room for guesswork when human lives depend on millimeter-thick walls holding back thousands of pounds per square inch.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Oceanographic Engineer, MIT

The Physics of Implosion: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

An implosion isn’t a slow leak or gradual sinking—it’s a sudden, total structural collapse occurring in less than a second. Here's how it unfolds physically:

- Pressure Differential Builds: As the sub descends, external water pressure rises exponentially while internal cabin pressure remains at roughly one atmosphere.

- Stress Accumulates: The hull experiences compressive stress across its surface. Any weak point—such as a seam, crack, or flawed section—begins to deform.

- Buckling Initiation: When stress exceeds the material’s yield strength, the hull begins to buckle inward. This creates a localized failure point.

- Cascading Collapse: Once deformation starts, pressure focuses on the weakest area, accelerating inward collapse. The surrounding structure cannot compensate fast enough.

- Total Implosion: Within milliseconds, the entire cabin collapses inward. Water rushes in at supersonic speeds relative to the shrinking volume, releasing energy comparable to several kilograms of TNT.

Survival is impossible. The event happens faster than nerve signals travel in the human body—passengers would not have felt pain or even realized what happened.

Design Flaws and Warning Signs

Multiple red flags were raised about Titan’s design before the fatal dive. Unlike most deep-sea submersibles certified by marine safety organizations, Titan was not independently reviewed or classified by bodies like DNV or ABS. Its experimental nature meant it operated outside standard safety frameworks.

One major concern was the use of a viewport made of acrylic—a material weaker than metal and prone to cracking under high cyclic stress. Acrylic viewports are common in shallow-diving subs but rare at depths beyond a few thousand feet. At 12,500 feet, the acrylic window would experience extreme stress, especially if scratched or improperly mounted.

Additionally, OceanGate, the company operating Titan, reportedly ignored warnings from former employees and industry experts. In 2018, a senior engineer resigned after raising concerns about the carbon fiber hull’s reliability. Another report indicated that internal sensors designed to monitor hull integrity had been disabled due to “excessive false alarms”—a decision that may have removed crucial early warning systems.

| Factor | Risk Level | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Fiber Hull | High | Poor performance under sustained compressive load; risk of delamination |

| Acrylic Viewport | High | Limited fatigue resistance at extreme depths |

| No Independent Certification | Critical | Lack of third-party validation increases unknown risks |

| Disabled Monitoring Systems | Severe | Removed ability to detect early signs of structural stress |

| Limited Test Dive History | Moderate | Few real-world validations of long-term durability |

Mini Case Study: The Fate of the Titan Submersible

On June 18, 2023, Titan departed from a support ship near Newfoundland, beginning its descent to the Titanic wreck. Communication was lost after approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes—just as the sub should have reached its target depth. Search teams launched a massive international effort when the scheduled surfacing time passed with no contact.

Five days later, a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) discovered a debris field on the seafloor, including the sub’s landing frame and pieces of the carbon fiber hull. The pattern of fragmentation indicated a high-energy implosion rather than mechanical failure or collision.

Forensic analysis of the wreckage suggested that the failure likely originated at the interface between the carbon fiber cylinder and one of the titanium end caps—or possibly at the viewport. The mismatch in material behavior under pressure, combined with potential pre-existing damage from prior dives, created a perfect storm for structural collapse.

This tragic event underscores the unforgiving nature of deep-ocean exploration. Unlike aviation or space travel, where failures may allow for emergency procedures, deep-sea implosions offer zero margin for error—and no second chances.

Safety Checklist for Deep-Sea Exploration Technology

While commercial deep-sea tourism remains rare, future ventures must prioritize proven engineering principles. Here’s a checklist any credible deep-submergence program should follow:

- ✅ Use only materials tested and certified for full-ocean-depth applications

- ✅ Conduct regular non-destructive testing (e.g., ultrasound, CT scans) on pressure vessels

- ✅ Ensure all components undergo fatigue analysis for repeated dive cycles

- ✅ Maintain redundant communication and tracking systems

- ✅ Require independent third-party certification from recognized maritime agencies

- ✅ Implement real-time structural health monitoring during dives

- ✅ Limit passenger missions until extensive unmanned testing is completed

Frequently Asked Questions

Could the passengers have survived the implosion?

No. An implosion at that depth occurs in microseconds—faster than the human brain can process sensory input. Death would have been instantaneous and painless.

Why didn’t they use a steel or titanium hull like other deep-sea subs?

Steel and titanium are heavier and more expensive, but they’re far more predictable under pressure. OceanGate opted for carbon fiber to reduce cost and weight, prioritizing innovation over proven reliability. This trade-off proved fatal.

Have there been other submersible implosions?

Yes, though rare. In 1963, the U.S. Navy’s Trieste II experienced a partial implosion during a test dive, leading to major redesigns. More recently, unmanned vehicles have failed due to pressure breaches, but crewed implosions are exceptionally uncommon—making Titan a stark outlier in modern times.

Lessons Learned and the Future of Deep-Sea Travel

The loss of the Titan submersible has sparked global debate about regulation in private deep-sea exploration. Unlike commercial aviation or offshore drilling, deep-ocean tourism operates in a largely unregulated space. Companies can legally build and operate experimental vessels without mandatory oversight—provided they obtain informed consent from passengers.

But informed consent cannot replace engineering rigor. No amount of liability waiver can mitigate flawed physics. As one marine safety expert put it: “You can sign all the waivers you want, but Archimedes’ principle still applies.”

Moving forward, the industry must adopt stricter standards. This includes mandatory certification, transparent design reviews, and limits on novel materials in life-critical structures. Public fascination with deep-sea wrecks shouldn’t override fundamental safety protocols.

Conclusion: Respecting the Power of Nature

The implosion of the Titan submersible was not a mystery of fate—it was a consequence of physics. The ocean, particularly at its deepest points, exerts forces so immense that even the smallest miscalculation can lead to disaster. While human curiosity drives us to explore these frontiers, we must do so with humility, precision, and respect for the laws of nature.

Advancements in technology should never outpace safety. The tragedy serves as a sobering reminder: in the deep ocean, silence isn’t peace—it’s pressure waiting to equalize. And when it does, it does so without warning.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?