The 1997 Kyoto Protocol was a landmark international agreement designed to combat global climate change by setting binding greenhouse gas emission reduction targets for industrialized nations. While 192 countries eventually ratified the treaty, one of the world’s largest emitters— the United States—never did. This decision has had profound implications for global climate policy and America’s environmental leadership. Understanding why the U.S. rejected the Kyoto Protocol requires examining a complex mix of political resistance, economic concerns, and diplomatic disagreements that continue to shape climate debates today.

Political Opposition and Senate Resistance

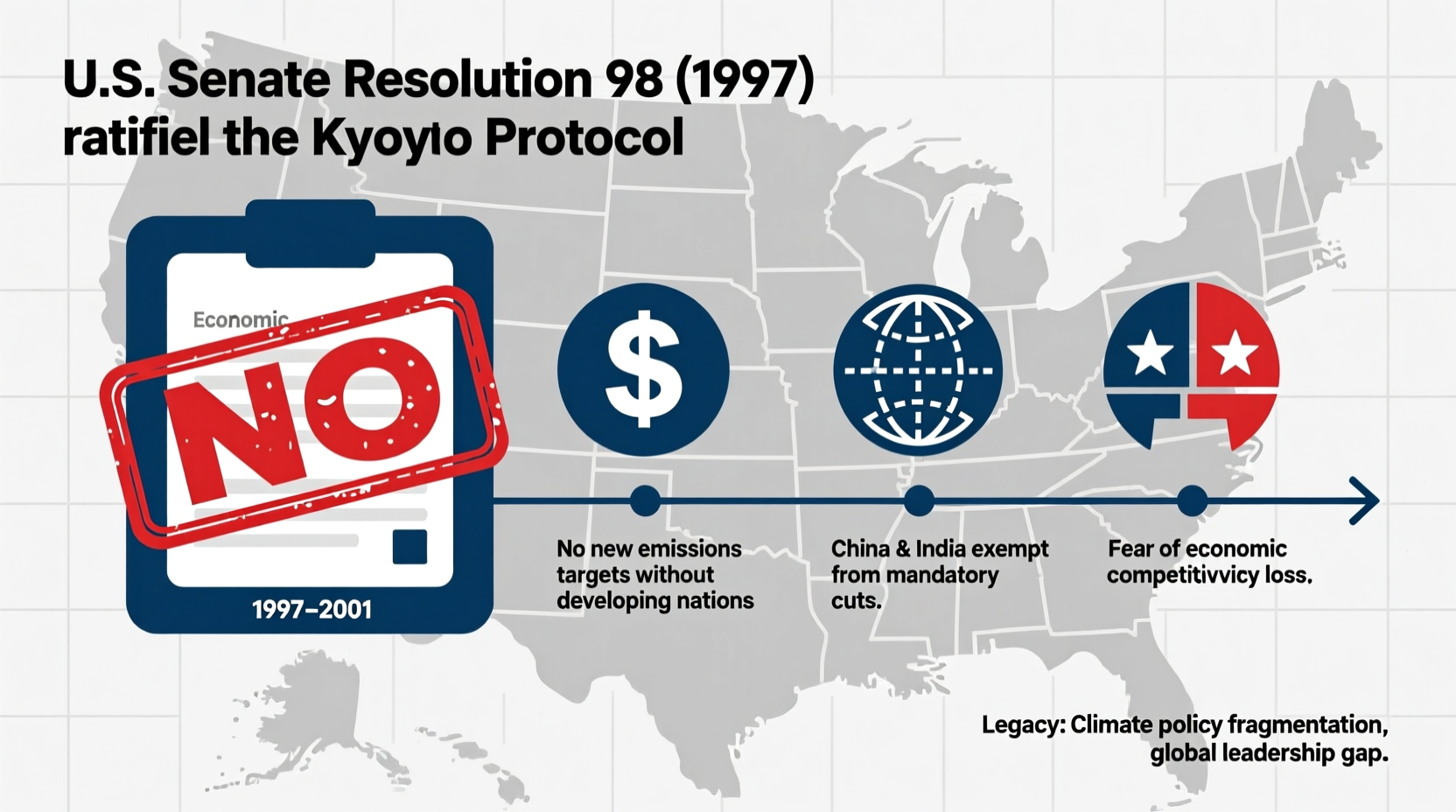

Even before the Kyoto Protocol was finalized, strong political opposition emerged in the United States. In 1997, the U.S. Senate passed the Byrd-Hagel Resolution (S. Res. 98) by a unanimous 95–0 vote. This resolution declared that the Senate would not ratify any climate treaty that either:

- Imposed mandatory emissions reductions on developed countries without requiring the same of developing nations like China and India,

- Threatened to harm the U.S. economy.

The resolution reflected bipartisan concern that the treaty would place an unfair burden on American industries while allowing rapidly growing economies to emit freely. Senator Robert Byrd (D-WV), a key sponsor, argued that “the developing nations must be required to participate” for any agreement to be effective or equitable.

“We cannot sacrifice our economy on the altar of unproven science and unequal obligations.” — Senator Chuck Hagel (R-NE), co-sponsor of the Byrd-Hagel Resolution

This early rejection signaled deep skepticism within Congress about the fairness and feasibility of the Kyoto framework, effectively boxing in future administrations regardless of party affiliation.

Economic Concerns and Industry Influence

A central argument against ratification was the perceived threat to American economic competitiveness. At the time, the U.S. was responsible for approximately 25% of global carbon emissions despite having only 4% of the world’s population. The Kyoto Protocol required the U.S. to reduce emissions to 7% below 1990 levels by 2012—a significant challenge for an economy heavily reliant on fossil fuels.

Energy-intensive sectors—including coal, manufacturing, and transportation—warned of job losses, higher energy prices, and reduced industrial output. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and various trade associations launched aggressive lobbying campaigns, arguing that compliance would cost hundreds of thousands of jobs and billions in GDP.

These fears were amplified during periods of economic uncertainty, making it politically risky for leaders to champion what opponents framed as a “job-killing” treaty. Even environmentally conscious policymakers hesitated to back a measure so strongly opposed by labor and industry groups.

Diplomatic Disputes Over Fairness and Participation

One of the most persistent criticisms of the Kyoto Protocol was its differentiation between developed and developing countries. Under the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities,” nations like China, India, and Brazil faced no binding emissions targets, despite their rising contributions to global pollution.

By 2000, China had become the second-largest emitter of CO₂ after the U.S., yet it remained exempt from mandatory cuts. This exemption became a major sticking point in Washington. Policymakers argued that any effective climate agreement must include all major emitters, especially those experiencing rapid industrialization.

The lack of reciprocal commitments undermined the treaty’s credibility in American eyes. As President George W. Bush stated in 2001 when announcing the U.S. withdrawal from Kyoto:

“The nation that leads the world in emissions should not be the only one bound by mandatory targets. Developing nations must also take on measurable responsibilities.” — President George W. Bush, March 2001

This stance highlighted a fundamental shift in U.S. climate diplomacy—one that prioritized universal participation over historical responsibility.

Legacy of the Decision: Long-Term Impacts

The failure of the U.S. to ratify the Kyoto Protocol left a lasting imprint on global climate governance. Though the treaty entered into force in 2005 without U.S. participation, its effectiveness was significantly weakened. The absence of the world’s largest economy diminished momentum, investment, and technological cooperation.

Moreover, the U.S. position influenced other reluctant nations and set a precedent for conditional engagement in future agreements. However, this legacy is not entirely negative. The shortcomings of Kyoto informed the design of the 2015 Paris Agreement, which adopted a more flexible, bottom-up approach with voluntary national pledges (NDCs) from nearly every country—including major developing economies.

The U.S. initially joined the Paris Agreement under President Obama, withdrew under President Trump, and rejoined under President Biden—demonstrating how domestic politics continue to shape international climate commitments.

| Climate Agreement | U.S. Status | Key Difference from Kyoto |

|---|---|---|

| Kyoto Protocol (1997) | Not ratified | Binding targets only for developed nations |

| Paris Agreement (2015) | Ratified, then withdrawn, then rejoined | Voluntary pledges from all countries |

Mini Case Study: California’s Subnational Leadership

In the absence of federal action post-Kyoto, some U.S. states took initiative. California, for example, passed the Global Warming Solutions Act (AB 32) in 2006, establishing its own cap-and-trade program and committing to reduce emissions to 1990 levels by 2020.

This state-level effort demonstrated that climate action could succeed without federal mandates. By 2020, California had met its target—proof that subnational actors can drive progress even amid national gridlock. Other states followed with regional compacts like the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI).

Step-by-Step: How the U.S. Engaged With Kyoto Over Time

- 1997: U.S. signs the Kyoto Protocol under President Clinton, but does not submit it for Senate ratification due to Byrd-Hagel Resolution.

- 2001: President George W. Bush formally announces the U.S. will not implement the treaty, citing economic and fairness concerns.

- 2005: Kyoto enters into force internationally; U.S. remains outside the agreement.

- 2009: President Obama expresses support for climate action but focuses on domestic legislation (e.g., Waxman-Markey bill), which fails in the Senate.

- 2015: U.S. pivots to the Paris Agreement, learning from Kyoto’s top-down model to advocate for broader participation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did the U.S. ever sign the Kyoto Protocol?

Yes, the U.S. signed the Kyoto Protocol in 1998 under President Bill Clinton. However, signing is not the same as ratifying. The treaty was never submitted to the Senate for approval, so it never became legally binding for the U.S.

Was the science behind climate change disputed in the U.S. decision?

While some officials questioned the certainty of climate models at the time, the primary objections were economic and diplomatic—not scientific denial. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and major scientific bodies acknowledged climate change as real and human-caused even in the late 1990s.

Has the U.S. done anything meaningful on climate since rejecting Kyoto?

Yes. Despite rejecting Kyoto, the U.S. has implemented various environmental regulations, invested in renewable energy, and participated in later accords like the Paris Agreement. Many cities, states, and corporations have also adopted ambitious climate goals independently.

Conclusion: Learning From the Past to Shape the Future

The U.S. decision not to ratify the Kyoto Protocol was rooted in legitimate concerns about economic impact, global equity, and enforceability. While criticized internationally, it underscored the need for inclusive, adaptable frameworks that balance environmental urgency with political realism.

The legacy of Kyoto serves as both a cautionary tale and a catalyst for improvement. It reminds us that even well-intentioned global agreements can falter without broad buy-in. Today’s climate strategies must account for diverse national circumstances, engage all major emitters, and build resilient coalitions across governments, businesses, and communities.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?