When a honeybee stings, it often pays with its life. This dramatic act of self-sacrifice is not just a curious biological oddity—it’s a finely tuned defense mechanism shaped by millions of years of evolution. Unlike wasps or hornets, which can sting repeatedly without harm, the honeybee’s sting is a one-time event that ends in death. To understand why, we need to explore the intricate anatomy of the bee’s stinger, the mechanics of stinging, and the evolutionary trade-offs that make this fatal act beneficial for the hive as a whole.

The Anatomy of a Bee’s Stinger

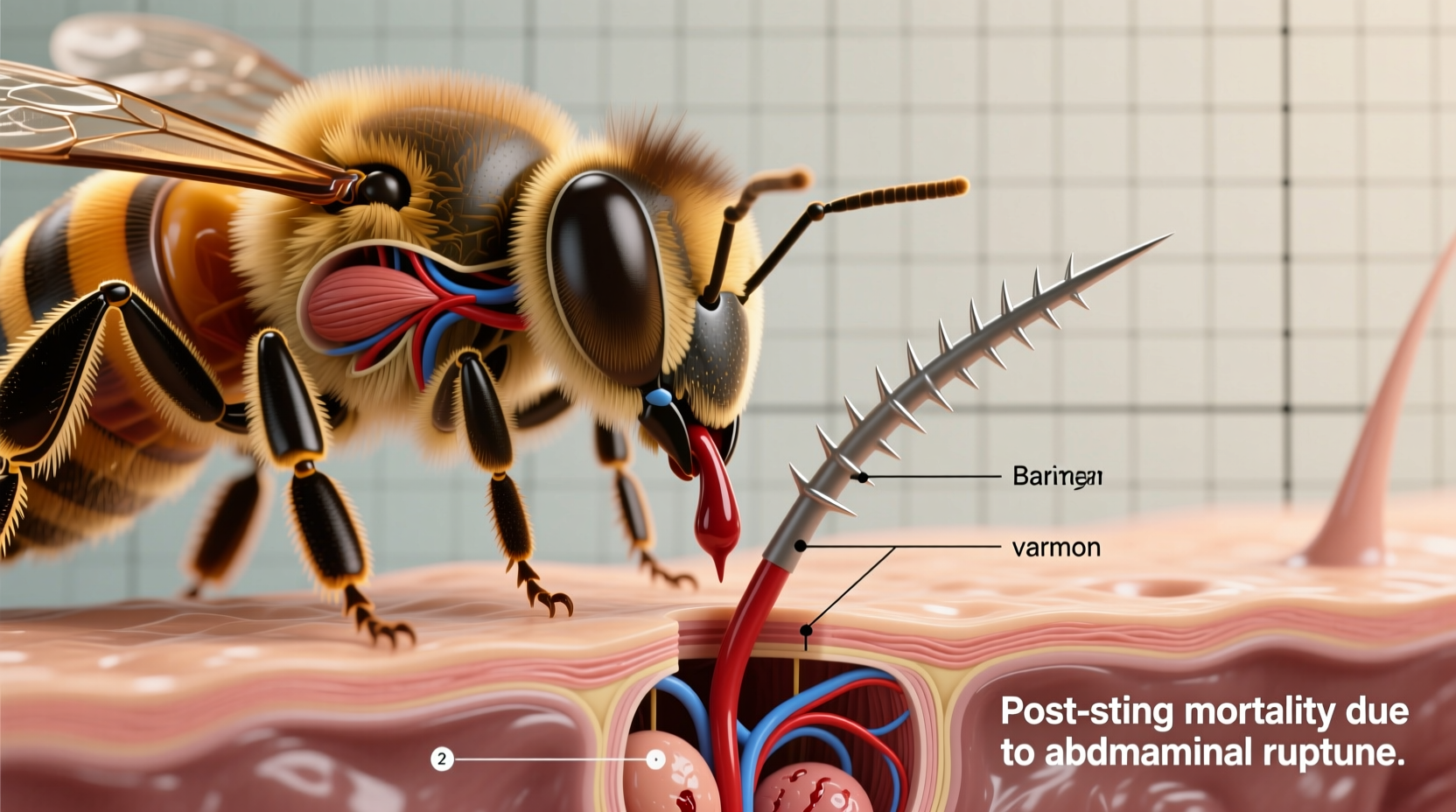

The honeybee stinger is a complex organ designed primarily for defense. It consists of three main parts: two barbed lancets and a central stylet. These components work together like a drill, enabling the stinger to penetrate skin and deliver venom. The barbs on the lancets are key to understanding why the bee dies after stinging mammals.

When a honeybee stings a human or other mammal, the barbs catch in the elastic skin. As the bee attempts to fly away, the stinger becomes lodged. The force of flight pulls the stinger—and much more—out of the bee’s body. What follows is not just the loss of a defensive tool but a catastrophic rupture of internal organs.

What Gets Left Behind?

It's not just the stinger that remains embedded. Attached to it are:

- The venom sac, which continues to pump toxins into the wound

- Part of the digestive tract

- Muscles that control the stinger’s movement

- Nerves and ganglia responsible for venom delivery

This extensive tissue detachment causes massive abdominal rupture. The bee essentially eviscerates itself, leading to rapid death within minutes. In contrast, when bees sting other insects—whose exoskeletons are harder and less elastic—the barbs don’t get caught, allowing the bee to withdraw the stinger safely and survive.

Evolutionary Trade-Off: Sacrifice for the Hive

At first glance, dying after a single sting seems like a poor survival strategy. But from an evolutionary perspective, it makes perfect sense. Honeybees are social insects, and their primary goal is not individual survival but the protection of the colony.

By sacrificing themselves, guard bees ensure that intruders—especially mammals like bears or humans who might raid the hive for honey—are deterred. The persistent pumping of venom even after death increases pain and inflammation, making future attacks less likely. This delayed defense mechanism amplifies the impact of a single sting.

“Honeybee stinging is one of the clearest examples of altruistic behavior in nature. The individual dies, but the genetic legacy lives on through the queen and her offspring.” — Dr. Alan Molumby, Entomologist, University of Illinois

Why Barbs Evolved in Honeybees

Barbed stingers are unique to honeybees among common stinging insects. Wasps and bumblebees have smooth stingers, allowing them to sting multiple times. So why did honeybees evolve such a deadly design?

The answer lies in predator pressure. Early ancestors of modern honeybees faced significant threats from vertebrate predators. A stinger that anchors into soft tissue ensures maximum venom delivery and increases the chance of deterring large animals. Over time, natural selection favored bees with more effective (and thus more barbed) stingers—even if it meant certain death upon use.

Sting Mechanics: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

The process of stinging and dying unfolds rapidly. Here’s what happens during a typical defensive sting:

- Threat Detection: Guard bees detect vibrations, scents, or physical contact indicating danger near the hive.

- Attack Initiation: The bee positions itself and drives its stinger into the target’s skin.

- Barb Engagement: The backward-facing barbs hook into the elastic dermis, anchoring the stinger.

- Detachment: As the bee tries to flee, abdominal tissues tear, leaving the stinger, venom sac, and associated organs embedded.

- Continued Venom Delivery: Muscles in the detached apparatus contract rhythmically, injecting venom for up to 20 minutes post-sting.

- Bee Mortality: The bee suffers fatal internal injuries and dies shortly after, unable to feed or function.

This autonomous venom delivery system turns the stinger into a “miniature drone weapon,” continuing the defense even after the bee’s death.

Do All Bees Die After Stinging?

No. The fatal sting is specific to adult female worker honeybees (Apis mellifera). Other species behave differently:

| Species | Can Sting Multiple Times? | Stinger Type | Fatal After Sting? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Honeybee (Worker) | No | Barbed | Yes |

| Bumblebee | Yes | Smooth | No |

| Wasp (e.g., Yellow Jacket) | Yes | Smooth | No |

| Hornet | Yes | Smooth | No |

| Queen Honeybee | Limited (rarely stings) | Slightly barbed | Usually survives |

Note: While queen honeybees possess stingers, they rarely use them outside of battling rival queens. Their stingers are less barbed than workers’, allowing potential reuse.

Real Example: A Bear Attacks a Hive

In a documented case in rural Montana, a black bear attempted to raid a wild honeybee colony. Within seconds, dozens of guard bees swarmed the bear’s face and paws. Each sting injected venom and became lodged, causing immediate pain and swelling.

The bear retreated after less than a minute, despite having accessed only a small portion of the hive. Autopsies of the dead bees found near the site confirmed complete abdominal eversion—clear evidence of fatal stinging. The sacrifice of approximately 50 bees successfully protected thousands of colony members and preserved vital food stores. This illustrates how individual mortality translates into collective survival.

How to Respond When Stung

If you’re stung by a honeybee, prompt action can minimize pain and reduce venom absorption. Follow this checklist:

- ✅ Scrape the stinger out immediately using a fingernail or credit card—do not pinch it with tweezers, as this squeezes more venom in.

- ✅ Wash the area with soap and water to prevent infection.

- ✅ Apply a cold compress to reduce swelling.

- ✅ Use over-the-counter antihistamines or hydrocortisone cream to relieve itching.

- ✅ Monitor for signs of allergic reaction: difficulty breathing, hives, dizziness.

- ✅ Seek emergency care if anaphylaxis is suspected.

Removing the stinger quickly stops further venom injection. Studies show that delaying removal by just 30 seconds significantly increases toxin load.

Debunking Common Myths

Several misconceptions surround bee stings and bee biology. Let’s clarify a few:

- Myth: Bees choose to die when they sting.

Truth: Death is an unavoidable anatomical consequence, not a conscious decision. - Myth: All bees die after stinging.

Truth: Only honeybee workers die; bumblebees and wasps can sting repeatedly. - Myth: The bee explodes when it stings.

Truth: The bee doesn’t explode—it undergoes traumatic abdominal rupture due to tissue detachment. - Myth: Dead bees release a scent that calms others.

Truth: Actually, the opposite: alarm pheromones from the venom attract more bees to attack.

Understanding these facts helps dispel fear and promotes coexistence with these essential pollinators.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why don’t wasps die after stinging?

Wasps have smooth stingers without barbs. This allows them to pierce and retract the stinger cleanly from both insect and mammalian skin. Their evolutionary path didn’t favor barbed stingers because they use stings for hunting prey as well as defense, requiring multiple uses.

Can a bee sting without dying?

Yes—but only under specific conditions. If a honeybee stings another insect with a hard exoskeleton, the barbs don’t catch, and the stinger can be withdrawn. However, stinging any animal with elastic skin (like humans or mammals) almost always results in fatal injury.

Is there a way to save a bee after it stings?

No. Once the stinger and internal organs are torn from the abdomen, the bee cannot survive. The damage is irreversible, and the bee will die within minutes regardless of intervention.

Conclusion: Honoring the Hive’s Guardians

The fatal sting of the honeybee is a powerful reminder of nature’s balance between individual cost and collective benefit. What appears to be a flaw—an inability to survive after defending the hive—is actually a highly refined adaptation that enhances the survival of the entire colony. Each sting is a final act of loyalty, ensuring that future generations of bees can thrive.

Next time you hear the buzz of a bee, remember: it’s not looking to harm you. It’s simply trying to protect its home. By understanding the biology behind the sting, we foster greater respect for these vital pollinators and make informed choices to avoid unnecessary conflict.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?