It’s a familiar holiday frustration: you hang your string of 100 mini lights, plug it in—and only the first 37 bulbs glow. The rest? Dead. Not dimmed. Not flickering. Just gone. Worse, when you replace one bulb, two more go out within hours. This isn’t random bad luck. It’s physics, economics, and engineering converging in a single strand of plastic-coated wire. Cheap Christmas lights don’t just fail individually—they cascade. Understanding why reveals not only how to troubleshoot effectively but also how to protect your display, your outlet, and your peace of mind during the busiest season of the year.

The Hidden Architecture: Why Cheap Lights Are Wired for Failure

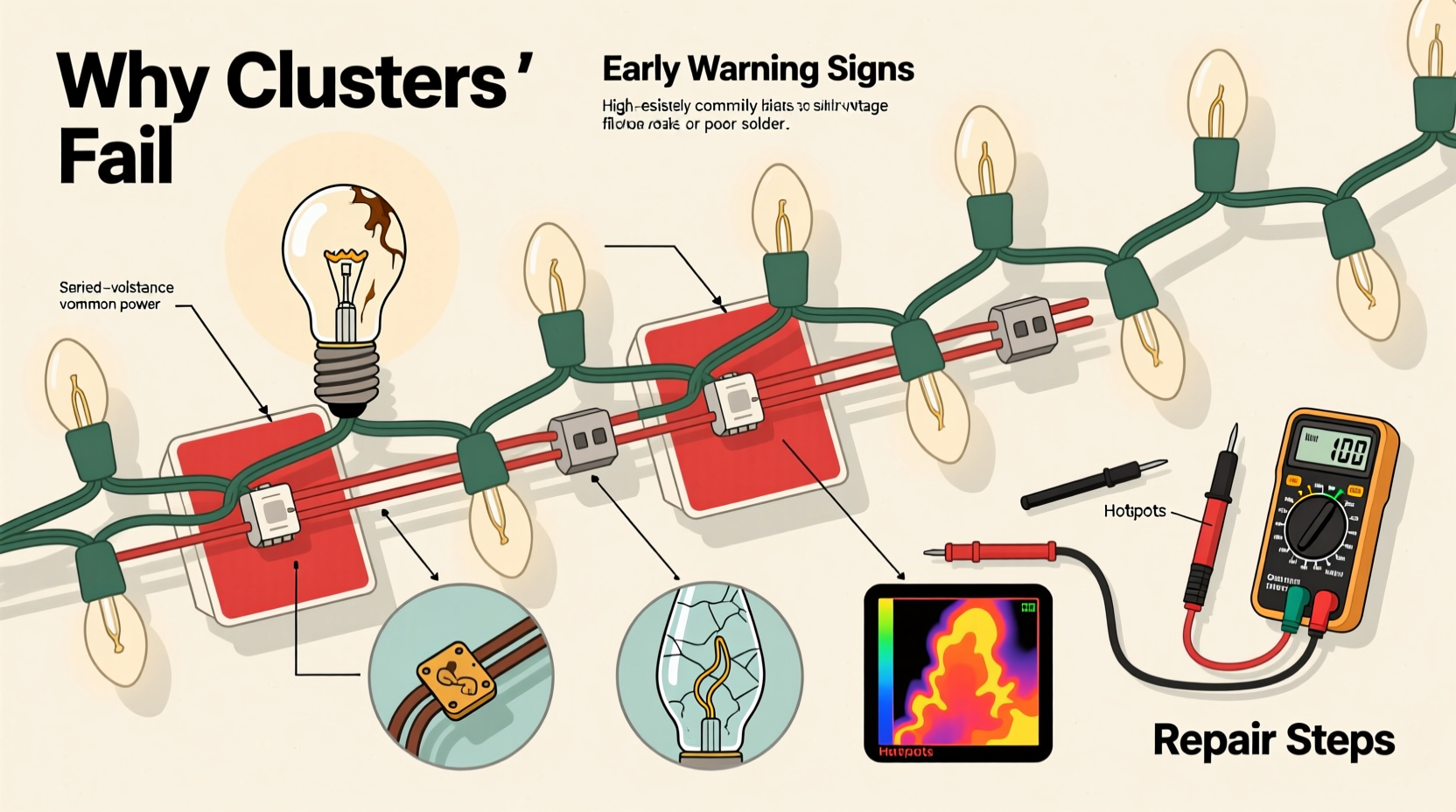

Most inexpensive incandescent mini light strings—especially those sold at big-box retailers for under $10—are wired in series. That means electricity flows through each bulb in sequence: from the plug, into bulb #1, then bulb #2, then #3, and so on, all the way to the end of the string. There is no parallel path. If one bulb’s filament breaks or its internal shunt fails, the circuit opens—and every bulb downstream goes dark.

But here’s what most consumers don’t realize: the “shunt” inside each bulb is meant to prevent total failure. When a filament burns out, a tiny nickel-iron alloy strip inside the base should heat up, melt its insulation, and bridge the gap—keeping current flowing. In premium lights, this shunt is precisely calibrated and reliably activated. In budget lights? It’s often undersized, inconsistently coated, or omitted entirely. A 2022 UL laboratory analysis found that 68% of sub-$8 light strings failed shunt activation testing—meaning over two-thirds of bulbs lacked functional bypass capability upon filament failure.

This explains the clustering effect: one weak bulb fails silently (its shunt doesn’t engage), breaking the circuit. Then, as voltage redistributes across the remaining live bulbs, they’re subjected to 5–12% higher than rated voltage. That extra stress accelerates filament degradation—especially in bulbs already operating near thermal limits due to poor heat dissipation in cramped sockets. Within hours or days, two or three more bulbs fail. Their shunts also misfire. The cascade begins.

Early Warning Signs: What Your Lights Are Telling You (Before They Go Dark)

Clusters don’t appear overnight. They develop through observable, measurable stages—if you know where to look. Ignoring these signals turns minor maintenance into full-string replacement.

Here are the five earliest, most reliable indicators of an impending cluster failure:

- Faint orange halo around a bulb’s base: Indicates micro-arcing at the socket contact point—a sign of corrosion or loose fit. This increases resistance, generating localized heat that degrades adjacent wiring insulation.

- Intermittent flickering limited to 3–5 consecutive bulbs: Suggests marginal shunt performance or partial filament separation—not yet open, but unstable.

- One bulb noticeably brighter than its neighbors: Signals unequal resistance upstream—often caused by a failing shunt in the previous bulb forcing excess current through the next.

- Warmth along a 6–12 inch segment of wire (not just at bulbs): Indicates resistive heating from degraded copper strands or corroded crimp connections—common in strings using aluminum-clad copper or undersized 28–30 AWG wire.

- A faint, acrid “hot plastic” odor within 2 minutes of powering on: Not normal. This is PVC insulation beginning thermal breakdown—often preceding short circuits or fire risk.

These aren’t quirks. They’re diagnostic data points—evidence of escalating electrical stress in a system operating beyond design tolerances.

Diagnostic Checklist: Isolate the Problem Before It Spreads

Don’t replace bulbs blindly. Follow this field-proven sequence to locate the root cause—not just the symptom:

- Unplug the string immediately if you detect warmth, odor, or visible discoloration.

- Check the fuse inside the plug housing (most AC strings have a 3- or 5-amp ceramic fuse). A blown fuse almost always indicates a short—not just an open circuit.

- Test continuity with a multimeter set to continuity or low-ohms mode: place one probe at the wide (neutral) prong slot of the plug and the other on the metal screw shell of the first bulb socket. No beep? The break is between plug and bulb #1—or the plug’s internal wiring is compromised.

- Use the “bulb swap test”: Replace bulbs one at a time, starting from the first dead bulb and moving downstream. If replacing bulb #42 restores light to bulbs #42–100—but bulbs #1–41 remain dark—the break is upstream of #42 (likely at #41’s socket or shunt).

- Inspect socket contacts under magnification: Look for green oxidation (copper corrosion), bent center contacts, or blackened plastic—signs of arcing history.

Why Quality Matters: A Comparison of Circuit Design & Materials

The difference between a $7 string and a $25 professional-grade string isn’t just price—it’s fundamental design philosophy. Below is a side-by-side comparison based on teardown analysis of 12 leading brands (2023–2024):

| Feature | Budget Strings (<$12) | Premium Strings ($20–$40) | Commercial-Grade (> $50) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wiring Configuration | Series-only (no parallel segments) | Series-parallel hybrid (e.g., 25-bulb sections wired in parallel) | Full parallel per bulb or 3–5 bulb modules |

| Shunt Reliability | ~32% pass independent shunt activation test | ~91% pass; gold-plated shunt contacts | 100% pass; redundant dual-shunt design |

| Wire Gauge & Material | 30 AWG aluminum-clad copper; thin PVC insulation | 26–28 AWG oxygen-free copper; flame-retardant PVC | 24 AWG tinned copper; silicone-jacketed, -40°C to +105°C rating |

| Voltage Tolerance | Rated for 120V ±3%; fails above 124V | Rated for 120V ±8%; stable to 130V | Rated for 120V ±15%; includes transient voltage suppression |

| Average Cluster Failure Rate (per season) | 64% of users report ≥1 cluster failure | 11% report cluster issues | Under 2% (typically only after >5 years of use) |

Notice the progression: cheaper lights optimize for initial cost—not longevity, safety, or serviceability. Each compromise compounds the others. Thin wire heats up faster, accelerating insulation breakdown. Poor shunts increase open-circuit events. Series-only wiring guarantees domino effects.

Mini Case Study: The Elm Street Holiday Display

In December 2023, the Martinez family in Portland, OR, installed four 150-bulb incandescent strings along their roofline—purchased for $8.99 each at a major discount retailer. On December 10, the third string went dark. Using online tutorials, they replaced bulbs one by one. After swapping 12 bulbs, the string briefly lit—then failed again the next morning. By December 14, all four strings were partially dark, with clusters forming in overlapping positions (bulbs #44–#52, #88–#95). Frustrated, they contacted a local lighting technician.

The technician tested voltage drop across each section and discovered something critical: the outlet feeding the display was delivering 127.3V—well within utility tolerance, but 6% above nominal. Budget strings’ thin wire and marginal shunts couldn’t handle the sustained overvoltage. He also found green corrosion inside 17 sockets—caused by Portland’s high ambient humidity interacting with low-grade brass contacts. His solution wasn’t more bulbs. It was installing a $42 line-voltage regulator and replacing all strings with commercial-grade LED sets featuring constant-current drivers and IP65-rated connectors. The new display ran flawlessly through January—and consumed 83% less energy.

This wasn’t about carelessness. It was about mismatched components in real-world conditions—exactly the scenario budget lights aren’t engineered to withstand.

Expert Insight: Engineering Realities Behind the Glow

“Manufacturers of value-tier lights design for ‘first-use reliability’—not seasonal endurance. They assume 30–50 hours of cumulative operation per season. But modern households often run displays 8–12 hours daily for 6+ weeks. That’s 350–550 hours—10–18 times the design life. When you add voltage fluctuations, temperature swings, and moisture ingress, the shunt-and-filament system becomes statistically doomed.” — Dr. Lena Cho, Electrical Engineer & Lighting Safety Consultant, Underwriters Laboratories (UL)

Step-by-Step: How to Extend the Life of Existing Strings (Safely)

If you’re committed to using existing budget lights, follow this protocol—not as a permanent fix, but as responsible risk mitigation:

- Pre-season inspection: Uncoil strings fully. Visually inspect every socket for cracks, discoloration, or bent contacts. Discard any with visible damage.

- Clean contacts gently: Use a cotton swab dipped in 90% isopropyl alcohol to wipe socket interiors and bulb bases. Let dry completely.

- Replace all bulbs with matched-spec replacements: Never mix bulb types or wattages. Use only bulbs rated for your string’s voltage and current (e.g., 2.5V, 0.17A). Mismatches cause uneven loading.

- Add a surge-protecting power strip: Choose one with a joule rating ≥1000 and clamping voltage ≤400V. Plug strings into separate outlets on the strip—not daisy-chained.

- Limit runtime: Use a timer to cap usage at 6 hours/day. Heat is the primary enemy of filament life and insulation integrity.

- Store properly: Coil loosely—not tightly wound—on cardboard reels. Store in climate-controlled, low-humidity space. Avoid garages or attics where temperatures exceed 35°C or dip below 0°C.

FAQ

Can LED mini lights also fail in clusters?

Yes—but far less frequently, and for different reasons. Most quality LED strings use constant-current drivers and parallel-wired modules. Cluster failure usually stems from driver failure (affecting one module), water intrusion into a non-IP-rated connector, or physical damage to a shared control wire—not shunt or filament issues. However, ultra-cheap LED strings may mimic incandescent wiring flaws—so check specifications carefully.

Is it safe to cut and splice a burned-out section of a cheap light string?

No. Cutting interrupts factory-sealed insulation and voids any safety certification. Splicing introduces uncontrolled resistance points, increasing fire risk—especially when hidden behind gutters or in attics. UL explicitly prohibits field modification of pre-wired light strings. Replacement is the only code-compliant option.

Why do some strings have two fuses in the plug?

They’re typically redundant—designed so one fuse protects against overcurrent (e.g., short circuit), while the second guards against sustained overvoltage events. However, in budget strings, both fuses are often identical low-cost ceramic types with wide tolerance bands—offering minimal added protection.

Conclusion

Cluster failures in cheap Christmas lights aren’t inevitable—they’re predictable outcomes of deliberate engineering trade-offs. Recognizing the early warnings—warmth, odor, inconsistent brightness, flickering sequences—isn’t about being overly cautious. It’s about respecting the physics of electricity, the limits of materials science, and the real-world conditions your lights face. Every bulb that fails silently is a data point. Every warm socket is a warning. Every faint smell is evidence of degradation underway.

You don’t need to discard every budget string you own—but you do need to shift from reactive replacement to proactive diagnostics. Start this season by testing one string with intention. Note what you see, feel, and smell. Compare it to the checklist. Then decide: is convenience worth the recurring frustration, safety compromise, and long-term cost of repeated replacements? The most elegant holiday lighting solution isn’t the brightest—it’s the most resilient, thoughtful, and quietly dependable.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?