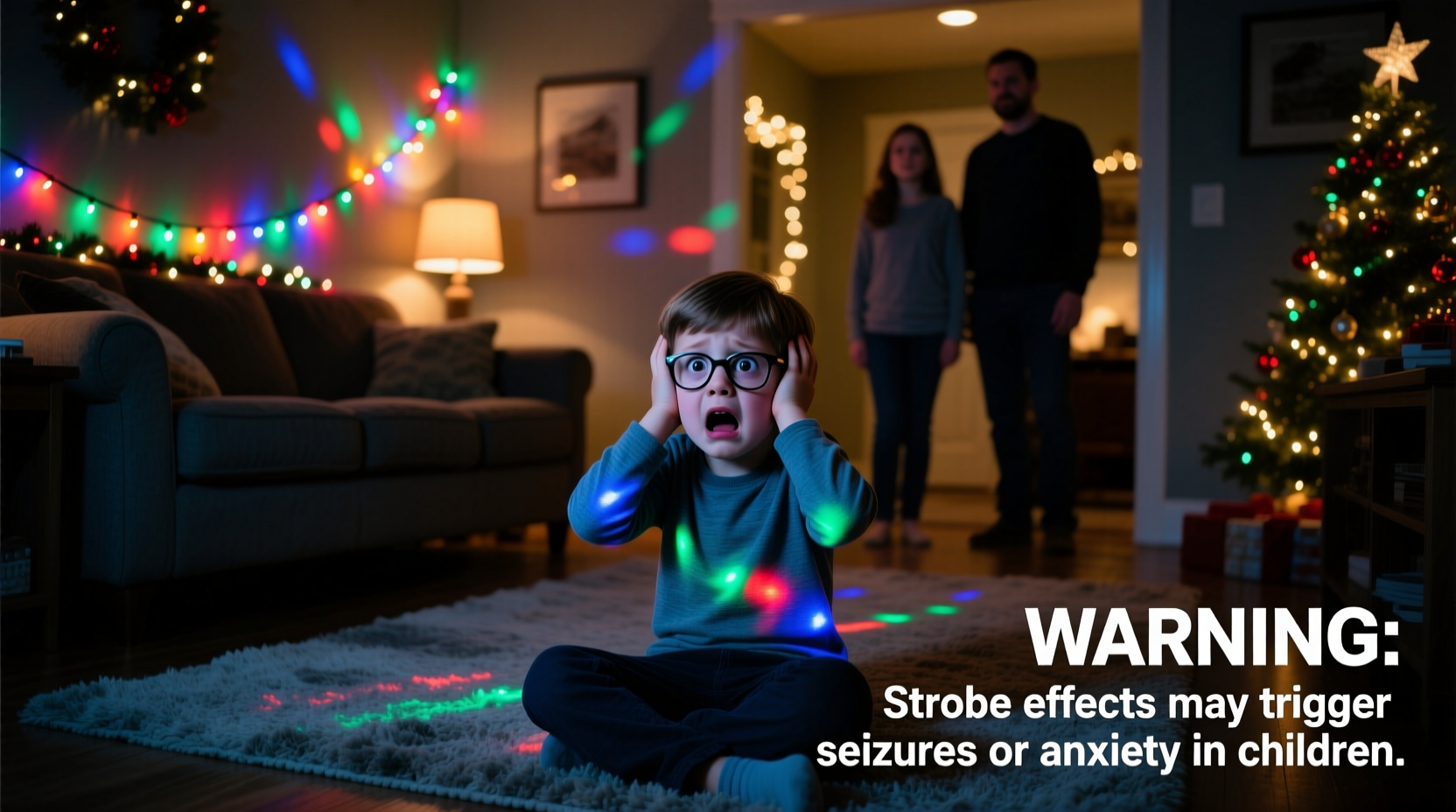

Every holiday season, festive displays dazzle with rapid flashes—twinkling LED strings, synchronized light shows, animated projections, and even smartphone-filtered videos featuring pulsing “disco” effects. While many adults find these effects charming or nostalgic, a subset of children respond with distress: sudden crying, covering their eyes, fleeing the room, clutching their heads, or even experiencing nausea or loss of balance. These reactions are not mere fussiness. They reflect real neurophysiological sensitivities—some benign and transient, others tied to clinically significant conditions. Understanding why children react strongly to strobe-like stimuli isn’t about limiting joy; it’s about enabling inclusion, preventing harm, and honoring neurological diversity in everyday environments.

The Neurological Basis: Why Strobe Effects Trigger Strong Reactions

Children’s developing visual and vestibular systems process rapid light changes differently than adult brains. The human visual cortex detects flicker up to approximately 60–90 Hz under ideal conditions—but sensitivity peaks earlier in life. Studies using electroencephalography (EEG) show that children aged 3–12 exhibit heightened photic driving responses: rhythmic brainwave entrainment to flashing lights at frequencies between 5–30 Hz. This neural synchronization can disrupt normal cortical processing, especially in regions governing attention, emotional regulation, and sensory integration.

Crucially, this sensitivity is amplified in children with certain neurodevelopmental profiles. Up to 3% of children have photosensitive epilepsy—a condition where specific visual patterns (including repetitive flashes, high-contrast stripes, or abrupt luminance shifts) can trigger seizures. But far more common—and often overlooked—are non-epileptic photic sensitivities. These include:

- Visual stress (also known as Meares-Irlen syndrome): A perceptual processing disorder causing glare, illusions of movement, or headaches under flickering or high-contrast lighting.

- Sensory processing disorder (SPD): Where the brain misinterprets or overresponds to sensory input, leading to fight-flight-freeze reactions to seemingly benign stimuli.

- Vestibulo-ocular reflex immaturity: In younger children, rapid visual motion can conflict with inner-ear signals, provoking dizziness or nausea—similar to motion sickness.

- Autism spectrum differences: An estimated 80–90% of autistic children experience sensory hyper-reactivity, with fluorescent or strobing lights cited as top environmental stressors in clinical surveys.

Importantly, these reactions are rarely “behavioral”—they’re physiological. A child who bolts from a decorated tree isn’t being defiant; they’re attempting self-preservation in response to an overwhelming neural signal.

Strobe Risk Spectrum: From Low-Risk Twinkles to High-Risk Hazards

Not all flashing lights carry equal risk. The danger depends on four interrelated factors: frequency (flashes per second), contrast (difference between brightest and darkest states), duration of exposure, and spatial pattern. Below is a comparative summary of common holiday lighting scenarios and their relative risk levels for sensitive children.

| Light Effect Type | Typical Flash Frequency | Risk Level | Key Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard “twinkle” LED string (mechanical timer) | 0.5–2 Hz (slow blink) | Low | Rarely problematic; may cause mild distraction in very young children. |

| Programmable RGB LED strip (fast chase or pulse mode) | 10–25 Hz | Moderate to High | Falls within peak photic driving range; high contrast amplifies risk. |

| Commercial light shows (e.g., drive-through displays) | Varies widely; often includes bursts at 15–20 Hz | High | Combined with music, motion, and scale—increases sensory load and disorientation. |

| Smartphone holiday filters (TikTok/Instagram strobe effects) | Often 10–30+ Hz, unregulated | Very High | Unintended exposure; no warning labels; close viewing distance intensifies effect. |

| Older incandescent “blinking” bulbs (thermal bimetallic switch) | ~1–1.5 Hz | Low | Slow, irregular rhythm minimizes neural entrainment risk. |

This table underscores a critical point: modern programmable LEDs—while energy-efficient and visually dynamic—pose greater neurological challenges than traditional lighting. Their precise, high-contrast, rhythmic pulses align closely with frequencies known to provoke cortical instability in susceptible children.

Real-World Impact: A Case Study from a Community Holiday Event

In December 2023, the Maplewood Elementary PTA hosted its annual “Winter Light Festival” in the school gymnasium. Organizers installed synchronized LED panels programmed to flash in time with holiday music—designed to create a “magical,” immersive atmosphere. Over 200 families attended, including many with children receiving occupational or behavioral therapy.

Within 12 minutes of the show’s start, three children exhibited acute distress: a 6-year-old with ADHD covered his ears and vomited; an 8-year-old diagnosed with sensory processing disorder began sobbing uncontrollably and hid beneath a bench; and a 5-year-old with a known history of absence seizures experienced a brief episode of unresponsiveness lasting 45 seconds—confirmed by school nurse observation and later EEG correlation.

Post-event review revealed that the lighting sequence included repeated 18-Hz pulses at >90% contrast, lasting 90-second cycles. No warning signage was posted, and staff had received no training on photic sensitivity. The PTA responded swiftly: they commissioned a lighting audit, added clear pre-entry warnings, introduced a “calm corner” with dimmed lighting and noise-canceling headphones, and replaced high-risk sequences with slower, lower-contrast animations. Attendance among neurodiverse families increased by 40% the following year.

This case illustrates how well-intentioned design choices can unintentionally exclude vulnerable children—and how simple, informed adjustments restore accessibility and safety.

Evidence-Based Safety Guidelines for Families & Organizers

Preventing adverse reactions requires proactive, layered strategies—not just avoidance, but thoughtful design and communication. The following checklist synthesizes recommendations from the Epilepsy Foundation, American Academy of Pediatrics, and Sensory Processing Disorder Foundation.

- Check frequency and contrast before purchase: Look for products labeled “flicker-free” or “low-flicker” (IEC TR 61000-3-15 compliant). Avoid lights marketed as “strobe,” “disco,” or “party mode” unless explicitly verified safe for photosensitive users.

- Use ambient lighting as buffer: Never rely solely on flashing lights. Maintain consistent background illumination (e.g., warm-white LED floor lamps) to reduce contrast differentials and provide visual anchoring.

- Limit exposure duration: For children with known sensitivities, restrict direct viewing of strobing displays to ≤90 seconds at a time, with ≥2-minute breaks in a calm environment.

- Provide opt-out options: At events, designate clearly marked “low-stimulus zones” with no flashing lights, reduced sound, and seating away from visual focal points.

- Communicate transparently: Post visible signage (e.g., “This display uses rhythmic lighting at 15–20 Hz. Children with light sensitivity, epilepsy, or sensory differences may wish to view from a distance or use sunglasses.”).

- Empower child agency: Teach older children to recognize early warning signs (e.g., “My eyes feel scratchy,” “The lights look wobbly,” “My tummy feels funny”) and practice a simple exit plan.

Expert Insight: What Pediatric Neurologists Emphasize

Dr. Lena Torres, pediatric neurologist and director of the Childhood Epilepsy & Neurodevelopmental Disorders Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, stresses that prevention begins long before the holidays:

“Many parents don’t realize that photic sensitivity can emerge or intensify during developmental windows—especially between ages 4 and 12. It’s not always present at birth, and it’s not always permanent. But dismissing a child’s reaction as ‘just being dramatic’ delays recognition of treatable conditions and denies them tools for self-advocacy. Lighting isn’t neutral—it’s part of the therapeutic environment. When we design with neurodiversity in mind, we don’t water down the experience—we deepen its humanity.” — Dr. Lena Torres, MD, FAAN

Dr. Torres also cautions against over-reliance on sunglasses as a universal solution: while tinted lenses (particularly FL-41 rose-tinted) can reduce visual stress for some, they do not eliminate seizure risk in photosensitive epilepsy and may even increase disorientation in low-light settings if improperly selected.

Step-by-Step: Creating a Safer Holiday Lighting Plan at Home

Follow this actionable, five-step process to evaluate and adapt your home’s holiday lighting—whether you’re decorating a tree, porch, or indoor space.

- Inventory & Identify: Walk through each light display. Note which strings or devices produce rhythmic flashing (not just steady or slow-blinking). Use your smartphone’s video camera—if the screen shows visible banding or rolling lines, the light is likely flickering at a biologically active frequency.

- Measure Contrast (Quick Method): Hold a white sheet of paper near the light source in a dim room. If the lit area appears intensely bright while surrounding areas remain deep black, contrast is high (>85%). Replace or diffuse such lights with frosted sleeves or sheer fabric overlays.

- Test Tolerance Window: With your child present (and consenting), activate one suspected light for 30 seconds. Observe for subtle cues: blinking rate increase, pupil dilation, head turning away, or verbal discomfort. Stop immediately if any occur—even if no full meltdown follows.

- Modify or Substitute: Replace high-risk lights with alternatives: warm-white steady LEDs, fiber-optic trees (no electrical flicker), or projection-based “light snow” that diffuses intensity. For programmable strips, choose “fade” or “breathing” modes instead of “pulse” or “strobe.”

- Create a Response Protocol: Establish a family phrase (“Lights feel loud—let’s go to the quiet room”) and keep noise-canceling headphones and a soft blanket in your designated calm zone. Practice the protocol once before guests arrive.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can strobe lights cause long-term harm—even without a seizure?

Yes. Repeated exposure to provocative frequencies can contribute to chronic visual fatigue, persistent headaches, sleep disruption (by interfering with melatonin release), and increased baseline anxiety in sensitive children. While not life-threatening in most cases, these effects impair learning, emotional regulation, and daily functioning. Consistent avoidance supports neurological recovery and resilience.

My child loves flashing lights—does that mean they’re not sensitive?

Not necessarily. Some children experience paradoxical attraction: the intense stimulation may temporarily override underlying discomfort, similar to how some individuals with SPD seek spinning or crashing input. Monitor for delayed reactions—irritability, meltdowns, or sleep disturbances occurring hours after exposure. Enthusiasm does not equal safety.

Are battery-operated lights safer than plug-in ones?

Battery operation doesn’t guarantee safety. Many battery-powered string lights use switching circuits that generate high-frequency ripple—often undetectable to the eye but measurable with an oscilloscope. Always verify flicker performance via manufacturer specifications or third-party testing (e.g., IEEE 1789 compliance statements), not power source alone.

Conclusion: Celebrating Light Without Overwhelming the Senses

Holiday lights symbolize warmth, hope, and connection. But true celebration means ensuring every child can experience that light—not just visually, but safely, comfortably, and with dignity. Recognizing strong reactions to strobe-like effects isn’t about eliminating wonder; it’s about expanding our definition of inclusivity to include neurological safety as a foundational right. When we choose lighting that respects developing brains, we teach children that their sensory experiences matter—that their discomfort is valid, their boundaries worthy of honor, and their presence non-negotiable in shared joy. Start this season by auditing one string of lights. Adjust one setting. Post one sign. That small act ripples outward: validating a child’s nervous system, educating a neighbor, modeling compassion for future generations. The most enduring holiday tradition isn’t perfect brightness—it’s thoughtful, responsive, deeply human light.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?