Every year, millions of households plug in strings of Christmas lights—only to discover flickering bulbs, melted wire jackets, or worse: a faint acrid smell, discolored plugs, or tripped breakers. These aren’t random glitches. They’re often the direct result of ignoring one critical specification printed (in tiny font) on the packaging: the maximum number of strands that can be safely connected end-to-end—or, equivalently, the voltage limit per circuit. Unlike household outlets that deliver a steady 120V AC (in North America), Christmas light strands are engineered as *distributed low-voltage systems*, where each bulb, wire gauge, insulation rating, and connector plays a precise role in managing electrical stress. Exceeding voltage limits doesn’t just “make lights dimmer.” It triggers cascading physical failures rooted in Ohm’s Law, thermal physics, and electrical code compliance. Understanding why those limits exist—and what truly occurs when they’re breached—is essential not only for holiday safety but for protecting your home, wiring, and loved ones.

The Physics Behind the Limit: It’s Not Just About Bulbs

Modern mini-light strands (especially LED types) rarely operate at full line voltage across the entire string. Instead, they use one of two primary configurations: series-wired incandescent strings or parallel-wired (or segmented-series) LED strings. In traditional 50-light incandescent sets, all bulbs are wired in series—meaning current flows through each bulb sequentially. A typical set is designed so that 50 bulbs divide the 120V supply evenly: ~2.4V per bulb. If you connect three such strings end-to-end, the total voltage drop becomes 360V—but the outlet still supplies only 120V. So why the warning against daisy-chaining more than three or four strands?

The answer lies in cumulative resistance and voltage drop—not total applied voltage. As current travels down increasingly long runs of thin-gauge wire (often 28–30 AWG), resistance rises. According to P = I²R, even small resistance generates heat. More critically, voltage drop along the wire means the last bulbs in a long chain receive significantly less than their rated voltage. Under-voltage causes incandescents to glow dimly and run cooler—but also shifts filament resistance, altering current draw unpredictably. For LEDs, under-voltage may cause erratic blinking or complete dropout. But the real danger emerges at the *beginning* of the chain: the first few sockets and the male plug carry the *full load current* of every downstream strand. That current multiplies with each added string. A single 50-light incandescent strand draws ~0.33A; five in series demand ~1.65A through the first plug’s contacts and internal wiring—far beyond what its molded plastic housing and 18AWG internal jumpers were tested to handle continuously.

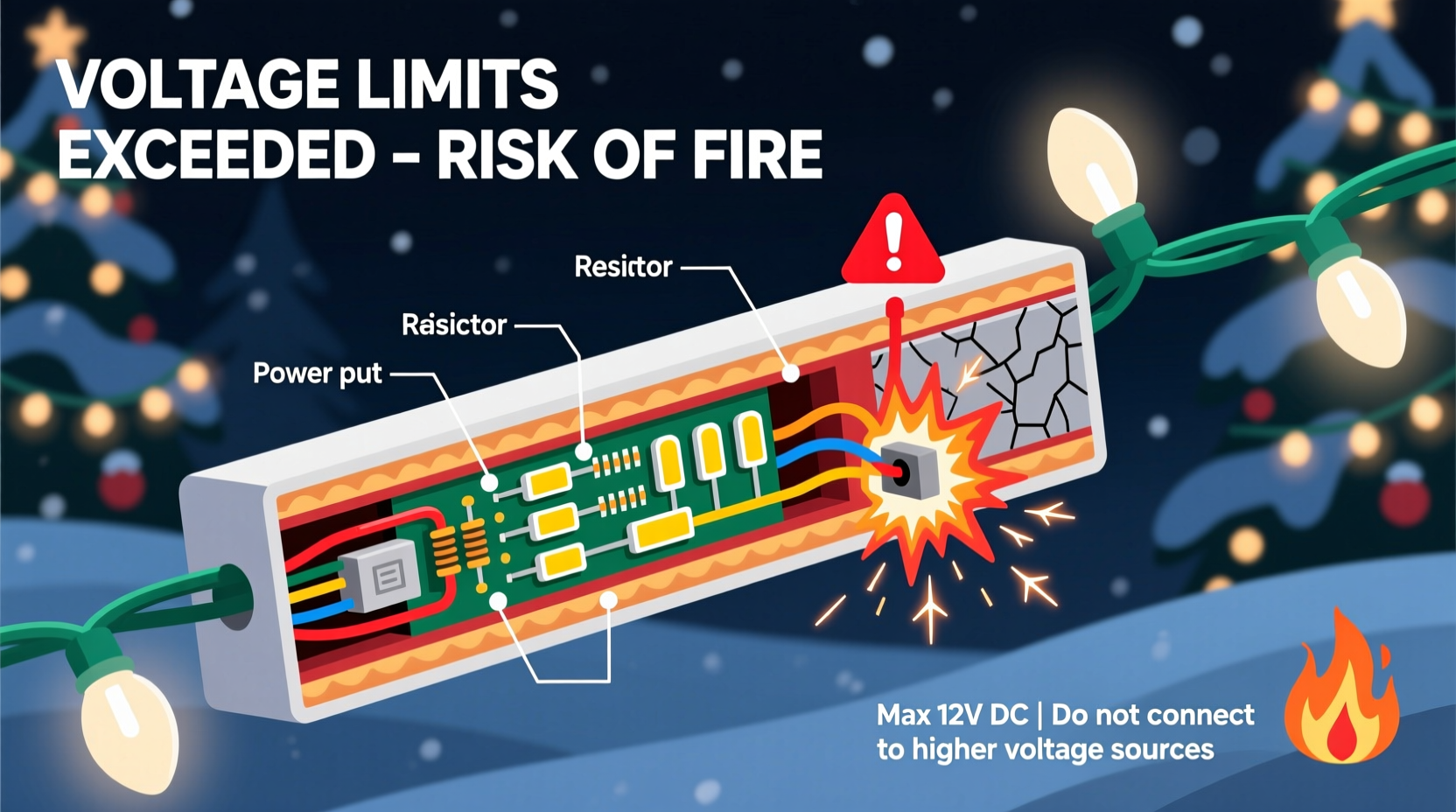

What Actually Happens When You Exceed the Voltage/Current Limit

Exceeding voltage or current limits rarely results in an instantaneous explosion. Instead, failure unfolds in predictable, observable stages—each escalating in risk:

- Stage 1: Thermal Buildup in Connectors & Plugs — The male plug’s brass contacts and internal solder joints begin warming noticeably after 30–60 minutes. Plastic housings soften, discolor (yellowing or browning), and emit a faint “hot plastic” odor. This is the first visible sign of resistive heating exceeding design tolerances.

- Stage 2: Insulation Degradation — Prolonged heat exposure embrittles PVC wire insulation. Micro-cracks form, especially at stress points like cord exits and socket bases. Moisture ingress (even indoor humidity over time) then creates leakage paths, increasing shock risk and enabling arcing.

- Stage 3: Intermittent Arcing & Flickering — As insulation fails or contacts oxidize, tiny arcs occur inside sockets or at plug connections. These produce microsecond bursts of intense heat (~3,000°C), carbonizing nearby plastic and creating conductive carbon tracks—effectively turning insulation into a resistor path. Lights flicker erratically; some sections go dark while others surge brightly before failing.

- Stage 4: Sustained Arcing or Thermal Runaway — Once carbon tracking bridges conductors, current bypasses intended paths. Localized temperatures exceed 600°C—melting copper, igniting insulation, and potentially setting nearby combustibles (curtains, pine boughs, dry wood trim) ablaze. UL tests show that overloaded light cords can ignite adjacent paper in under 90 seconds.

This progression isn’t hypothetical. It’s documented in NFPA fire investigation reports and replicated in UL’s 2580 standard testing for seasonal lighting.

LED vs. Incandescent: Different Limits, Same Risks

Many assume LED lights eliminate these dangers because they draw less power. While true per bulb, the underlying physics of connector stress and thermal management remain identical—and in some cases, more deceptive. LED strands often use “constant-current” drivers or built-in resistors. But cheaply manufactured sets frequently skimp on connector quality and thermal dissipation. A 100-light LED string may draw only 0.07A—yet its $1.99 molded plug may use undersized contacts rated for 0.5A continuous. Chain ten of them, and you’re pushing 0.7A through components certified for half that load.

Worse, LED drivers generate heat internally. When enclosed in tight spaces (e.g., behind garlands or inside wreaths), that heat has nowhere to dissipate. Combined with ambient temperature rise from adjacent strands, driver capacitors degrade faster, leading to premature failure or catastrophic short circuits.

| Feature | Incandescent Strands | LED Strands |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Current per 50-Light Strand | 0.33A | 0.04–0.08A |

| Max Recommended Daisy-Chain (per UL) | 3–5 strands | 10–45 strands (varies widely by model) |

| Primary Failure Mode | Filament burnout → increased current → thermal overload | Driver capacitor failure → intermittent operation → thermal runaway |

| Critical Weak Point | First male plug & socket contacts | Driver housing & input connector |

| Fire Risk Profile | High (glowing filaments + hot wires) | Moderate–High (insidious thermal buildup in sealed drivers) |

A Real-World Case Study: The Suburban Living Room Fire

In December 2022, a family in suburban Ohio decorated their 20-foot Douglas fir with 17 strands of mixed LED and incandescent lights. To avoid running multiple extension cords, they daisy-chained 12 strands—including six vintage incandescent sets labeled “max 3 in series”—into a single heavy-duty outlet strip. The tree stood near a lace curtain and wooden mantel.

At 10:17 p.m., the homeowner noticed a “burnt sugar” smell. By 10:23, smoke was curling from the base of the tree near the third strand’s male plug. Firefighters arrived within four minutes but couldn’t save the living room. The official report cited “excessive daisy-chaining of non-compliant light strings resulting in thermal degradation of plug contacts, sustained arcing, and ignition of adjacent combustible materials.” Notably, the outlet strip’s breaker did *not* trip—the fault current remained below its 15A threshold, but well above the plug’s 5A thermal rating. This underscores a critical reality: circuit breakers protect wiring, not connectors. They won’t prevent a plug from melting.

Expert Insight: What Electrical Engineers and Fire Marshals Emphasize

“The ‘voltage limit’ printed on light packaging is really a *thermal safety limit*. It represents the longest length of wire and highest current load the manufacturer validated to stay below 60°C surface temperature under worst-case ambient conditions (25°C room, no airflow). Exceed it, and you’re not just risking lights—you’re installing a slow-cook heater in your home.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Senior Electrical Safety Engineer, UL Solutions

“We see an average of 180 home fires annually linked to decorative lighting. Over 70% involve improper connection practices—especially daisy-chaining beyond manufacturer limits or using damaged/aged cords. It’s the most preventable cause of holiday fires we investigate.” — Chief Michael Renner, U.S. Fire Administration National Fire Data Center

Practical Safety Checklist: Before You Plug In This Year

- ✅ Read the fine print on the first plug—not the box—and obey the “max connectable” number strictly.

- ✅ Inspect every strand before use: discard any with cracked sockets, exposed wire, bent pins, or discolored plugs.

- ✅ Use outdoor-rated cords indoors only if necessary—and never overload a single outlet or power strip (max 80% of its rated load).

- ✅ Unplug lights when sleeping or leaving home—no exceptions. Timers help, but manual verification is safer.

- ✅ Keep lights away from high-traffic areas where cords get stepped on or pinched—mechanical damage compromises insulation instantly.

- ✅ Replace pre-2010 incandescent strands: older sets lack modern thermal fuses and use thinner, less flame-retardant wire.

FAQ: Clearing Common Misconceptions

“My lights work fine after connecting eight strands—so the limit must be overly cautious, right?”

No. Functionality ≠ safety. Many overloaded setups operate for hours or even days before thermal degradation reaches critical failure. UL testing requires sustained operation at elevated temperatures for 168 hours (7 days) to validate safety margins. What feels “fine” now may be degrading internal components silently.

“Can I use a higher-rated extension cord to safely chain more lights?”

No. Extension cord rating applies to the cord itself—not the connectors on your light strands. The weak point remains the light string’s molded plug and internal wiring, which cannot be upgraded. A 12AWG cord won’t prevent a 28AWG internal jumper from overheating.

“Do battery-operated lights have voltage limits too?”

Yes—though different. Battery sets have maximum recommended run times to prevent cell overheating or leakage. Lithium-based strings (common in premium decor) carry specific warnings against continuous operation beyond 8–12 hours due to thermal management constraints in compact housings.

Conclusion: Respect the Spec, Protect What Matters Most

Voltage limits on Christmas light strands aren’t arbitrary marketing constraints or outdated relics of incandescent technology. They are rigorously tested thresholds—rooted in material science, thermodynamics, and decades of fire incident analysis—that define the boundary between festive illumination and preventable hazard. Every time you ignore that “max 3 strands” label, you’re asking copper, plastic, and physics to perform outside their certified safety envelope. The consequences aren’t theoretical: they’re measured in charred drywall, smoke-damaged heirlooms, and emergency responders responding to avoidable blazes on Christmas Eve. This season, let intention replace habit. Take thirty seconds to count your strands. Swap out that frayed cord. Unplug before bed—not as a suggestion, but as non-negotiable protocol. Your home’s integrity, your family’s safety, and the quiet joy of lights glowing without anxiety depend on it. Don’t wait for a warning smell or a tripped breaker. Start tonight: audit one string, verify its limit, and commit to honoring it—every single year.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?