Every holiday season, millions of households encounter the same frustrating phenomenon: a string of Christmas lights glows brightly—until one section goes dark while the rest remains lit. Or worse: half the strand dies, then a third, then another segment—leaving you staring at a patchwork of illumination and shadow. This isn’t random failure. It’s the unmistakable signature of a series-wired light string—and understanding why it behaves this way is the first step toward reliable, long-lasting holiday lighting. Unlike household wiring or modern LED parallel designs, traditional incandescent mini-light strings rely on series circuit architecture—a clever, cost-effective engineering choice that carries inherent trade-offs. When one bulb fails, the entire circuit path breaks. But why does that often manifest as *sections* going dark—not the whole string? And why do some sections stay lit while others flicker or dim? The answers lie in voltage distribution, fault tolerance design, and subtle manufacturing decisions most consumers never see.

How Series Circuits Work—and Why They’re Used in Christmas Lights

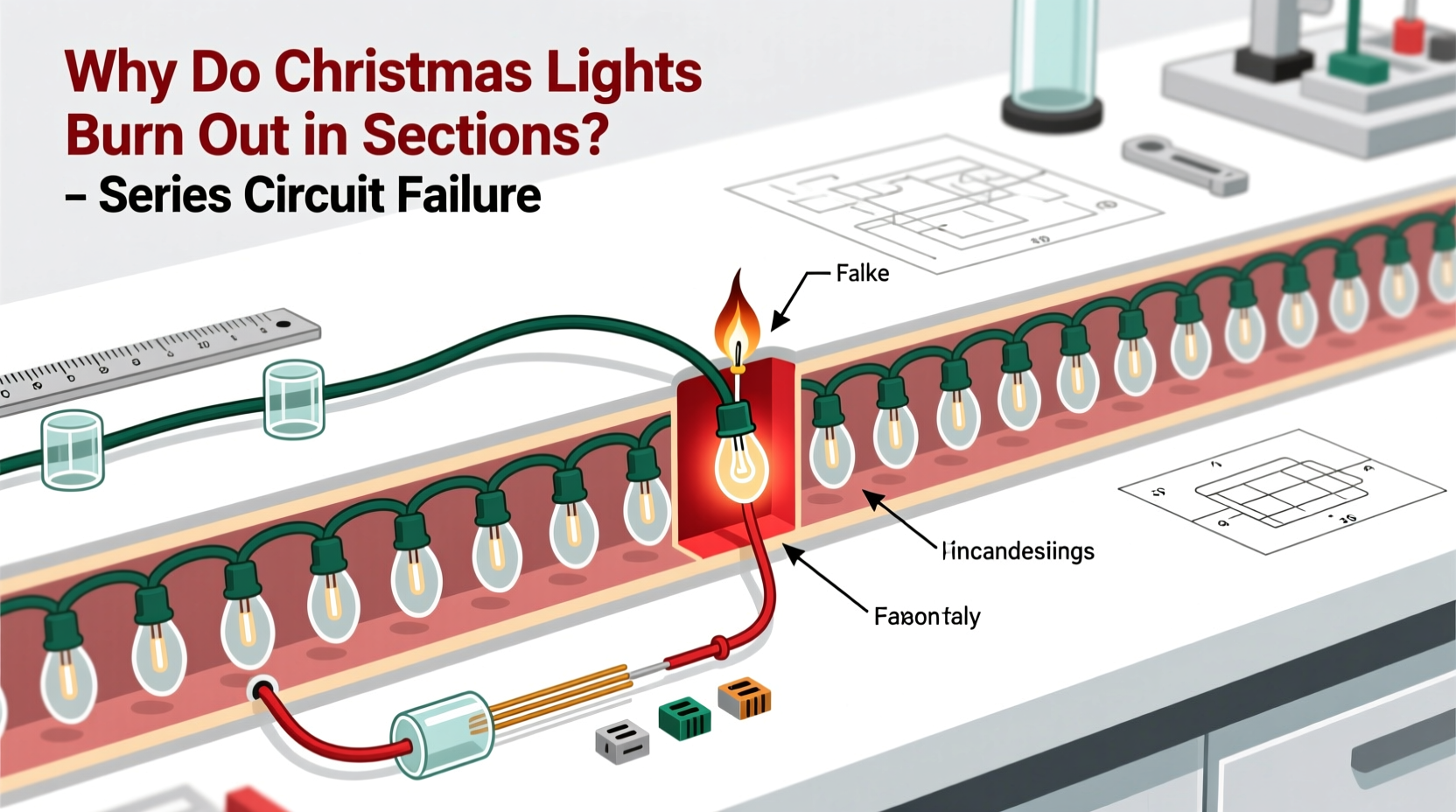

Christmas light strings—especially older incandescent models—are wired in series: electricity flows from the plug, through each bulb’s filament in sequence, and back to the source. There are no independent branches. For current to flow and bulbs to illuminate, every single bulb must complete the circuit. If any bulb’s filament breaks (a “burnout”), the circuit opens and current stops flowing entirely. So why don’t *all* bulbs go dark at once?

The answer is segmentation. Most standard 100-light incandescent strings are not one continuous series loop. Instead, they’re divided into 5–10 smaller series sub-circuits—typically 20 bulbs per section—wired in parallel *to each other*, but with each section internally wired in series. This hybrid design balances cost, safety, and usability. A full-string series circuit would require high voltage (e.g., 120V ÷ 100 bulbs = 1.2V per bulb), making individual bulbs fragile and difficult to manufacture reliably. By grouping bulbs into lower-voltage sections (e.g., 20 bulbs × 6V = 120V), manufacturers produce robust, standardized 6V bulbs that tolerate minor voltage spikes and thermal stress better than ultra-low-voltage alternatives.

This segmentation explains the “sectional” failure pattern: when one bulb burns out in a 20-bulb series section, only *that section* loses continuity—and goes dark—while parallel-connected sections remain unaffected. It’s a deliberate compromise: localized failure instead of total outage.

The Real Culprit: Shunt Wires and Why They Fail

So if a broken filament should kill an entire series section, why do some strings keep working—even after a bulb burns out? The answer is the shunt—a tiny, coiled wire inside the bulb’s base designed to bypass a failed filament. When the filament breaks, the resulting voltage surge across the open gap causes the shunt’s insulation to vaporize, completing the circuit again. This “self-healing” feature lets the rest of the section stay lit—until the shunt itself degrades or fails.

But shunts aren’t foolproof. Over time, repeated surges, moisture ingress, corrosion at the socket contacts, or poor-quality shunt metallurgy cause them to malfunction. When a shunt fails *open* (doesn’t activate), the section goes dark. When it fails *shorted* (stays conductive even when intact), it can overvolt neighboring bulbs, accelerating their burnout. Worse, many budget strings use shunts rated for only 1–2 activations—meaning after two or three burnouts in the same section, the shunt may permanently open, killing the entire segment.

Diagnosing Sectional Failure: A Step-by-Step Troubleshooting Guide

Before replacing the entire string, methodically isolate the fault. This saves time, money, and seasonal frustration.

- Unplug the string and inspect for obvious damage: cracked bulbs, bent pins, melted sockets, or frayed cord near the plug or end connector.

- Identify the dead section: Note exactly which consecutive bulbs are dark. Count how many bulbs are in the section (usually 20 or 25). Confirm adjacent sections are fully lit—this verifies the issue is isolated, not a power supply problem.

- Check the first and last bulb in the dead section. These are common failure points due to higher mechanical stress and voltage exposure. Gently wiggle each bulb—if the section briefly lights, the socket contact is loose or corroded.

- Use a bulb tester or multimeter: Set to continuity or low-voltage DC. Touch probes to the metal screw shell and bottom contact of each bulb. A good bulb reads ~6–12Ω (incandescent) or shows continuity (LED with shunt). No continuity = dead bulb *or* failed shunt.

- Test shunt functionality: With power off, insert a known-good bulb into the first socket of the dead section. If the section lights, the original bulb’s shunt failed open. If it remains dark, test the next socket—repeat until you find the faulty bulb or discover a broken wire between sockets.

- Inspect internal wiring: If all bulbs test good, carefully examine the wire between sockets in the dead section. Look for nicks, kinks, or discoloration indicating a break or high-resistance joint.

Do’s and Don’ts of Series Light Maintenance

| Action | Do | Don’t |

|---|---|---|

| Bulb Replacement | Use identical voltage/wattage bulbs (e.g., 2.5V/0.3A). Match base type (E10 candelabra). | Substitute with higher-voltage bulbs—even if they fit physically. This underpowers neighbors and stresses shunts. |

| Storage | Wrap loosely around a cardboard tube; store in cool, dry, dark place. Avoid compression. | Wind tightly on spools or shove into plastic bins—causes wire fatigue and socket deformation. |

| Cleaning | Wipe sockets with isopropyl alcohol on cotton swab to remove oxidation and dust. | Use water, vinegar, or abrasive cleaners—they corrode brass contacts and degrade shunt insulation. |

| Testing | Test strings before decorating. Replace suspect bulbs preemptively. | Plug in damaged strings or use extension cords rated below 10A—overheating risks fire. |

| Upgrading | Add a UL-listed inline fuse adapter (3A slow-blow) to protect against cascade failures. | Connect more than three standard strings end-to-end—exceeds safe amperage and overheats first-section wiring. |

Real-World Example: The Johnson Family’s December Dilemma

The Johnsons hung their 25-year-old heirloom C7 incandescent garland along the porch railing. On December 10, the middle third—30 bulbs—went dark. Their first instinct was replacement. But their 12-year-old son, who’d taken an electronics elective, suggested troubleshooting. Using a $5 bulb tester, he found two bulbs with open filaments—but replacing them didn’t restore light. He then checked continuity across each socket and discovered a hairline crack in the insulated wire between bulbs #14 and #15 in the section. The crack had oxidized over decades of outdoor exposure, creating high resistance—enough to drop voltage below the threshold needed to light the remaining bulbs, even though the circuit wasn’t fully open. A soldered repair and dielectric grease on the joint restored full function. The family kept the lights for three more seasons—proving that understanding series behavior transforms perceived obsolescence into repairable infrastructure.

Expert Insight: Engineering Trade-Offs Behind the Glow

“The series-with-shunt design was never about elegance—it was about economics and reliability at scale. In the 1960s, producing 100 million identical 6V bulbs was vastly cheaper than engineering 120V micro-LEDs. Today’s ‘smart’ strings use constant-current drivers and parallel topology, but legacy series strings still dominate the value market because they work—when maintained correctly.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Electrical Historian & Senior Engineer, Illuminating Engineering Society (IES)

FAQ: Your Top Series-Circuit Lighting Questions Answered

Can I convert a series string to parallel wiring?

No—without redesigning the entire string’s voltage regulation, doing so would instantly destroy every bulb. Series strings deliver full line voltage (120V) across the *entire section*. Rewiring bulbs in parallel would subject each to 120V instead of its rated 6V, causing immediate catastrophic failure. Conversion requires professional-grade driver modules, rewiring, and safety certification—making replacement more economical.

Why do newer LED strings rarely fail in sections?

Most modern LED strings use constant-voltage parallel architecture with built-in current-limiting resistors or ICs per bulb—or even digital addressable LEDs (like WS2812B) where each LED has its own driver. This eliminates dependency on shunts and filament integrity. However, some budget LED strings *do* mimic series wiring using “dumb” LEDs with integrated shunts—so always check packaging for “parallel wired” or “individually protected” claims.

Is it safe to leave a partially dead string plugged in?

Yes—if only one section is dark and the rest operate normally at stable brightness. However, if adjacent sections dim, flicker, or buzz, unplug immediately: this indicates overcurrent stress, failing insulation, or a short developing in the wiring harness. Persistent sectional failure across multiple seasons signals degraded shunts or socket corrosion—replace the string before fire risk increases.

Preventing Sectional Burnouts: Proactive Strategies That Last

Prevention begins before the first bulb glows. Start with selection: choose strings labeled “UL Listed,” “shunt-protected,” and “heavy-duty” (18-gauge wire vs. standard 22-gauge). Thicker wire reduces resistance heating and voltage drop across long runs. Next, implement seasonal habits: always unplug before adjusting bulbs; avoid hanging lights where they’ll sway against rough surfaces (causing socket abrasion); and never staple wires directly to wood or brick—use insulated clips to prevent insulation cuts.

For outdoor use, add a GFCI-protected outlet and inspect sockets annually for white powdery corrosion (aluminum oxide) or green patina (copper sulfate). Clean with electrical contact cleaner—not WD-40, which leaves residue that attracts dust and conducts poorly. Finally, retire strings showing three or more sectional failures in one season. Fatigue in the copper bus wire and cumulative shunt degradation make further reliability unlikely.

Conclusion: Master the Circuit, Not Just the Lights

Christmas lights burning out in sections isn’t a flaw—it’s physics made visible. It’s the quiet language of series circuits speaking through glowing filaments and silent shunts. When you understand why a single burnt bulb can silence twenty others—or why a corroded socket mimics a dead filament—you shift from passive consumer to informed steward. You stop seeing strings as disposable holiday props and start recognizing them as engineered systems worthy of thoughtful maintenance. That knowledge pays dividends: fewer last-minute trips to the hardware store, safer displays, longer-lasting investments, and the quiet satisfaction of solving a problem that’s baffled generations of decorators. This holiday season, don’t just hang lights—understand them. Test one string before decorating. Replace two suspect bulbs—not just the dark ones. Share your troubleshooting wins with a neighbor. Because the warmest glow isn’t just from the bulbs—it’s from knowing exactly why they shine, and how to keep them shining longer.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?