Every holiday season, millions of households string lights across eaves, wrap trees, and drape garlands—often relying on extension cords to bridge the gap between outlet and display. It’s common to notice that cord growing noticeably warm to the touch after an hour or two. That warmth isn’t inherently alarming—but it’s also not something to ignore. Understanding why it happens, how much heat is acceptable, and what signals real danger separates thoughtful seasonal decorating from preventable risk. This isn’t about fear-mongering; it’s about recognizing the quiet physics at play and responding with informed judgment.

The Physics Behind the Warmth: Resistance, Current, and Power Loss

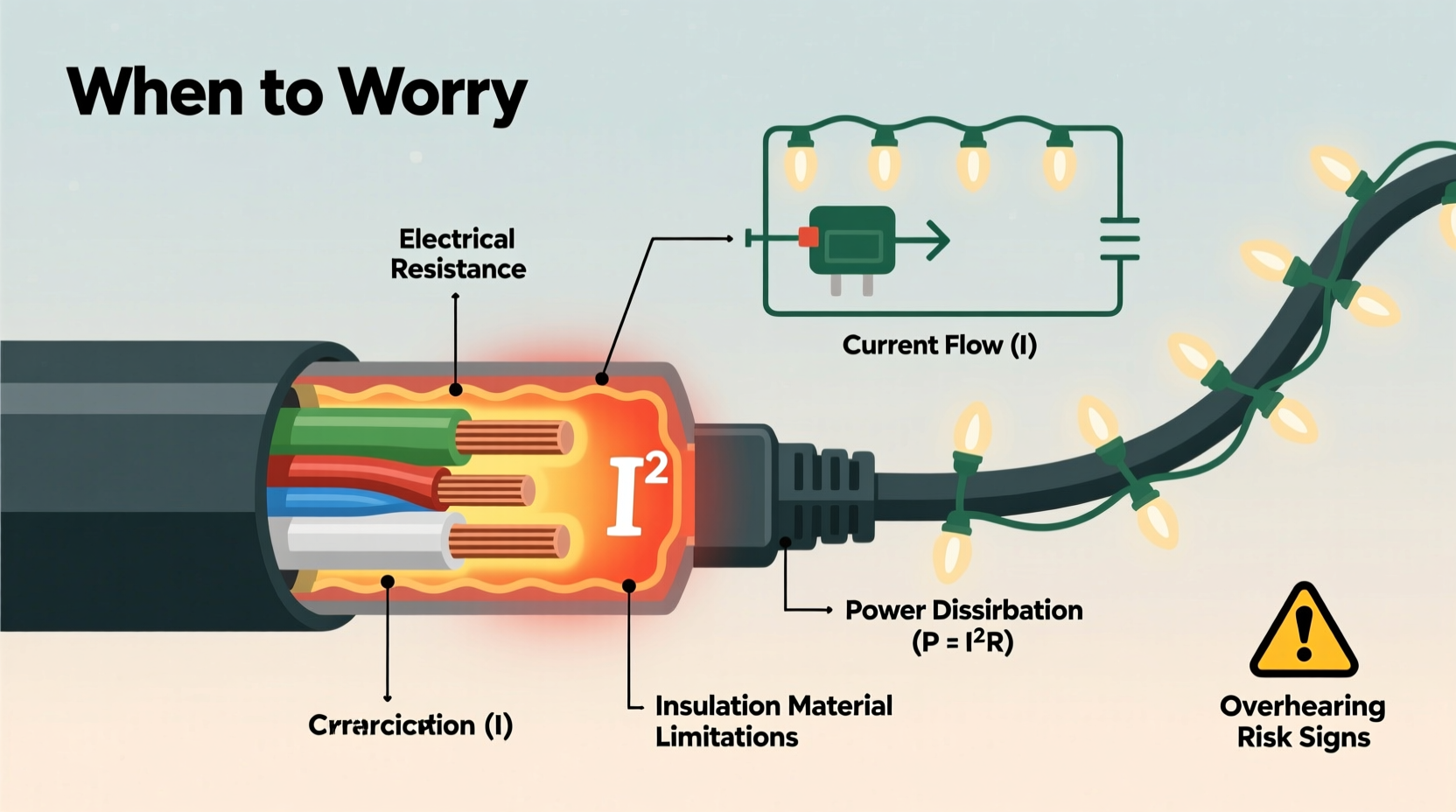

When electricity flows through a conductor—like the copper wire inside an extension cord—it encounters resistance. That resistance isn’t a flaw; it’s an inherent property of all materials (except superconductors, which require extreme cold). As electrons move, they collide with atoms in the wire lattice, converting some electrical energy into thermal energy. This is known as Joule heating, governed by the formula: P = I² × R, where P is power lost as heat (in watts), I is current (in amperes), and R is the cord’s resistance (in ohms).

Crucially, heat generation scales with the square of the current. Double the current, and heat quadruples. A single string of 100 LED mini-lights draws only about 0.04 amps. But connect ten such strings in series—or worse, daisy-chain multiple cords—across a single 16-gauge, 50-foot cord rated for just 10 amps, and current can climb to 3–5 amps. At that load, resistance (even low) adds up—and so does heat.

Wire gauge matters profoundly. A 16-gauge cord has higher resistance per foot than a 14-gauge cord, which in turn has more resistance than a 12-gauge cord. Longer cords compound resistance further. So a 100-foot, 16-gauge cord powering 200 feet of incandescent C9 lights (drawing ~7.5 amps) may reach 110°F (43°C) at its midpoint—not hot enough to ignite insulation, but well above ambient and a clear signal of strain.

When Warmth Is Normal—and When It Crosses Into Danger

A slight, barely perceptible warmth—especially near the plug end or along the first few feet—is typical under moderate, sustained load. That’s because resistance is highest where connections occur (plug-to-cord, cord-to-receptacle), and heat dissipates less efficiently there. What’s critical is distinguishing between benign warmth and hazardous heat.

Here’s how to assess:

- Comfort test: If you can hold your palm flat against the cord for 5 seconds without pulling away, surface temperature is likely below 113°F (45°C)—generally safe for modern thermoplastic insulation.

- Hot-spot test: Localized heat—especially at splices, damaged sections, or where the cord bends sharply—indicates high resistance at that point. That’s never normal.

- Odor or discoloration: A faint “hot plastic” smell, yellowing, cracking, or stiffness in the jacket signals insulation breakdown. Stop use immediately.

- Outlet or plug warmth: If the wall outlet, power strip, or cord plug itself feels hot, the problem is likely upstream—overloaded circuit, loose connection, or failing receptacle.

“Temperature rise in extension cords is expected—but it must remain within engineered limits. UL standards require cords rated for 105°C internal conductor temperature to limit external surface temperatures to no more than 60°C (140°F) under full-rated load. Anything consistently above 120°F (49°C) warrants immediate investigation.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Electrical Safety Engineer, Underwriters Laboratories (UL)

Real-World Scenario: The Overlooked Porch Display

In December 2022, a homeowner in Portland, Oregon, installed 12 strands of vintage incandescent icicle lights on her front porch—totaling 1,440 bulbs. She used a single 100-foot, 16-gauge extension cord purchased in 2015, running from an indoor GFCI outlet through a cracked exterior door jamb. For three days, the cord felt “a little warm.” On the fourth evening, her teenage son noticed the cord’s outer jacket had softened and warped near the doorframe, emitting a faint acrid odor. He unplugged it. Inspection revealed the cord had been pinched and abraded by the door, exposing inner conductors. The localized resistance had raised that section’s temperature to an estimated 185°F (85°C)—well beyond safe limits, with melted insulation and carbon tracking visible under magnification.

No fire occurred—but the near-miss underscores two critical points: degradation compounds risk, and warmth that escalates over time is never “just part of the season.” Had she checked the cord’s rating (16 AWG = max 10A), calculated the load (1,440 incandescent bulbs ≈ 12 amps), and inspected for physical damage, the hazard would have been caught before heat became dangerous.

Safety Thresholds & Practical Load Management

Safe operation hinges on matching cord capacity to actual load—and understanding how ratings translate to real-world use. Below is a concise reference table comparing common cord types, their ampacity, and realistic Christmas light capacity.

| AWG Gauge | Max Continuous Amps (Indoor/Outdoor) | Typical Length Rating | LED Light Capacity (100/bundle) | Incandescent Light Capacity (100/bundle) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 AWG | 5 A | Up to 25 ft | ~125 strings | ~12 strings |

| 16 AWG | 10 A | Up to 50 ft | ~250 strings | ~25 strings |

| 14 AWG | 15 A | Up to 100 ft | ~375 strings | ~37 strings |

| 12 AWG | 20 A | Up to 150 ft | ~500 strings | ~50 strings |

Note: These capacities assume ideal conditions—room temperature, no coiling, no direct sun exposure, and undamaged insulation. Real-world derating applies: reduce capacity by 20% for outdoor use in cold weather (stiffer insulation increases resistance), and by 30% if the cord is tightly coiled or bundled under mulch or snow.

To calculate your actual load: find the wattage label on each light set (e.g., “48W”), sum total watts, then divide by voltage (120V in North America). Example: 8 sets × 48W = 384W ÷ 120V = 3.2A. That fits easily on a 16-gauge cord—but add a 150W animated reindeer, a 60W inflatable snowman, and a 200W spotlight, and you’re at 6.4A—still safe, but approaching 64% of capacity. That’s where vigilance begins.

Actionable Safety Checklist: Before You Plug In

Follow this verified checklist every year—before hanging a single bulb—to ensure cord safety:

- Inspect visually: Look for cuts, abrasions, exposed wires, cracked or brittle jacket, bent or discolored plugs.

- Check rating labels: Confirm AWG gauge, amperage rating, and “UL Listed” or “ETL Verified” mark. Discard any cord without legible rating or with faded markings.

- Verify length vs. load: Use the shortest cord possible. Avoid extension cords longer than necessary—even if rated, longer length increases resistance and voltage drop.

- Never daisy-chain: Connecting multiple extension cords multiplies resistance and heat. Use one appropriately sized cord instead.

- Elevate and separate: Keep cords off wet ground, away from foot traffic, and uncoiled. Never run under rugs or furniture where heat can’t dissipate.

- Use outdoor-rated cords only outside: Indoor cords lack UV-resistant jackets and moisture sealing—degrading faster and becoming unsafe in rain or snow.

- Test GFCI protection: Plug into a GFCI outlet or use a GFCI-protected power strip. Press “TEST” and “RESET” to confirm functionality.

Step-by-Step: How to Diagnose and Respond to Unexpected Heat

If you notice unusual warmth while lights are operating, follow this sequence—calmly and deliberately:

- Unplug immediately—do not yank the cord; grasp the plug body and pull straight out.

- Let it cool completely (at least 30 minutes) before handling.

- Examine the entire cord path: Check for kinks, compression points, proximity to heat sources (vents, heaters), and contact with flammable materials (dry pine boughs, paper decorations).

- Measure actual load: Use a plug-in power meter (under $25) to confirm real-time wattage and amperage. Compare to the cord’s rated capacity.

- Check connections: Ensure plugs are fully seated, outlets aren’t loose, and no adapters or multi-plug strips are overloaded.

- Decide: If inspection reveals damage, discoloration, or mismatched load/capacity, retire the cord. If everything appears intact and load is within spec, retest for 15 minutes—monitoring closely. If warmth recurs rapidly, replace the cord regardless.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I use a heavy-duty extension cord for all my lights—even if it feels cool?

Not necessarily. “Heavy-duty” refers to jacket thickness and durability—not automatic suitability. A 12-gauge cord rated for 20A is overkill for 50 feet of LED lights drawing 1.5A, but it’s essential for powering a large inflatable display plus lights totaling 15A. Always match gauge and length to calculated load—not just perceived robustness.

Why do some cords warm up more near the plug than along the middle?

Heat concentrates at points of highest resistance: the plug’s internal contacts, crimped connections, and the transition where wire meets blade. Poor manufacturing, corrosion, or repeated plugging/unplugging can increase resistance there. If only the plug is warm while the cord stays cool, inspect the plug for bent blades, scorch marks, or looseness.

Is it safe to wrap warm cords in aluminum foil to “cool them down”?

No—this is extremely dangerous. Foil traps heat, insulates the cord further, and may cause short circuits if it contacts exposed metal. It also violates NEC (National Electrical Code) requirements for free air circulation around conductors. If a cord needs cooling, it’s already overloaded or defective. Unplug and replace it.

Conclusion: Warmth Is Information—Not Background Noise

That gentle warmth under your palm isn’t just physics at work—it’s feedback. It’s the cord telling you about current flow, resistance, age, and environment. Dismissing it as “just Christmas” ignores decades of electrical safety science—and risks turning tradition into tragedy. Modern LED lights have slashed energy demand, but they haven’t eliminated risk: older cords, improper setups, and accumulated wear still create hazards. Your vigilance—checking ratings, calculating loads, inspecting annually, and acting decisively on warmth—is the most effective safeguard you own.

This holiday, don’t just decorate. Diagnose. Measure. Replace what’s worn. Choose the right gauge for the distance and load. And when in doubt, unplug—not to spoil the sparkle, but to preserve what matters most: your home, your memories, and everyone gathered beneath those lights.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?