Every holiday season, thousands of households experience the unsettling sensation of a warm—or even hot—extension cord snaking across their porch, driveway, or living room floor. That warmth isn’t just inconvenient; it’s a visible symptom of underlying electrical stress that, if ignored, can escalate into melted insulation, tripped breakers, or worse: an electrical fire. Unlike everyday appliances, holiday lighting setups often combine dozens of strands, varying bulb types (incandescent vs. LED), mixed cord gauges, and outdoor-to-indoor transitions—all while drawing power through a single, sometimes undersized, extension cord. Understanding *why* this heating occurs is not merely academic—it’s a critical safety literacy skill for every homeowner, renter, and seasonal decorator.

The Physics Behind the Warmth: Resistance and Power Dissipation

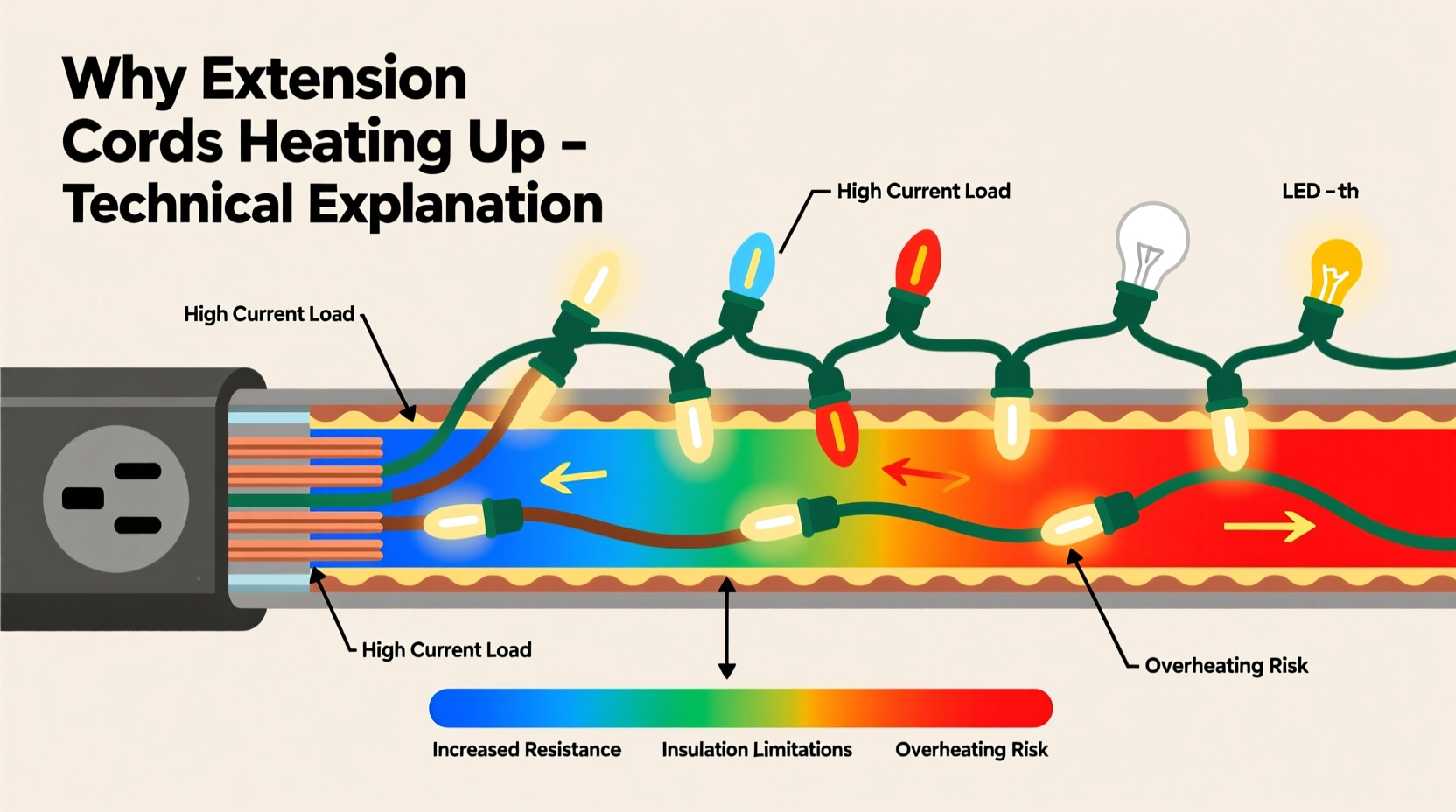

At its core, extension cord heating is governed by Joule’s Law: heat generated in a conductor equals the square of the current (I²) multiplied by its resistance (R) and time (t). In practical terms: H = I² × R × t. Every wire resists the flow of electricity to some degree—and that resistance converts electrical energy into thermal energy. The amount of resistance depends on three physical properties: the wire’s material (copper is low-resistance; aluminum or cheap alloys are higher), its length (longer = more resistance), and its cross-sectional area—commonly referred to as “gauge.”

A 16-gauge cord (common in light-duty indoor extensions) has roughly twice the resistance per foot of a 14-gauge cord—and over three times that of a robust 12-gauge outdoor-rated cord. When you plug ten 50-light incandescent strands (each drawing ~0.33 amps) into a single 16-gauge, 100-foot cord, the total load approaches 3.3 amps—but because resistance compounds over distance, voltage drop occurs, forcing the cord to dissipate excess energy as heat along its entire length. That’s why the middle section of a long cord often feels warmer than the ends: it’s where cumulative resistance peaks.

Overloading: The Most Common—and Preventable—Cause

Most consumers don’t realize that “rated” cord capacity assumes ideal conditions: short runs, ambient temperatures under 86°F (30°C), and no coiling. Yet holiday setups routinely violate all three. A standard 16-gauge extension cord is typically rated for 13 amps *at 10 feet*. At 50 feet, that rating drops to approximately 10 amps. At 100 feet—common for wrapping trees or lining driveways—the safe continuous load may fall to just 7–8 amps.

Here’s where mismatched expectations create danger:

- A single strand of 100 incandescent mini-lights draws ~0.33 amps; 10 strands = 3.3 amps.

- But add two 20-light C9 bulb strings (each ~1.5 amps), a pre-lit wreath (0.5 amps), and an inflatable snowman (1.2 amps), and total draw jumps to ~6.5 amps—well within theoretical limits… until you account for cold-weather brittleness, connector corrosion, and bundled cord storage.

- Now consider LED alternatives: a comparable LED string of 200 lights draws only ~0.04 amps. Ten such strands equal just 0.4 amps—less than a single incandescent strand.

The takeaway? It’s rarely the number of lights alone that overheats a cord—it’s the *type* of lights, *how they’re wired together*, and whether the cord’s real-world ampacity matches the actual load.

Connection Points: Where Heat Concentrates—and Fails

If resistance is the engine of heating, then poor connections are the accelerant. Over 68% of cord-related electrical fires originate at connection points—not along the wire itself—according to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). Why?

Each time two conductors join—whether via a female socket, male plug, or inline tap—the contact surface area shrinks. Even microscopic oxidation, dust, or bent prongs increases localized resistance dramatically. A slightly corroded outlet receptacle can elevate resistance by 500% compared to a clean, tight connection. That tiny hotspot then radiates heat into surrounding plastic housing, softening insulation and inviting arcing.

This effect multiplies in daisy-chained setups. Plugging Cord A into Cord B, then Cord B into Cord C, introduces *three* additional high-resistance interfaces—all before a single light turns on. Add moisture (from rain, snowmelt, or condensation), and electrolytic corrosion begins accelerating within hours.

“An extension cord operating at 120°F (49°C) is already running near its thermal limit. At 140°F (60°C), its insulation begins degrading rapidly—and at 160°F (71°C), many common PVC jackets lose structural integrity. That’s not ‘warm’—that’s pre-failure.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Electrical Safety Engineer, National Fire Protection Association (NFPA)

Real-World Scenario: The Overlooked Porch Setup

In December 2022, a suburban homeowner in Ohio strung 14 strands of vintage incandescent lights across his front porch, garage eaves, and tree. He used a single 100-foot, 16-gauge “indoor/outdoor” cord purchased from a discount retailer. By dusk on opening night, family members noticed the cord felt “uncomfortably warm” near the GFCI outlet. By midnight, the outer jacket had softened and warped around the male plug. The next morning, the plug was fused to the outlet, and the first 12 inches of cord showed visible charring beneath discolored insulation.

Investigation revealed three compounding factors: First, the cord was coiled tightly (in a 24-inch diameter loop) behind the potted plants—trapping heat with zero airflow. Second, the GFCI outlet itself had minor corrosion from prior seasonal use, raising contact resistance by an estimated 320%. Third, two of the light strands had damaged sockets where internal wires were partially exposed, creating intermittent micro-arcs that pulsed additional current surges. The total measured load was 7.2 amps—within the cord’s *nominal* rating but far exceeding its *derated capacity* for length, temperature, and connection quality.

This wasn’t negligence—it was a cascade of understandable oversights. And it’s entirely avoidable with informed habits.

Practical Prevention: A Step-by-Step Safety Protocol

Preventing hazardous heating isn’t about eliminating holiday lights—it’s about engineering resilience into your setup. Follow this field-tested sequence before plugging in:

- Calculate total wattage and convert to amps: Add the wattage listed on each light package (e.g., 20.4W per 50-light incandescent strand). Divide total watts by 120V to get amps. Example: 245W ÷ 120V = 2.04A.

- Select cord gauge based on length and load: For loads over 5A or runs longer than 25 feet, use 14-gauge minimum. For 7–10A or 50+ feet, use 12-gauge. Never use 16- or 18-gauge outdoors or for permanent installations.

- Inspect every connection: Check plugs for bent prongs, scorch marks, or cracked housings. Clean metal contacts with isopropyl alcohol and a soft cloth. Discard any cord with stiffness, cracking, or exposed wire.

- Uncoil completely during use: Never operate a cord while wrapped, bundled, or covered by mulch, rugs, or snow. Allow at least 2 inches of clearance around all plugs and junctions for airflow.

- Use GFCI protection—and test it monthly: Plug into a GFCI outlet or use a GFCI-protected extension cord. Press the “TEST” button before each use; reset with “RESET.” If it won’t reset or trips repeatedly, stop using the circuit immediately.

Do’s and Don’ts: A Holiday Lighting Safety Table

| Action | Do | Don’t |

|---|---|---|

| Cord Selection | Choose 12- or 14-gauge cords labeled “UL Listed for Outdoor Use” and “Heavy-Duty.” Look for SJTW or SJOOW designation. | Use indoor-only cords (SJ, SJE) outdoors—even if “water-resistant.” Never substitute lamp cord (SPT-1/2) for extension duty. |

| Daisy-Chaining | Use a single cord long enough for your run. If unavoidable, limit to one additional cord—and ensure both are same gauge and rated for same amperage. | Chain more than two extension cords. Never plug a power strip into an extension cord unless explicitly rated for it. |

| Light Compatibility | Mix LED and incandescent only if using separate circuits/cords. Prefer LED for >80% of your display—they cut heat, energy, and load by 80–90%. | Assume “all lights are the same.” Incandescent C7 bulbs draw 5× more per bulb than LED equivalents. Verify per-strand specs—not just “50 lights.” |

| Monitoring & Maintenance | Touch-test cords 15 minutes after powering on. If too warm to hold comfortably (>110°F/43°C), unplug and reassess. Re-inspect weekly. | Ignore warmth because “it’s always been like that.” Never leave lights on unattended overnight or while sleeping—especially with older incandescent sets. |

FAQ: Your Top Holiday Electrical Questions—Answered

Can I use an indoor extension cord outside if it’s “waterproof”?

No. Indoor cords (even those with rubbery jackets) lack UV stabilizers and low-temperature flexibility ratings. Exposure to sunlight degrades insulation within weeks; freezing temperatures make them brittle and prone to cracking. Only cords marked “Outdoor,” “W,” or “WR” (Weather Resistant) meet UL 817 standards for exterior use.

Why does my cord heat up more at night than during the day?

Ambient temperature isn’t the main factor—your home’s electrical system is. Many neighborhoods experience higher grid voltage at night (due to reduced industrial demand), pushing more current through fixed-resistance cords. Also, cooler air reduces convective cooling, allowing heat to accumulate faster. This is why nighttime inspections are critical.

Is it safe to wrap lights around an extension cord to hide it?

Never. Wrapping lights—or anything—around a cord restricts heat dissipation and creates friction points that abrade insulation. Instead, use cord covers designed for outdoor use (with ventilation slots) or route cords through conduit. If concealment is essential, bury low-voltage landscape wiring (12V) with proper transformers—not line-voltage extension cords.

Conclusion: Light Up Responsibly—Not Riskily

Holiday lighting should evoke joy, nostalgia, and community—not anxiety or emergency calls. That warm cord isn’t a quirk of the season; it’s physics delivering a clear, urgent message: your electrical infrastructure is under strain. But unlike weather or tradition, this risk is entirely within your control. You don’t need technical expertise—just awareness of cord ratings, respect for connection integrity, and the discipline to measure rather than guess. Switching to LED lights alone can reduce your cord’s thermal load by 85%, extend cord life by years, and slash your electricity bill. Choosing a 12-gauge outdoor cord over a flimsy 16-gauge one costs $12 more—but could prevent $12,000 in fire damage. Inspecting plugs takes 90 seconds—but buys peace of mind for weeks.

This season, let your lights shine brightly—not your cords glow ominously. Audit one setup this weekend: measure its load, inspect its connections, replace one aging cord. Then share what you learned—not just your photos online, but your hard-won safety insight with a neighbor, relative, or new homeowner. Because the most meaningful holiday tradition isn’t just lighting up your home. It’s ensuring everyone returns to it, safely, year after year.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?