Every holiday season, thousands of households string together dozens—or even hundreds—of light strands across porches, trees, and rooftops. Many rely on a single extension cord to power them all. Then, halfway through December, someone notices the cord feels warm. Then hot. Then uncomfortably warm near the plug or midpoint. That warmth isn’t normal. It’s a warning sign: resistance is building, current is exceeding safe limits, and thermal stress is accumulating in insulation and conductors. Left unchecked, that heat can degrade wire insulation, melt connectors, ignite nearby combustibles, or cause arc faults—leading to fires that claim an average of 170 U.S. homes annually during the winter holidays (NFPA, 2023). This guide explains precisely why extension cords overheat when powering multiple light strands—not as theoretical physics, but as practical electrical behavior you can observe, measure, and control. We’ll break down the real-world causes, quantify risk thresholds, and give you actionable, code-aligned steps to protect your home, family, and property.

Why Extension Cords Heat Up: The Physics Behind the Warmth

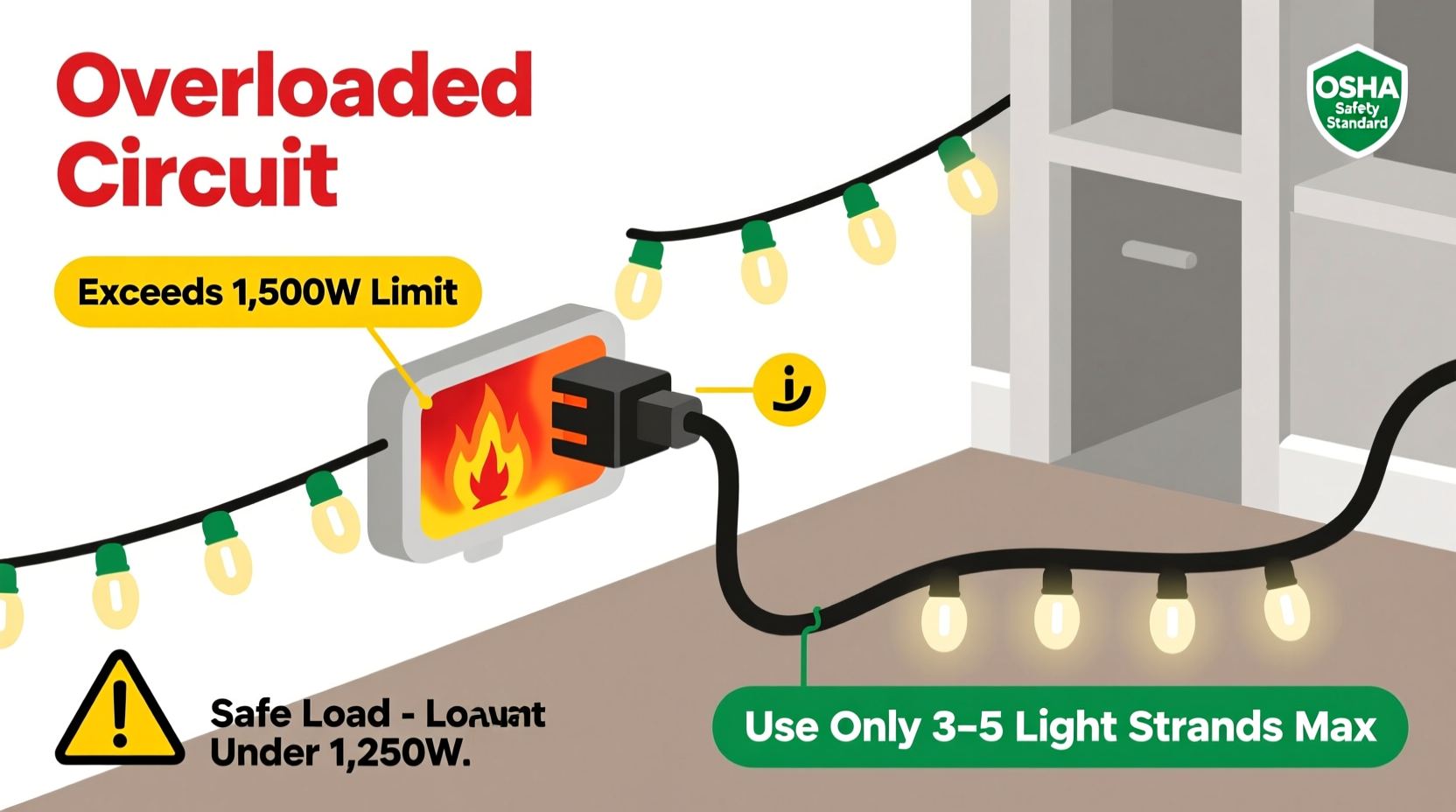

Heat in an extension cord isn’t random—it’s governed by Joule’s Law: P = I² × R, where power dissipated as heat (P) equals the square of current (I) multiplied by resistance (R). In simple terms: double the current, and heat generation quadruples. Light strands draw current—measured in amperes (A)—and each additional strand increases total current flow. But resistance isn’t static. It depends on three fixed variables: conductor material (copper vs. aluminum), wire gauge (thickness), and cord length. Thinner wires (higher AWG numbers like 16 or 18) have more resistance per foot than thicker ones (12 or 14 AWG). Longer cords add cumulative resistance. So when you daisy-chain five 50-light LED strands—each drawing 0.04 A—you’re at 0.2 A: safe for any standard cord. But connect ten 100-light incandescent strands—each pulling 0.33 A—and total load jumps to 3.3 A. Now, if that load runs through a 100-foot, 16 AWG cord (rated for just 5 A max at 100 ft), resistance rises sharply near capacity. Voltage drop follows—often 8–12% at full load—causing lights to dim and the cord to warm noticeably at connection points and midspan. That warmth is energy literally being wasted as heat instead of light. And it escalates rapidly: a cord operating at 90% of its ampacity may feel only slightly warm; at 110%, it can exceed 60°C (140°F)—enough to soften PVC insulation and initiate thermal runaway.

Four Critical Risk Factors You Can’t Ignore

Not all overheating is equal—and not all cords behave the same under identical loads. Four interdependent factors determine whether warmth becomes danger:

- Wire Gauge Mismatch: Most consumer-grade “indoor” extension cords are 16 or 18 AWG—designed for lamps or phone chargers, not sustained lighting loads. A 16 AWG cord is rated for 10 A only up to 50 feet; beyond that, NEC Table 400.5(A)(3) requires derating to 5 A. Yet many users plug 300+ feet of lights into a single 100-ft, 16 AWG cord—unaware they’ve halved its safe capacity.

- Daisy-Chaining (“Cord Stacking”): Connecting one extension cord to another multiplies resistance and introduces two additional failure points: the male plug of Cord A and the female receptacle of Cord B. Each connection adds contact resistance—especially if plugs are worn, corroded, or loosely seated. That tiny resistance (as low as 0.05 Ω) generates disproportionate heat under load: at 5 A, it produces 1.25 W of heat *just at the junction*. Multiply across multiple junctions, and surface temperatures easily surpass 70°C.

- Ambient Temperature & Enclosure: Cords laid under rugs, coiled tightly, or bundled with tape trap heat. NEC Article 400.8(5) explicitly prohibits concealing extension cords in walls, ceilings, or floors—and yet, many run cords along baseboards under curtains or behind furniture. In ambient temps above 30°C (86°F), a cord’s ampacity drops by up to 15%. Combine high ambient heat with poor airflow, and thermal buildup accelerates exponentially.

- Light Type & Load Profile: Incandescent mini-lights draw 5–10× more current than comparable LED strands. A single 100-light incandescent set pulls ~0.33 A; an equivalent LED set pulls ~0.04 A. But many users mix both types on one circuit—or add smart controllers, timers, or fog machines without recalculating total draw. Worse, some “LED” strings use cheap drivers that generate harmonic distortion, increasing RMS current and heating conductors beyond nameplate ratings.

Real-World Case Study: The Garage Outlet Incident

In December 2022, a homeowner in Portland, Oregon, connected six 150-light incandescent strands (total: 900 lights) to a single 100-ft, 16 AWG outdoor-rated extension cord. The cord ran from a garage GFCI outlet, under a wooden deck railing, and across a concrete patio to a 20-ft tall spruce tree. For three days, the display operated normally. On day four, neighbors noticed smoke curling from beneath the deck. Fire crews arrived to find the cord’s midpoint—where it passed under the railing—fully melted. The insulation had carbonized, exposing bare copper that arced intermittently against the damp wood. Investigation revealed the cord was rated for 5 A maximum, but the six strands drew 5.8 A continuously. Ambient temperature hovered near 3°C (37°F), but trapped moisture and restricted airflow beneath the deck prevented heat dissipation. Crucially, the homeowner had coiled the excess 30 ft of cord near the outlet—a tight coil acting as a thermal insulator. The National Fire Protection Association later classified this as an “electrical distribution failure due to sustained over-ampacity and inadequate thermal management.” No injuries occurred, but $42,000 in structural damage resulted—all preventable with proper cord selection and installation practices.

Safe Setup Checklist: Before You Plug In

Follow this verified checklist before connecting any lighting display. Print it. Tape it to your cord storage bin. Use it every season.

- ✅ Calculate total load: Add the amperage (not wattage) of every light strand, controller, blower, or accessory. Find amps = watts ÷ volts (e.g., 48W ÷ 120V = 0.4 A). If only wattage is listed, assume 120V nominal unless specified otherwise.

- ✅ Select cord gauge by length and load: Use 14 AWG for loads > 10 A or runs > 50 ft; 12 AWG for > 15 A or > 100 ft. Never use 16/18 AWG for permanent outdoor displays.

- ✅ Limit daisy-chaining to zero: One cord only—from outlet to first light plug. Use a heavy-duty, multi-outlet power strip (UL 1449 listed) rated for outdoor use and your total load.

- ✅ Uncoil completely: Never operate a cord while coiled, wrapped, or bundled—even briefly. Lay flat in open air.

- ✅ Verify GFCI protection: All outdoor circuits must be GFCI-protected. Test GFCIs monthly using the TEST button.

- ✅ Inspect physically: Discard any cord with cracked, stiff, or discolored insulation; bent, loose, or corroded prongs; or warm spots after 10 minutes of operation.

Do’s and Don’ts: Extension Cord Safety Comparison

| Action | Do | Don’t |

|---|---|---|

| Cord Selection | Use 12 or 14 AWG, SJTW-rated (outdoor, oil-resistant, thermoplastic) cords labeled “Heavy Duty” or “Commercial Grade.” | Use 16 or 18 AWG indoor cords—even if “outdoor-rated”—for permanent lighting setups. |

| Connection Method | Plug all strands directly into a single UL-listed outdoor power strip with built-in circuit breaker (e.g., 15 A thermal-magnetic). | Daisy-chain more than one extension cord—or plug a power strip into an extension cord. |

| Placement & Ventilation | Lay cords flat on dry grass, concrete, or decking. Elevate off damp ground using cord risers or bricks. | Run cords under rugs, carpets, doors, or furniture—or coil excess length for storage while energized. |

| Monitoring | Touch-test cord every 30 minutes for first 2 hours. If warm beyond ambient temp, unplug immediately and recalculate load. | Assume “no smell, no smoke” means safe. Thermal damage often occurs silently before visible signs appear. |

Expert Insight: What Electrical Inspectors See on Site

“Over 68% of holiday-related electrical violations I cite involve extension cords operating beyond their thermal rating—not because people are reckless, but because they don’t know how to read a cord’s label. That ‘13 A’ stamped near the plug? It’s only valid for 25 feet. At 100 feet, it’s likely half that. And if the cord’s been stored in an attic for 11 months, its insulation has already aged 2–3 years prematurely. Always treat extension cords as temporary solutions—not permanent wiring.”

— Carlos Mendez, Licensed Master Electrician & NFPA 70E Certified Inspector, 22 years field experience

Step-by-Step: Building a Safe, Scalable Lighting Circuit

Follow this sequence—no shortcuts—to ensure every connection stays within thermal and code limits:

- Step 1: Audit Your Load

Write down every device: light strands (count bulbs + type), timers, controllers, inflatables, etc. Look for labels showing “A” or “W.” Convert all to amps. Total them. - Step 2: Determine Max Run Length

Measure distance from outlet to farthest light. Add 10% for routing inefficiency. Round up to nearest 25 ft increment (e.g., 62 ft → 75 ft). - Step 3: Select Cord Gauge

Consult NEC Table 400.5(A)(3) or UL standards: For ≤ 5 A / ≤ 50 ft → 16 AWG (not recommended); 5–10 A / ≤ 100 ft → 14 AWG; 10–15 A / ≤ 150 ft → 12 AWG. - Step 4: Choose a Distribution Hub

Buy a UL-listed, outdoor-rated power strip with individual switches and a resettable 15 A circuit breaker. Avoid “surge protectors” marketed for electronics—they lack thermal overcurrent protection for lighting loads. - Step 5: Install & Verify

Uncoil cord fully. Plug into GFCI outlet. Plug hub into cord. Connect lights to hub—not cord. Turn on one strand. Check cord temperature after 10 min. Repeat, adding one strand every 10 min until all are live. If cord warms beyond ambient after full load, reduce strands or upgrade cord.

FAQ: Common Questions Answered

Can I use a heavy-duty 12 AWG cord for 200+ LED lights?

Yes—if total load stays below 15 A and cord length is ≤ 150 ft. But verify: 200 premium LED micro-strands may draw only 1.2 A total; 200 budget LED strands with inefficient drivers could pull 3.5 A. Always measure actual draw with a clamp meter if uncertain.

Why do cords heat up more at the plug end than the middle?

Higher resistance at connection points. Plugs and receptacles introduce contact resistance—exacerbated by oxidation, dirt, or loose fit. That localized resistance converts more electrical energy into heat right where insulation is thinnest and most vulnerable.

Is it safe to cover a warm cord with snow to “cool it down”?

No—this is extremely dangerous. Snow melts into water, creating a conductive path. Wet insulation can fail catastrophically, leading to shock or short-circuit arcing. If a cord is warm, unplug it immediately. Do not attempt passive cooling.

Conclusion

Extension cords heat up with multiple light strands not because electricity is inherently unsafe—but because physics demands respect. Resistance, current, time, and environment interact predictably. When you understand those interactions—not as abstract concepts, but as measurable, observable forces—you gain authority over risk. You stop guessing whether “it’s probably fine” and start verifying with numbers, standards, and tactile feedback. You replace tradition with evidence-based practice. This holiday season, commit to one change: calculate your load. Choose the right cord. Uncoil it fully. Touch-test it. Share this knowledge—not just with family, but with neighbors, HOA boards, and community groups. Because preventing an electrical fire isn’t about perfection; it’s about consistency, awareness, and refusing to normalize warmth where there should only be cool, quiet operation. Your home, your memories, and your peace of mind are worth that level of care.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?