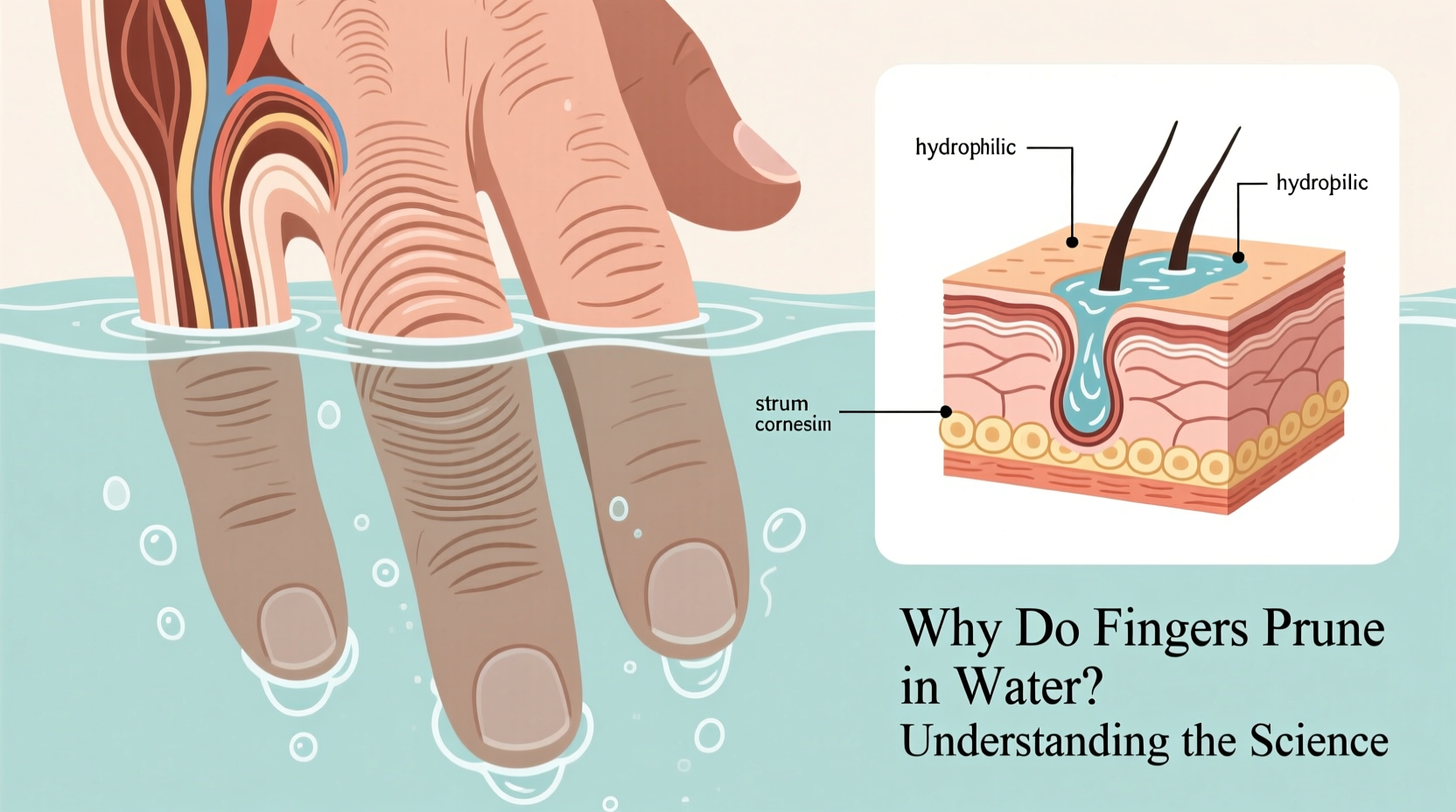

For decades, many believed that the wrinkling of fingers and toes after prolonged exposure to water was simply the result of skin absorbing moisture—like a sponge swelling and folding. But modern research reveals a far more fascinating story. Far from being passive swelling, finger pruning is an active, neurologically controlled process with evolutionary advantages. This article explores the real science behind why fingers wrinkle in water, how it benefits us, and what it says about our body’s remarkable adaptability.

The Myth of Passive Water Absorption

It’s intuitive to assume that when fingers wrinkle in water, they’re just soaking up liquid like paper. After all, keratin—the protein in skin—does absorb water, causing cells to swell. However, this explanation falls short under scrutiny. Studies show that people with nerve damage in their fingers don’t experience pruning, even after long immersion. If swelling were purely due to water absorption, nerve function wouldn’t matter.

This critical observation led scientists to reconsider: pruning isn’t passive—it’s regulated by the nervous system. The autonomic nervous system constricts blood vessels beneath the skin, reducing volume in the fingertip. This internal shrinkage pulls the overlying skin into grooves, creating the familiar pruned appearance.

How the Pruning Mechanism Works

The process begins within minutes of water exposure. Nerve signals trigger vasoconstriction—narrowing of blood vessels—in the fingertips. As blood flow decreases, the tissue volume drops slightly. Because the skin remains attached at certain points, it folds into a pattern of ridges and channels designed to improve grip.

This response is unique to primates and some other mammals, suggesting it evolved for functional reasons. It doesn’t occur uniformly across the body; only on the palms and soles, which are crucial for manipulation and traction.

Interestingly, the effect works best in warm water. Cold water can impair nerve signaling, delaying or preventing pruning. Similarly, very hot water may damage surface receptors, disrupting the signal cascade.

“Finger wrinkling is one of the clearest examples of the body using the nervous system to alter skin structure for improved performance.” — Dr. Mark Changizi, Cognitive Scientist and Evolutionary Biologist

Evolutionary Advantage: Better Grip in Wet Conditions

In 2013, a landmark study published in *Biology Letters* tested the hypothesis that pruned fingers enhance grip on wet objects. Volunteers moved wet marbles from one container to another—some with pruned fingers, others with dry, unwrinkled hands. Those with pruned fingers completed the task significantly faster and with fewer slips.

The pattern of wrinkles functions like tire treads, channeling water away from the contact surface. This drainage system reduces hydroplaning and increases direct contact between skin and object, improving friction and control.

From an evolutionary standpoint, this adaptation would have been highly beneficial. Early humans foraging in rainy environments or handling wet tools, fruits, or stones would gain a mechanical advantage from pruned fingertips. It likely improved survival during food gathering, tool use, and climbing in damp conditions.

Practical Implications of Enhanced Wet Grip

Even today, this trait can be useful. Think of picking up a slippery glass in the shower or handling groceries in the rain. The body prepares itself—automatically optimizing hand function for wet scenarios without conscious effort.

| Situation | Without Pruning | With Pruning |

|---|---|---|

| Handling wet tools | Higher risk of slipping | Better grip and control |

| Walking on wet surfaces | Reduced foot traction | Toes prune, improving balance |

| Reaching for submerged objects | Frequent fumbling | Faster, more accurate retrieval |

Medical and Neurological Significance

Because finger pruning depends on intact nerve pathways and vascular response, it serves as a simple, non-invasive indicator of nervous system health. Doctors sometimes use the “water immersion test” to assess nerve function, particularly in patients suspected of having peripheral neuropathy, Parkinson’s disease, or Raynaud’s phenomenon.

A lack of pruning can point to autonomic dysfunction. For example, individuals with diabetes-related nerve damage often fail to develop wrinkles after water exposure. Similarly, those with carpal tunnel syndrome may show delayed or asymmetrical pruning in affected hands.

Step-by-Step: The Finger Pruning Timeline

- 0–2 minutes: Fingers enter water; no visible change.

- 3–5 minutes: Nerves detect prolonged moisture; signals sent to blood vessels.

- 5–7 minutes: Vasoconstriction begins; fingertip volume starts decreasing.

- 8–10 minutes: Skin folds form distinct ridges—pruning becomes visible.

- 10–30 minutes: Wrinkles stabilize; optimal groove pattern achieved.

- After removal: Blood flow resumes; fingers return to normal in 20–30 minutes.

Tips for Observing and Understanding Your Body’s Response

- Use lukewarm water—extreme temperatures may interfere with nerve signals.

- Compare both hands; asymmetry could suggest localized nerve issues.

- Note how long it takes for wrinkles to appear and disappear.

- Avoid testing if you have open cuts or infections.

- Don’t rely solely on this test—consult a professional if concerned.

Mini Case Study: Detecting Early Neuropathy

John, a 58-year-old warehouse worker with type 2 diabetes, noticed his fingers weren’t wrinkling during showers. At first, he dismissed it as aging. But when he mentioned it during a routine check-up, his doctor ordered a nerve conduction study. The results confirmed early-stage peripheral neuropathy. With timely intervention—including better glucose control and protective footwear—John avoided further complications. His lack of pruning was an early red flag that prompted life-changing care.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does everyone’s fingers prune in water?

Most healthy individuals experience finger pruning, but those with certain neurological or circulatory conditions may not. Absence of pruning can be a medical sign worth investigating.

Can you speed up the pruning process?

No safe method speeds it up. Warm water helps, but scrubbing or damaging the skin won’t trigger faster wrinkling. The process is governed by internal physiology, not surface treatment.

Why don’t other parts of the body wrinkle the same way?

Only the palms and soles have the specialized nerve endings and thick epidermis needed for functional pruning. Elsewhere, skin swells without forming structured channels because there’s no evolutionary benefit.

Conclusion: A Small Wonder of Human Design

Finger pruning is more than a curious quirk—it’s a finely tuned biological adaptation shaped by evolution. What once seemed like a trivial side effect of bath time is now understood as a sophisticated mechanism to improve dexterity in wet environments. It reflects the body’s ability to dynamically respond to external conditions through neural control, offering both practical advantage and diagnostic insight.

Understanding this process deepens appreciation for the complexity of human physiology. It reminds us that even the smallest bodily reactions often have purpose and precision behind them.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?