Goosebumps—those tiny bumps that rise on your skin when you're cold, scared, or deeply moved—are a universal human experience. Yet, despite their familiarity, few understand the biological mechanisms behind them or realize that not everyone experiences them with the same intensity. This reflex, formally known as piloerection or cutis anserina, is more than just a quirky bodily reaction. It's a window into our evolutionary past, nervous system function, and even emotional sensitivity. Understanding why we get goosebumps—and who is more likely to feel them—reveals fascinating insights about human physiology and individual differences.

The Biology of Goosebumps: A Reflex Rooted in Evolution

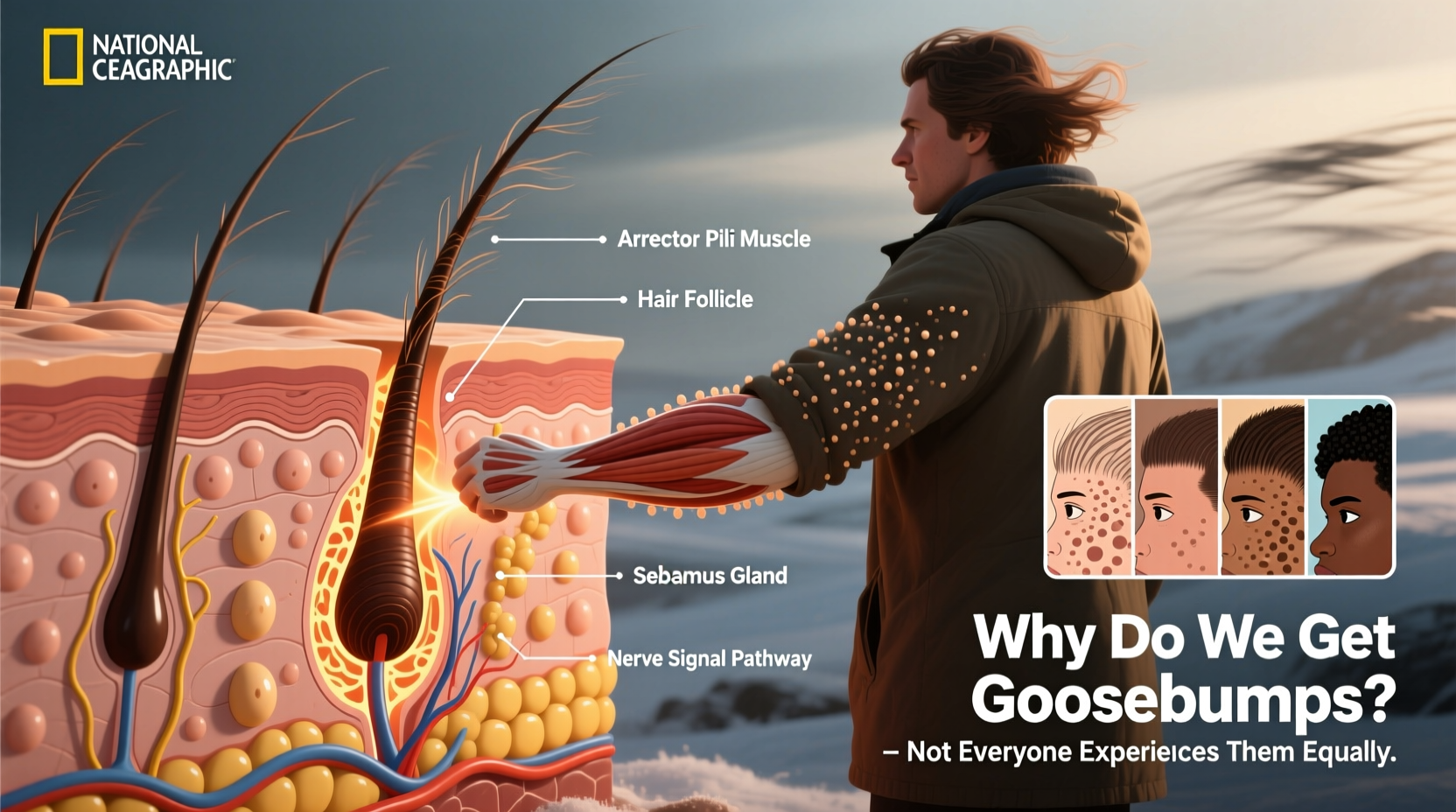

Goosebumps occur when tiny muscles at the base of each hair follicle—called arrector pili muscles—contract, causing hairs to stand upright. This reaction is triggered by the sympathetic nervous system, which governs involuntary responses such as heart rate, digestion, and stress reactions. When stimulated, these muscles pull on the skin, creating a small bump around each hair.

In animals with thick fur, this response serves clear survival purposes. For instance, a cat fluffing its coat when threatened appears larger and more intimidating. Similarly, raising fur traps air close to the skin, providing insulation during cold exposure. Humans, however, have far less body hair, so the functional benefit of goosebumps is minimal today. Yet, the reflex remains—a vestige of our evolutionary ancestry.

“Piloerection in humans is a phylogenetic leftover. While it no longer serves a thermoregulatory or defensive purpose, it persists because the neural circuitry is still intact.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Neurophysiologist, University of Edinburgh

Triggers of Goosebumps: Cold, Emotion, and Beyond

While cold temperatures are the most obvious cause of goosebumps, they are far from the only trigger. The phenomenon manifests across three primary contexts:

- Thermal stimulation: Exposure to cold activates the sympathetic nervous system, prompting vasoconstriction (narrowing of blood vessels) and piloerection in an attempt to conserve heat.

- Emotional arousal: Intense emotions such as awe, fear, nostalgia, or joy can provoke goosebumps. These are often linked to music, art, personal memories, or powerful speeches.

- Psychological stimuli: Sudden fright, suspenseful moments in films, or spiritual experiences may also elicit the response.

Interestingly, emotionally induced goosebumps are more complex neurologically. They involve brain regions associated with reward processing, such as the nucleus accumbens and the anterior insula. Studies using fMRI scans show increased activity in these areas during peak emotional moments that trigger physical reactions like shivers or goosebumps.

Individual Differences: Do All People Experience Goosebumps Equally?

No two people experience goosebumps in exactly the same way. Some individuals report frequent and intense episodes, especially during emotional stimuli, while others rarely—if ever—feel them. Several factors contribute to this variability:

- Genetics: Variations in adrenergic receptor sensitivity can influence how strongly someone reacts to stimuli that trigger the sympathetic nervous system.

- Neurological wiring: Differences in brain connectivity, particularly between emotional centers and autonomic pathways, affect responsiveness.

- Personality traits: Research links frequent emotional goosebumps to higher levels of openness to experience, empathy, and absorption—the tendency to become deeply immersed in sensory or imaginative experiences.

- Age: Children and adolescents tend to report more frequent goosebumps than older adults, possibly due to heightened emotional reactivity and hormonal fluctuations.

- Cultural and environmental influences: Upbringing, exposure to art and music, and social conditioning may shape one’s susceptibility to emotionally triggered piloerection.

A 2020 study published in *Psychophysiology* found that nearly 30% of participants reported never experiencing music-induced goosebumps, while another 20% experienced them weekly or more. This wide distribution underscores that goosebump frequency is not a measure of emotional capacity but rather reflects individual neurobiological profiles.

Who Is More Likely to Get Emotional Goosebumps?

| Factor | Associated With Higher Likelihood | Associated With Lower Likelihood |

|---|---|---|

| Personality | High openness, empathy, absorption | Low emotional expressivity, high alexithymia |

| Music Engagement | Frequent listeners, musicians, composers | Occasional listeners, non-musical individuals |

| Age Group | Teens and young adults | Adults over 65 |

| Neurological Sensitivity | Strong autonomic reactivity | Reduced sympathetic response |

| Mental Health | Anxiety disorders (heightened arousal) | Depression (blunted emotional response) |

Mini Case Study: The Power of Music and Memory

Sophie, a 28-year-old graphic designer, recalls the first time she felt goosebumps during a live concert. At a performance of Samuel Barber’s *Adagio for Strings*, played in memory of a late family member, she described a sudden wave of chills spreading from her neck down her arms. “It wasn’t just sadness,” she said. “It was like my body was responding before my mind could catch up.”

Her experience is typical of what researchers call \"aesthetic chills\"—intense physiological reactions to beauty or meaning. Sophie had always been sensitive to music, but this moment marked a turning point in how she understood her own emotional landscape. Since then, she’s noticed that certain film scores, poetry readings, and even acts of kindness can produce similar sensations.

What makes Sophie’s case instructive is not the uniqueness of her reaction, but its clarity. Her heightened sensitivity aligns with psychological profiles that score high on trait absorption and emotional contagion. For her, goosebumps aren’t anomalies—they’re signals of deep engagement with the world.

Practical Implications: Can You Increase Your Sensitivity?

While you can’t fundamentally change your genetic predisposition, there are ways to become more attuned to stimuli that might trigger goosebumps. These practices don’t guarantee physical reactions, but they can enhance emotional awareness and sensory appreciation:

Checklist: Enhancing Emotional and Sensory Awareness

- Practice active listening to music—focus on dynamics, instrumentation, and emotional arc.

- Engage in reflective journaling after moving experiences (films, books, conversations).

- Expose yourself to diverse forms of art: poetry, dance, visual exhibitions.

- Reduce background noise and distractions to deepen immersion.

- Try mindfulness exercises to improve body-mind connection.

- Revisit meaningful memories through photos or letters to evoke emotional resonance.

- Attend live performances where collective emotion amplifies individual response.

These habits won’t force goosebumps, but they create conditions where profound emotional moments are more likely to occur—and be felt physically.

When the Absence of Goosebumps Might Signal Something Else

Not experiencing goosebumps is entirely normal for many people. However, in rare cases, a complete lack of piloerection—even in extreme cold or emotional situations—could indicate underlying medical conditions. These include:

- Autonomic neuropathy: Damage to nerves regulating involuntary functions, often seen in diabetes or autoimmune disorders.

- Hypothyroidism: Reduced metabolic activity can blunt autonomic responses.

- Certain medications: Beta-blockers and some antidepressants may suppress sympathetic nervous system activity.

- Skin atrophy: Aging or dermatological conditions affecting hair follicles and muscle integrity.

If someone notices a sudden loss of previously experienced goosebumps—especially alongside other symptoms like temperature intolerance or fatigue—it may warrant consultation with a neurologist or endocrinologist.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can animals other than humans get goosebumps?

Yes, most mammals exhibit piloerection. In furry animals, it serves practical roles like insulation and threat display. Even aquatic mammals like seals show limited versions of the reflex, though its function is reduced.

Why do some songs give me goosebumps but others don’t?

Music-induced goosebumps depend on both the composition and your personal associations. Unexpected harmonies, crescendos, lyrical relevance, or nostalgic connections increase the likelihood. Individual taste and prior experiences shape which pieces resonate deeply.

Are goosebumps a sign of being “more emotional” than others?

Not necessarily. Frequent goosebumps may reflect higher emotional sensitivity or a reactive nervous system, but absence doesn’t imply emotional shallowness. Emotional depth expresses in many ways beyond physiological responses.

Conclusion: Listening to the Language of the Body

Goosebumps are a quiet yet powerful testament to the intricate link between mind, body, and environment. Whether sparked by a winter breeze or a soul-stirring melody, they remind us that our bodies still carry ancient instincts and profound emotional capacities. While not everyone feels them with equal intensity, their presence—or absence—offers valuable clues about individual biology and inner life.

Understanding goosebumps goes beyond curiosity; it invites deeper self-awareness. By paying attention to these fleeting physical signals, we learn to appreciate the subtlety of human experience. Whether you're someone who shivers at the first note of a favorite song or someone who rarely notices the sensation, recognizing the science behind it enriches your relationship with your own body.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?