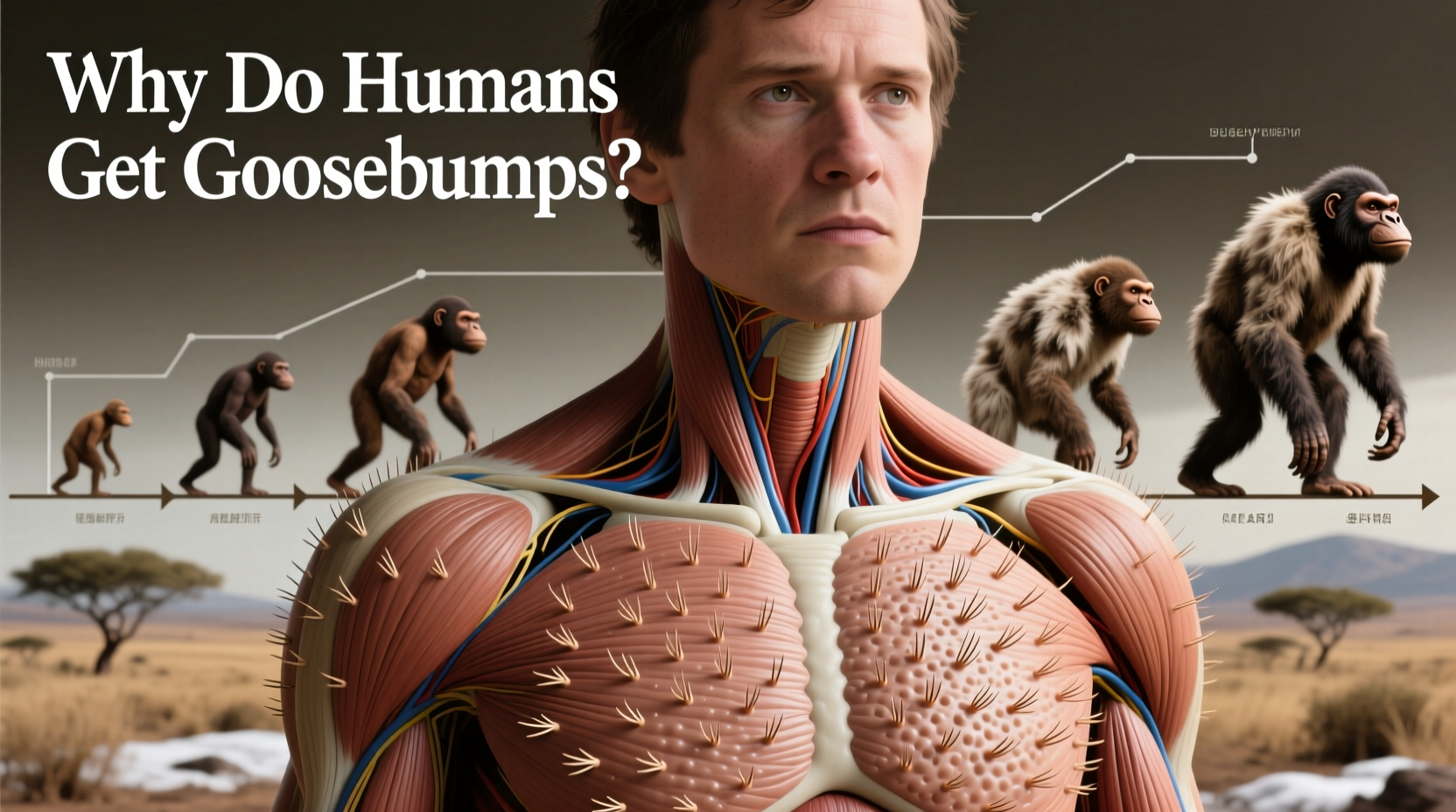

Goosebumps—those tiny bumps that rise on your skin when you're cold, scared, or deeply moved—are more than just a fleeting physical reaction. They are a living echo of our evolutionary past, a biological reflex embedded in our nervous system long before modern humans walked the Earth. While today they serve little practical purpose in thermoregulation or threat display, their persistence reveals a fascinating story about adaptation, emotion, and the deep wiring of the human body.

This involuntary response, technically known as piloerection or cutis anserina, is triggered by the sympathetic nervous system—the same network responsible for the fight-or-flight response. Understanding why we still experience goosebumps requires peeling back layers of biology, psychology, and evolutionary history to uncover how ancient survival mechanisms continue to shape our bodies in subtle but meaningful ways.

The Biological Mechanism Behind Goosebumps

At the core of the goosebump phenomenon is a small muscle called the arrector pili, attached to each hair follicle. When stimulated by signals from the autonomic nervous system—specifically the sympathetic branch—this muscle contracts, pulling the hair upright and causing the surrounding skin to bunch up into a small bump.

This process is rapid and unconscious. It begins when the brain detects a stimulus: a sudden drop in temperature, a surge of adrenaline during fear, or even an emotionally powerful piece of music. The hypothalamus processes these inputs and activates the sympathetic nervous system, which sends electrical impulses down nerves to the arrector pili muscles throughout the skin.

In animals with thick fur, such as cats or bears, this reaction has a clear function: fluffing up the coat traps air close to the skin, creating an insulating layer that conserves heat. Similarly, when threatened, raising the fur makes an animal appear larger and more intimidating—a defensive bluff used by many mammals when confronted by predators.

Evolutionary Origins: From Fur to Feelings

Humans, of course, lack the dense pelage of our furry ancestors. Our relatively sparse body hair means that erecting it provides negligible insulation or intimidation value. So why does this reflex persist?

The answer lies in evolutionary inertia. Traits don’t disappear simply because they no longer serve a primary function—especially if they’re linked to broader physiological systems that *are* still vital. The goosebump reflex is part of a larger stress and arousal network that includes increased heart rate, pupil dilation, and adrenaline release. These responses were crucial for early humans navigating predator-filled environments, fluctuating climates, and complex social hierarchies.

Anthropologists believe that piloerection was once functional in hominid ancestors who had significantly more body hair. As humans evolved to rely on clothing and shelter for warmth, and on tools and group cooperation for defense, the need for piloerection diminished. Yet the neural circuitry remained intact, repurposed over time to respond not only to environmental threats but also to emotional and sensory experiences.

“Goosebumps are a vestige of our mammalian heritage—a whisper from a time when every shiver could mean survival.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Evolutionary Biologist, University of Edinburgh

Emotional Triggers: Why Music and Memories Cause Goosebumps

One of the most intriguing aspects of goosebumps is their association with strong emotions. Many people report getting them while listening to moving music, watching a powerful film scene, or recalling a poignant memory. This phenomenon, often called \"frisson,\" occurs in approximately 50–80% of the population, depending on cultural and individual differences.

Neuroimaging studies show that emotionally induced goosebumps activate regions of the brain associated with reward processing, including the nucleus accumbens and the ventral tegmental area—areas rich in dopamine neurons. When a piece of music builds to a crescendo or a story reaches its emotional peak, the brain releases dopamine, creating a sensation akin to pleasure or awe. This neurochemical surge can trigger the sympathetic nervous system, leading to physical manifestations like chills, tears, and yes—goosebumps.

Researchers suggest that this response may have evolved as a way to reinforce socially bonding experiences. Shared emotional moments—such as communal singing, storytelling, or ritual ceremonies—likely strengthened group cohesion in early human societies. The physical sensation of frisson may have acted as a feedback loop, making individuals more likely to seek out and remember these unifying events.

| Trigger Type | Biological Pathway | Evolutionary Purpose (Original) | Modern Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cold exposure | Sympathetic nervous system → arrector pili contraction | Insulation via trapped air in fur | Minimal; mostly obsolete |

| Fear or surprise | Adrenaline release → piloerection | Appearing larger to deter threats | Part of broader stress response |

| Emotional stimuli (music, art) | Dopamine release → autonomic activation | Reinforcing social bonding | Enhances emotional resonance |

Goosebumps and Social Communication

Though we can't puff up like a startled cat, humans still use subtle physiological cues to communicate internal states. Goosebumps, while not visible to others under normal conditions, may play a role in self-awareness and emotional regulation. The sensation acts as a bodily marker of intense feeling, helping individuals recognize and process moments of awe, fear, or beauty.

In some cultures, the experience of \"getting chills\" from music or spiritual experiences is interpreted as a sign of transcendence or connection to something greater. This suggests that the goosebump response, though physically minor, carries symbolic weight in human cognition and culture.

Interestingly, people who score higher on personality traits like openness to experience are more likely to experience frisson. This correlation supports the idea that goosebumps are not just random glitches but meaningful indicators of sensitivity to aesthetic and emotional stimuli—traits that may have conferred social advantages in ancestral groups where storytelling, ritual, and music played central roles.

A Real-Life Example: The Power of Live Music

Consider Sarah, a 34-year-old teacher who attends a live orchestral performance of Samuel Barber’s *Adagio for Strings*. As the final notes swell, she feels a wave of cold ripple down her arms, followed by raised hairs and a lump in her throat. She isn’t cold, nor afraid—yet her body reacts as if under profound duress or wonder.

What’s happening? Her auditory cortex processes the music, identifying patterns of tension and resolution. The limbic system interprets this as emotionally significant, triggering dopamine release. This, in turn, activates the autonomic nervous system, producing goosebumps. For Sarah, this moment isn’t just beautiful—it’s embodied. Her body confirms what her mind already knows: this experience matters.

This kind of visceral response likely strengthened social bonds in early human communities. Those who felt deeply during group rituals may have been more committed to collective identity, increasing cooperation and survival odds. Today, we see echoes of this in concerts, religious services, and public memorials—events designed to elicit shared emotional peaks, often accompanied by widespread reports of chills and goosebumps.

Practical Insights: Harnessing the Goosebump Response

While you can’t control when goosebumps occur, understanding their triggers can help you cultivate more meaningful daily experiences. Since they’re linked to emotional intensity and attentional focus, certain practices increase the likelihood of experiencing them—and potentially deepen your engagement with art, nature, and relationships.

Checklist: How to Invite More Emotionally Powerful Moments

- Seek out novel or unpredictable artistic experiences (e.g., unfamiliar genres of music or experimental films)

- Listen to music with headphones to enhance immersion and auditory detail

- Reflect on personal memories while engaging with art or nature

- Attend live performances where collective emotion amplifies individual response

- Practice mindfulness to heighten awareness of bodily sensations during emotional moments

Common Misconceptions About Goosebumps

Despite being a universal experience, several myths surround goosebumps. One common belief is that only “sensitive” people get them. In reality, prevalence varies due to neurological and psychological factors—not weakness or excess emotionality. Another misconception is that goosebumps are purely psychological. While emotions can trigger them, the pathway is firmly rooted in physiology: nerve signals, muscle contractions, and hormone release.

Some also assume that since humans have little body hair, the reflex is entirely useless. But recent research suggests otherwise. Even minimal piloerection might influence sweat evaporation or tactile sensitivity, though these effects remain understudied. Moreover, the reflex serves as a biomarker for autonomic activity, useful in clinical settings for assessing nervous system function.

FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions

Can everyone experience goosebumps?

Most people can experience goosebumps from cold or fear, but not everyone feels them in response to emotions like music or awe. Estimates suggest 50–80% of people experience frisson, with variation based on personality, musical training, and neural sensitivity.

Are goosebumps a sign of good health?

Yes, in general. Their presence indicates a functioning sympathetic nervous system. A complete absence—especially in response to cold or stress—could signal underlying neurological issues and should be evaluated by a healthcare provider.

Why do some songs give me chills while others don’t?

Songs that induce chills often contain elements like sudden volume changes, harmonic surprises, melodic anticipation, or personal associations. Your brain rewards you with dopamine when expectations are met or violated in compelling ways, triggering the autonomic response that leads to goosebumps.

Conclusion: Listening to the Whisper of Evolution

Goosebumps are more than a quirky bodily reaction—they are a bridge between our ancient past and present emotional life. Born from the needs of furred mammals trying to survive in a dangerous world, this reflex has been repurposed by evolution to mark moments of deep human significance. Whether you're standing in the cold, facing a threat, or moved by a symphony, your body responds in a language older than words.

Recognizing the evolutionary roots of goosebumps doesn’t diminish their power—it enhances it. Each time you feel your skin prickle, you’re experiencing a direct line to the instincts and emotions that shaped our species. These tiny eruptions are reminders that we are not just rational minds, but embodied creatures wired for connection, survival, and awe.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?