Fingerprints are one of the most distinctive biological features of human beings. No two individuals—except identical twins—have the same fingerprints, and even among identical twins, subtle differences exist. This level of individuality has made fingerprints invaluable in forensic science, biometric identification, and personal security systems. But beyond their practical applications, a deeper question arises: Why did evolution shape such intricate, unique patterns on our fingertips? What is the evolutionary advantage of having distinct fingerprints, and how did this trait become so universally consistent across the human species?

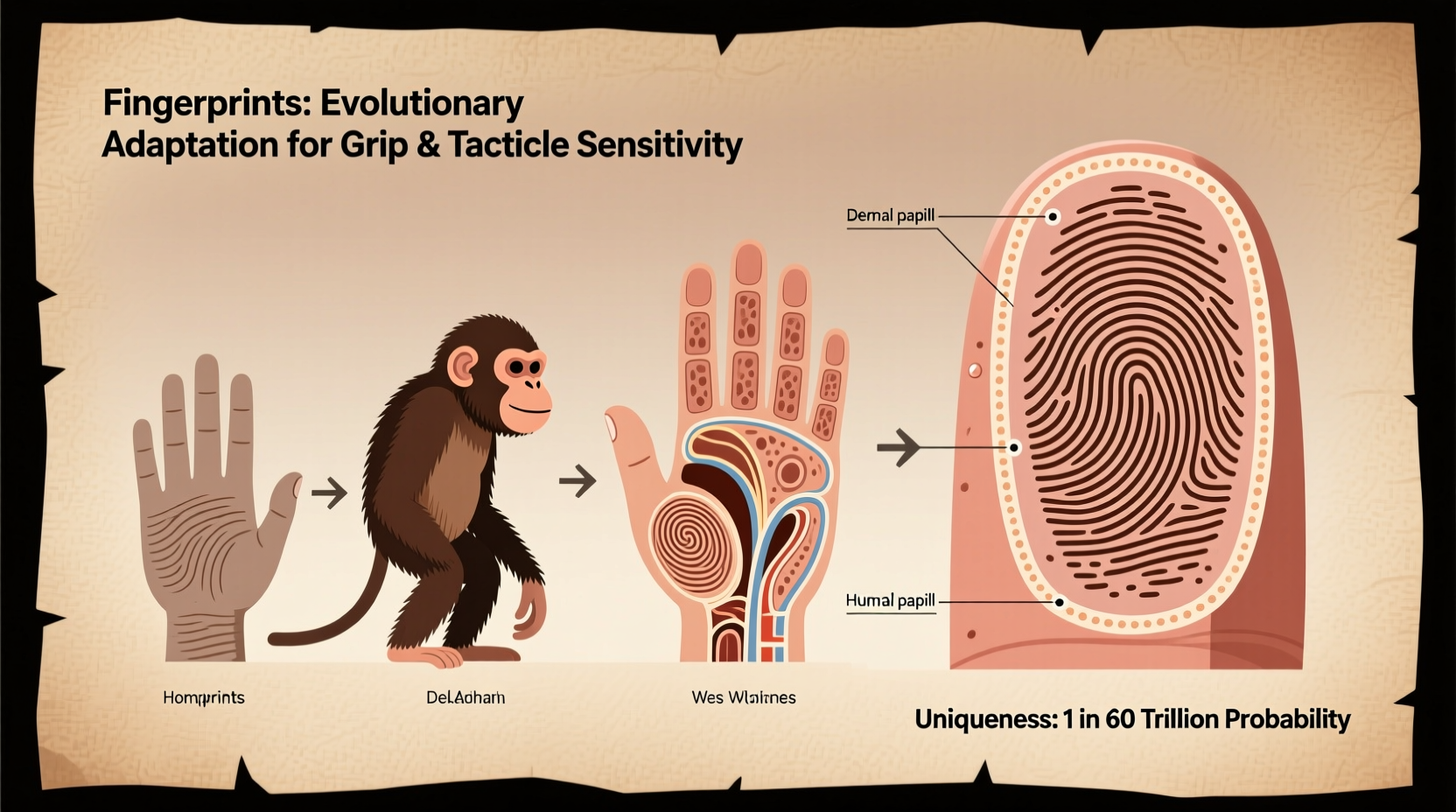

The answer lies at the intersection of biology, evolution, and functional adaptation. Fingerprints are not random skin patterns; they are the result of millions of years of refinement, shaped by natural selection to enhance grip, tactile sensitivity, and environmental interaction. Understanding their origin and purpose reveals not only how humans evolved to manipulate tools and navigate complex environments but also why these patterns remain individually unique.

The Biological Basis of Fingerprint Formation

Fingerprints begin forming during fetal development, around the 10th to 15th week of gestation. They arise from the interaction between the epidermis (outer skin layer) and the dermal papillae (the layer beneath). As the fingers grow, mechanical stresses cause the skin layers to buckle and fold into ridges. These ridges form specific patterns—loops, whorls, and arches—that are stabilized before birth and remain unchanged throughout life, barring injury or disease.

While genetics play a role in determining the general pattern type (e.g., whether someone tends to have loops or whorls), the exact configuration of ridge endings, bifurcations, and minutiae points is influenced by random developmental factors such as amniotic fluid pressure, blood supply variations, and finger position in the womb. This combination of genetic guidance and stochastic (random) physical forces ensures that even genetically identical individuals develop non-identical prints.

Evolutionary Advantages of Fingerprints

The persistence of fingerprints across all human populations—and in many primates—suggests strong evolutionary benefits. Scientists have proposed several key functions that explain why these ridges were naturally selected over smooth fingertips.

Enhanced Grip and Friction Control

One of the primary evolutionary purposes of fingerprints is to improve grip. The ridges act like tire treads, channeling away moisture and increasing surface contact with dry objects. Studies have shown that fingerprints can increase friction when handling rough surfaces and reduce slippage on wet or smooth materials by creating micro-channels that disperse liquid.

This function would have been crucial for early hominins who relied on precise manipulation of tools, climbing trees, and carrying food or infants. A better grip meant greater survival odds—whether avoiding a fall from a branch or securely wielding a stone tool during hunting.

Sensory Enhancement and Tactile Feedback

Fingerprints also amplify tactile perception. The ridges are densely packed with nerve endings, particularly Meissner’s corpuscles, which respond to light touch and vibrations. When fingertips glide over a surface, the ridges vibrate at specific frequencies, enhancing the brain’s ability to detect texture, edges, and fine details.

“Fingerprints function as biological amplifiers—they turn subtle surface textures into detectable signals for the nervous system.” — Dr. Sarah Langford, Neurobiologist, University of Bristol

This heightened sensitivity would have provided early humans with a significant advantage in identifying edible plants, detecting predators by touch in low-light conditions, or crafting intricate tools from bone and stone.

Mechanical Protection and Skin Resilience

The ridge structure may also help protect the skin from tearing under stress. By distributing mechanical strain across multiple ridges, the skin becomes more resistant to abrasion and blistering—important for a species that regularly handled rough materials like wood, stone, and animal hides.

Why Are Fingerprints Unique? The Role of Chaos in Development

Even though all humans share the same basic fingerprint types, the minute details—the minutiae—are entirely unique. This individuality stems from what scientists call “developmental noise”: small, unpredictable variations in the uterine environment that influence how ridges form.

Imagine two identical cars rolling off the same assembly line. While their design is identical, tiny differences in temperature, humidity, or robotic calibration lead to microscopic variances. Similarly, two fetuses with identical DNA will experience slightly different pressures, nutrient flows, and movements in the womb. These minute differences cascade into macroscopic changes in fingerprint patterns.

This randomness ensures diversity without requiring additional genetic complexity. Evolution doesn’t need a separate gene for every possible fingerprint—it simply built a system where variation emerges naturally from physical constraints and environmental input.

Uniqueness in Identical Twins: A Case Study

Identical twins share 100% of their DNA, yet their fingerprints are never exactly the same. Consider the case of Maria and Elena, monozygotic twins raised in the same household. Forensic examiners analyzing their prints found that while both had dominant loop patterns on their right index fingers, the placement of ridge endings and bifurcations differed significantly. One had a short ridge ending 0.3 mm higher than the other—an imperceptible difference to the naked eye, but enough to rule out a match in automated fingerprint identification systems (AFIS).

This real-world example underscores that genetics set the stage, but developmental environment writes the final script. It also explains why biometric systems rely on minutiae points rather than broad pattern types—they capture the true essence of uniqueness.

Applications of Fingerprint Uniqueness in Modern Society

The evolutionary quirk of fingerprint individuality has become a cornerstone of modern technology and law enforcement. From unlocking smartphones to solving crimes, the reliability of fingerprints rests on their permanence and distinctiveness.

| Application | How Fingerprints Are Used | Reliability Factor |

|---|---|---|

| Forensics | Link suspects to crime scenes via latent prints | High – if sufficient ridge detail is recovered |

| Biometric Security | Authenticate identity for phones, laptops, and border control | Very High – multi-point verification reduces false matches |

| Medical Diagnosis | Analyze dermatoglyphics to detect genetic disorders (e.g., Down syndrome) | Moderate – used as screening tool, not definitive |

| Historical Records | Used in census and immigration since late 1800s | Permanent – unlike names or documents, prints don’t change |

Despite advances in facial recognition and iris scanning, fingerprints remain one of the most trusted biometric identifiers due to their high entropy (information density) and resistance to spoofing.

Common Misconceptions About Fingerprints

- Myth: People can be identified solely by fingerprint pattern type (loop, whorl, arch).

- Fact: Pattern type is too common—over 60% of people have loops. Identification relies on minutiae, not general shape.

- Myth: Fingerprints can be permanently changed through surgery or burns.

- Fact: Superficial damage heals with original patterns; deep scarring may alter prints but creates new identifying features.

- Myth: Animals have the same kind of fingerprints as humans.

- Fact: Some primates (like gorillas and chimpanzees) have similar ridge patterns, but none exhibit the same level of individual complexity or forensic utility.

Step-by-Step: How Fingerprints Are Analyzed in Forensics

When a fingerprint is collected from a crime scene, it undergoes a rigorous analysis process before being matched to a suspect. Here’s how experts proceed:

- Collection: Latent prints are lifted using powder, chemicals (like cyanoacrylate fuming), or alternate light sources.

- Classification: Analysts determine the general pattern type (loop, whorl, arch) to narrow down search parameters.

- Minutiae Mapping: Key points such as ridge endings, bifurcations, and dots are marked—typically 12–16 points are needed for a match.

- Digital Comparison: The print is run through AFIS (Automated Fingerprint Identification System) to find potential candidates.

- Manual Verification: A trained examiner visually compares the suspect print with the database match to confirm accuracy.

- Court Presentation: Findings are documented and presented with statistical confidence levels.

This method balances speed and precision, ensuring that matches are both efficient and legally defensible.

FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions

Can two people ever have the same fingerprints?

No conclusive evidence exists of any two individuals—living or dead—having identical fingerprints. The probability of a random match is estimated at 1 in 64 billion, making it statistically near-impossible.

Do fingerprints change over time?

No, the ridge pattern remains the same from infancy to old age. However, temporary swelling, cuts, or dirt can obscure prints. Permanent scarring alters the pattern but introduces new identifying features.

Are fingerprints used in animal identification?

Rarely. While some zoos and research facilities use paw or nose prints for primates or dogs, the lack of standardized minutiae makes them less reliable than microchipping or DNA testing.

Checklist: Understanding Your Own Fingerprints

- ✅ Examine your fingertips with a magnifying glass to identify your dominant pattern (loop, whorl, arch).

- ✅ Take an ink impression or use a smartphone scanner app to visualize ridge flow.

- ✅ Compare prints from both hands—you’ll likely see symmetry in pattern types but differences in minutiae.

- ✅ Research your dermatoglyphics—some studies link certain patterns to hand dominance or sensory sensitivity.

- ✅ Learn how your phone uses capacitive sensing to read ridge-valley contrasts for authentication.

Conclusion: Embracing the Mark of Individuality

Fingerprints are far more than forensic tools or biometric passwords—they are living records of our evolutionary journey. Shaped by necessity, refined by time, and distinguished by chance, they represent a perfect blend of biology and physics. Their uniqueness is not a flaw but a feature: nature’s way of tagging each individual with an unforgeable signature.

Understanding why humans have different fingerprints deepens our appreciation for the subtle mechanisms that define human adaptability. From gripping a stone axe to unlocking a digital device, our fingerprints continue to serve us in ways our ancestors could never have imagined.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?