It’s a common experience: you finish a satisfying meal, only to feel your energy plummet minutes later. Your eyelids grow heavy, your thoughts slow, and all you want is a nap. While many blame this on a “sugar crash,” the truth is more complex. Post-meal fatigue can stem from a combination of physiological processes involving blood sugar, digestion, hormones, and even food choices. Understanding what’s really happening in your body can help you make better dietary decisions and maintain steady energy throughout the day.

The Sugar Crash Myth—And Why It’s Only Partly True

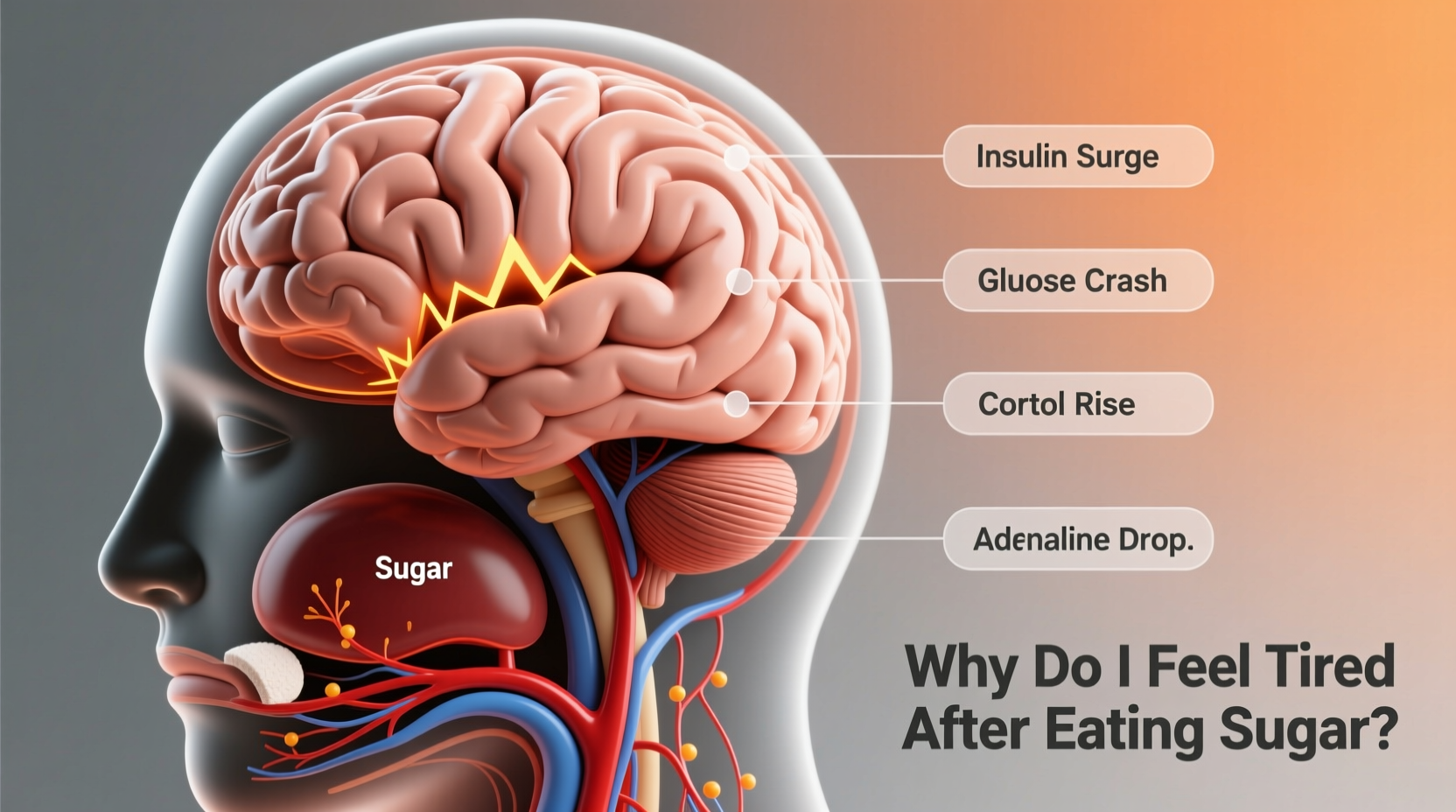

When people say they’re experiencing a “sugar crash,” they’re usually referring to the rapid rise and fall of blood glucose after consuming high-sugar foods. This phenomenon does exist, but it’s not always the primary cause of fatigue after eating.

Here’s how it works: when you eat carbohydrates—especially refined ones like white bread, pastries, or soda—your body quickly breaks them down into glucose. Blood sugar spikes, prompting the pancreas to release insulin to shuttle glucose into cells for energy. But if the spike is too steep, insulin may overcompensate, causing blood sugar to drop below baseline. This hypoglycemic dip can trigger symptoms like fatigue, irritability, brain fog, and hunger.

However, research shows that not everyone experiences this dramatic crash. A 2022 study published in Nature Metabolism found that individual responses to food vary widely based on metabolism, gut microbiome, and lifestyle factors. For some, a banana might cause a sharp drop in energy; for others, it provides sustained fuel.

“Blood sugar fluctuations are real, but labeling every post-meal slump as a ‘sugar crash’ oversimplifies a complex metabolic process.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Endocrinologist and Metabolic Health Specialist

Digestion Itself Can Drain Energy

One overlooked reason for feeling tired after eating has nothing to do with sugar—it’s simply the act of digestion. After a meal, your body redirects blood flow from the brain and muscles to the digestive tract to support nutrient absorption. This shift can reduce alertness and contribute to drowsiness, especially after large or heavy meals.

This effect is amplified by the parasympathetic nervous system, which activates the “rest and digest” mode. When you eat, particularly protein- and fat-rich foods, your body increases production of acetylcholine and other neurotransmitters that promote relaxation. This is a natural, healthy response—but it can be inconvenient if you're trying to stay focused at work.

Hidden Triggers Beyond Sugar

Sugar isn’t the only culprit. Several other dietary and physiological factors can lead to post-meal fatigue:

- Tryptophan-rich foods: Turkey, cheese, eggs, and nuts contain tryptophan, an amino acid used to produce serotonin and melatonin—neurochemicals linked to relaxation and sleep.

- High-fat meals: Fatty foods take longer to digest, requiring more energy and prolonging the “digestive load” on your system.

- Food intolerances: Undiagnosed sensitivities to gluten, dairy, or additives can trigger inflammation and fatigue after eating.

- Dehydration: Many people mistake post-meal sluggishness for tiredness when it’s actually mild dehydration, especially if they drank little water with their meal.

- Alcohol consumption: Even a single glass of wine with dinner can enhance drowsiness due to its depressant effects on the central nervous system.

Moreover, processed foods often contain hidden sugars, unhealthy fats, and artificial ingredients that disrupt metabolic balance. These components can trigger insulin surges, inflammation, and oxidative stress—all contributing to low energy.

What You Eat Matters More Than You Think

The composition of your meal plays a critical role in how you feel afterward. Meals high in refined carbs and low in fiber, protein, or healthy fats are most likely to cause energy swings. In contrast, balanced meals stabilize blood sugar and sustain energy.

Consider the difference between these two breakfasts:

| Meal Type | Example | Energy Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Unbalanced (High-Sugar) | Donut + orange juice | Rapid spike in blood sugar, followed by crash within 1–2 hours. High likelihood of fatigue, cravings, and brain fog. |

| Balanced (Nutrient-Dense) | Oatmeal with nuts, berries, and Greek yogurt | Gradual glucose release due to fiber, protein, and fat. Sustained energy for 3–4 hours with minimal fatigue. |

Fiber slows carbohydrate absorption, preventing sharp insulin spikes. Protein and healthy fats increase satiety and further stabilize blood sugar. Together, they form the foundation of energy-sustaining nutrition.

Real-Life Example: Sarah’s Afternoon Slump

Sarah, a 34-year-old project manager, routinely felt exhausted after her lunch of a turkey sandwich on white bread, chips, and a soda. By 2 PM, she struggled to focus, often needing caffeine or a nap to continue working.

After consulting a nutritionist, she switched to grilled chicken salad with quinoa, avocado, olive oil dressing, and a small apple. She also started drinking water instead of soda. Within a week, her afternoon fatigue diminished significantly. Her energy remained stable, and she no longer needed a daily coffee boost.

The change wasn’t about cutting calories—it was about improving meal quality. The new lunch provided complex carbs, fiber, lean protein, and healthy fats, supporting steady glucose levels and efficient digestion.

Step-by-Step Guide to Prevent Post-Meal Fatigue

If you’re consistently tired after eating, follow this practical plan to identify and correct the root causes:

- Track your meals and energy levels: Keep a food and symptom journal for 3–5 days. Note what you eat, portion sizes, and how you feel 30–60 minutes after eating.

- Reduce refined carbohydrates: Replace white bread, sugary cereals, and processed snacks with whole grains, legumes, and vegetables.

- Balance every meal: Aim for a mix of protein (e.g., chicken, tofu, beans), healthy fats (e.g., avocado, nuts, olive oil), and fiber-rich carbs (e.g., sweet potatoes, broccoli, berries).

- Eat smaller, more frequent meals: Large meals increase digestive demand. Try five smaller meals or three moderate-sized ones with light snacks in between.

- Stay hydrated: Drink water before and during meals. Dehydration can mimic fatigue and impair digestion.

- Move after eating: A 10-minute walk after meals helps regulate blood sugar and stimulates circulation, reducing drowsiness.

- Check for food sensitivities: If fatigue persists despite dietary improvements, consider testing for gluten intolerance, lactose intolerance, or other common triggers.

- Prioritize sleep and stress management: Chronic fatigue may not be meal-related. Poor sleep or high cortisol levels can amplify post-meal tiredness.

When to See a Doctor

Occasional tiredness after a big meal is normal. But if you frequently experience severe fatigue, shakiness, sweating, or confusion after eating, it could signal an underlying condition such as:

- Reactive hypoglycemia: An exaggerated insulin response causing low blood sugar after meals.

- Insulin resistance or prediabetes: Cells become less responsive to insulin, leading to unstable glucose control.

- Postprandial hyperglycemia: Common in type 2 diabetes, where blood sugar rises too high after eating.

- Chronic fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia: Conditions where energy regulation is impaired, and meals may worsen symptoms.

- Gastrointestinal disorders: Conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or celiac disease can cause fatigue due to malabsorption or inflammation.

A healthcare provider can perform blood tests (e.g., fasting glucose, HbA1c, insulin levels) to assess metabolic health and rule out medical causes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it normal to feel sleepy after lunch?

Yes, mild drowsiness after lunch is common due to the body’s natural circadian rhythm, which dips in the early afternoon. However, excessive fatigue may indicate poor meal choices, overeating, or an underlying health issue.

Can artificial sweeteners cause tiredness after eating?

Some studies suggest that artificial sweeteners like aspartame or sucralose may disrupt gut bacteria and insulin signaling, potentially contributing to fatigue in sensitive individuals. While evidence is mixed, switching to natural sweeteners like stevia or monk fruit may help some people.

Does eating late at night cause worse fatigue?

Yes. Eating large meals close to bedtime forces your body to digest while preparing for sleep, which can interfere with rest quality and leave you feeling groggy the next morning. Aim to finish eating 2–3 hours before bed.

Final Thoughts: Take Control of Your Energy

Feeling tired after eating doesn’t have to be inevitable. While sugar crashes do happen, they’re just one piece of a larger puzzle that includes digestion, meal composition, hydration, and overall health. By paying attention to what, how much, and when you eat, you can dramatically improve your energy stability.

Start small: swap one refined carb for a fiber-rich alternative, add protein to your snacks, or take a short walk after dinner. Over time, these changes compound into lasting improvements in how you feel throughout the day.

“The best diet for energy isn’t about restriction—it’s about balance, timing, and listening to your body’s signals.” — Dr. Marcus Tran, Functional Medicine Practitioner

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?