Many people notice a clicking, popping, or cracking sound in their knees when they squat—sometimes repeatedly, sometimes only under certain conditions. While this can be alarming, especially if you're new to strength training or have recently increased your activity level, knee noise alone is not always a cause for concern. Joint sounds are surprisingly common and often benign. However, understanding the underlying causes, distinguishing between harmless crepitus and potentially problematic symptoms, and knowing when to take action can make a significant difference in long-term joint health.

This article explores the biomechanics of knee clicking during squatting, reviews the most frequent causes, and provides practical guidance on prevention, management, and when medical evaluation may be necessary.

The Science Behind Knee Clicking: What Causes the Sound?

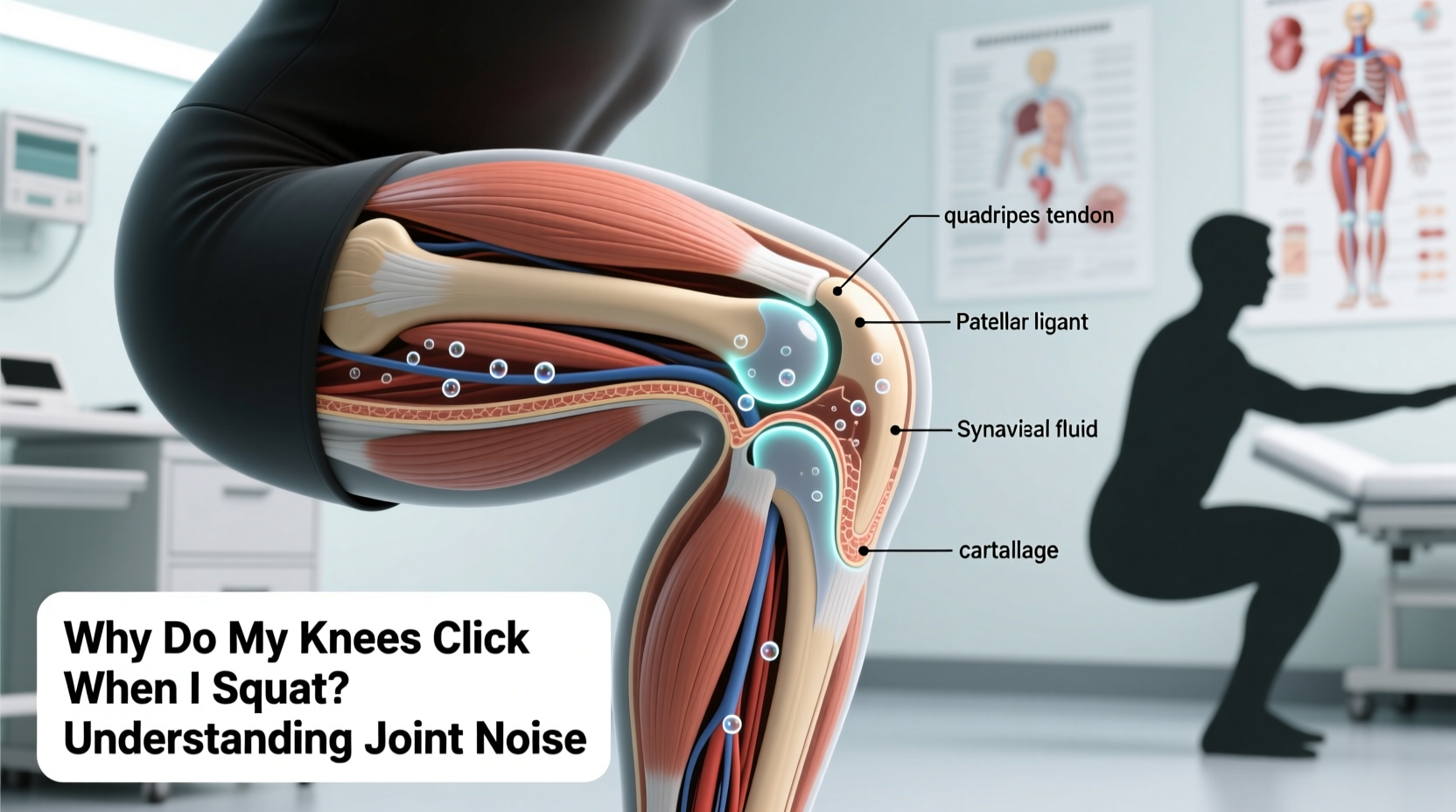

Knee joint noise—known medically as crepitus—can arise from several physiological processes. The most common sources include:

- Cavitation: When pressure changes rapidly within the synovial fluid of the joint (such as during a deep squat), small gas bubbles can form and collapse, producing a popping sound. This is similar to what happens when someone cracks their knuckles.

- Tendon or ligament movement: As tendons and ligaments shift over bony structures during motion, they can snap or flick, creating audible clicks. This is especially noticeable when the iliotibial band moves over the lateral femoral condyle.

- Cartilage irregularities: Over time, cartilage surfaces can develop minor imperfections. As the knee bends and straightens, these uneven areas may rub together, generating a grinding or grating sensation accompanied by sound.

- Patellar tracking issues: The kneecap (patella) glides along a groove in the femur. If alignment is slightly off due to muscle imbalances or anatomical variation, it may track unevenly, causing intermittent clicking.

Importantly, research shows that **asymptomatic knee crepitus**—joint noise without pain, swelling, or instability—is extremely common. A 2019 study published in *The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy* found that over 70% of asymptomatic individuals reported hearing knee noises during functional movements like squatting.

“Joint sounds are not inherently pathological. The presence of noise without pain or dysfunction does not indicate damage.” — Dr. Laura Mitchell, Sports Medicine Physician

When Is Knee Clicking Normal—and When Should You Be Concerned?

Not all knee noise is created equal. The key factor in determining whether clicking is harmless or a sign of an underlying issue lies in accompanying symptoms.

Here’s how to differentiate between benign and concerning knee sounds:

| Feature | Benign Clicking | Potentially Problematic |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | No pain present | Pain occurs with or after clicking |

| Swelling | Absent | Noticeable swelling or warmth |

| Frequency | Intermittent, situational | Consistent with every repetition |

| Instability | No buckling or giving way | Sensation of knee “giving out” |

| Range of Motion | Full, smooth movement | Stiffness or locking |

If clicking is isolated and doesn’t interfere with performance or comfort, it’s typically not a red flag. However, if it begins to coincide with discomfort, reduced mobility, or mechanical symptoms such as catching or locking, further assessment is warranted.

Common Causes of Symptomatic Knee Clicking During Squats

While occasional noise is normal, persistent or painful clicking may point to specific musculoskeletal conditions. Below are some of the most frequently diagnosed causes:

Plica Syndrome

The synovial plica are remnants of fetal tissue in the knee. In some individuals, these folds become irritated or thickened, especially with repetitive flexion like squatting. When the plica catches during movement, it can produce a snapping sensation and localized pain, usually on the inner side of the knee.

Meniscus Tears

The meniscus acts as a shock absorber between the femur and tibia. A tear—especially a bucket-handle type—can cause the knee to catch or lock during motion. Clicking may occur at a specific point in the range of motion, often around 30–60 degrees of flexion.

Chondromalacia Patellae

This condition involves softening or breakdown of the cartilage beneath the kneecap. It commonly affects individuals with poor patellar tracking or those who perform high-volume lower-body training. Pain worsens with prolonged sitting or descending stairs and may be accompanied by grinding sounds.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS)

Often called \"runner’s knee,\" PFPS results from overuse, muscle imbalances, or improper biomechanics. While not always associated with structural damage, it can lead to abnormal patellar movement and resultant clicking.

Osteoarthritis

In older adults or those with prior joint injury, degenerative changes in the joint surface can lead to roughened cartilage. Movement across these areas produces a gritty, grinding sound (crepitus) and is often associated with stiffness and swelling.

Step-by-Step Guide to Assessing and Managing Knee Clicking

If you’re experiencing knee noise during squats, follow this structured approach to determine whether intervention is needed:

- Monitor Symptoms Over Time: Keep a log for 2–3 weeks noting when the clicking occurs, whether it’s painful, and any triggers (e.g., depth of squat, fatigue).

- Assess Movement Quality: Record yourself squatting from the side and front. Look for signs of knee valgus (knees caving inward), excessive forward lean, or asymmetry.

- Test Range of Motion: Perform unloaded squats, lunges, and step-ups. Note any restriction, catching, or pain onset.

- Evaluate Muscle Balance: Check strength and activation in glutes, quadriceps (especially VMO), hamstrings, and hip abductors. Weakness in these areas can alter joint mechanics.

- Modify Training Temporarily: Reduce squat depth or load if pain is present. Substitute with box squats or split squats to decrease shear forces.

- Introduce Targeted Mobility Work: Focus on ankle dorsiflexion, hip internal rotation, and thoracic extension—common limitations that affect squat mechanics.

- Consult a Professional: If symptoms persist beyond 2–3 weeks despite modifications, seek evaluation from a physical therapist or sports medicine specialist.

Prevention and Long-Term Joint Health Strategies

Maintaining healthy knees isn’t just about avoiding pain—it’s about optimizing function and resilience. Incorporate these evidence-based practices into your routine:

Strengthen Supporting Musculature

Balanced strength in the hips, quads, and posterior chain reduces stress on the knee joint. Prioritize exercises like:

- Clamshells and side-lying leg lifts (glute medius activation)

- Bulgarian split squats (unilateral strength and stability)

- Terminal knee extensions with resistance bands (VMO targeting)

- Deadlifts and hip thrusts (posterior chain development)

Improve Movement Mechanics

Proper squat technique minimizes unnecessary strain. Key cues include:

- Initiate the movement by pushing hips back

- Keep knees aligned over toes (not collapsing inward)

- Maintain a neutral spine throughout

- Distribute weight evenly across the foot (avoid heel lift)

Warm Up Adequately

Cold joints are more prone to aberrant movement patterns. A dynamic warm-up increases blood flow, enhances neuromuscular control, and prepares connective tissues for loading. Include leg swings, walking lunges, bodyweight squats, and ankle circles before lifting.

Maintain a Healthy Body Weight

Every pound of body weight exerts up to 4 pounds of force on the knee during a squat. Even modest weight loss can significantly reduce joint stress and slow cartilage wear.

Nutrition and Recovery

Collagen synthesis, inflammation control, and tissue repair depend on proper nutrition. Ensure adequate intake of vitamin C, omega-3 fatty acids, protein, and antioxidants. Consider collagen supplementation (10–15g daily) taken with vitamin C 30–60 minutes before exercise to support connective tissue remodeling.

“Movement is medicine for the joint. Controlled loading stimulates cartilage health, while prolonged inactivity accelerates degeneration.” — Dr. Rajiv Mehta, Orthopedic Biomechanist

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it bad to crack your knees on purpose?

No, intentionally cracking your knees through stretching or manipulation is generally safe if done gently and without pain. The sound comes from gas release in the joint fluid and does not cause arthritis. However, aggressive or forceful manipulation should be avoided.

Can squatting damage your knees?

No—when performed with proper form and appropriate loading, squatting strengthens the muscles around the knee and improves joint stability. Research consistently shows that resistance training, including deep squats, does not increase osteoarthritis risk in healthy individuals.

Should I stop squatting if my knees click?

Only if the clicking is accompanied by pain, swelling, or mechanical symptoms like locking. If there’s no discomfort, continuing to squat with attention to form and progressive overload is beneficial. However, if uncertainty persists, consult a physical therapist for a personalized assessment.

Conclusion: Listen to Your Body, Not Just the Noise

Knee clicking during squats is far more common than most people realize—and in the vast majority of cases, it’s nothing to fear. The human body is designed to move, adapt, and withstand load. Joint sounds are often just a byproduct of complex biomechanics in action.

What matters most is how your knees feel, not just what they sound like. By focusing on movement quality, muscular balance, and gradual progression, you can maintain strong, resilient joints for years to come. Don’t let harmless noise deter you from building strength and mobility.

If pain, swelling, or dysfunction emerges, don’t ignore it. Early intervention can prevent minor issues from becoming chronic problems. Take ownership of your joint health with informed choices, consistent care, and professional guidance when needed.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?