Placing houseplants near a window seems like the most natural thing in the world. Sunlight streams in, leaves stretch toward the glass, and you assume everything is perfect. Yet, week after week, your peace lily droops, your pothos loses leaves, or your succulent turns mushy. You're not alone. Thousands of plant lovers make the same assumption: that any spot with sunlight is a good spot for plants. But the reality is more complex—and often counterintuitive.

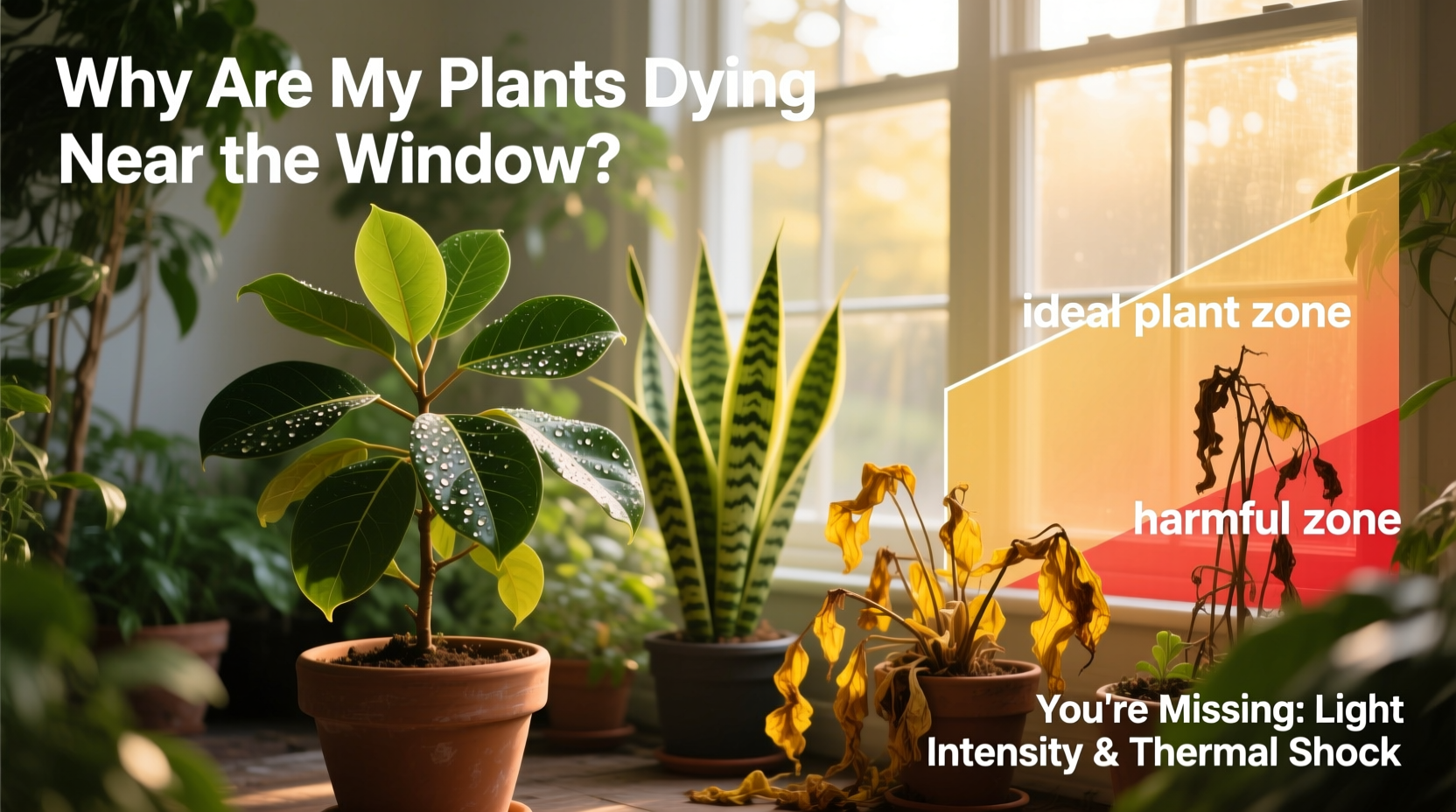

The space just inches from your window can be one of the most extreme microclimates in your home. Temperature swings, inconsistent humidity, and deceptive light patterns create conditions that mimic deserts or arctic zones—depending on the season. What looks like a sun-drenched paradise might actually be a slow death trap for many common indoor plants.

Understanding what’s really happening at your windowsill is the first step toward breaking the cycle of repeated plant loss. It's not just about light—it's about thermal dynamics, moisture gradients, and species-specific needs that are often overlooked.

The Illusion of Ideal Light

Natural light is essential, but not all sunlight is beneficial. Many assume that south-facing windows (in the Northern Hemisphere) are ideal year-round, but this exposure can scorch shade-loving plants like ferns or calatheas during summer afternoons. Conversely, north-facing windows may seem safe but often provide insufficient light for anything beyond low-light tolerant species such as ZZ plants or snake plants.

Light intensity changes dramatically based on time of day, season, and even weather. A window that delivers soft morning light in spring becomes a blazing spotlight by midsummer. Glass filters out some UV rays, but it doesn’t reduce heat or intensity enough to protect delicate foliage.

Additionally, reflective surfaces inside your home—like mirrors or white walls—can amplify light in unexpected ways, creating hotspots that stress plants. The key isn’t just placing a plant near a window, but matching the right plant to the specific quality and duration of light available.

Temperature Extremes: The Hidden Killer

Windows are weak points in insulation. During winter, cold air pools near the glass, especially at night. Even if your room feels warm, the temperature within 6 inches of the pane can drop significantly—sometimes below 50°F (10°C), which is dangerous for tropical species like philodendrons or crotons.

In contrast, summer brings the opposite problem: solar gain. Sunlight passing through glass heats up the air in a small zone near the window, creating a greenhouse effect. Temperatures can soar above 100°F (38°C) on sunny afternoons, cooking roots and causing leaf burn. This phenomenon is particularly severe with double-glazed or sealed windows that trap heat.

“Many plant deaths near windows aren’t due to poor care—they’re due to microclimate mismatch. A plant might thrive three feet away from the same window.” — Dr. Lena Reyes, Urban Horticulturist, Brooklyn Botanic Garden

Avoid placing sensitive plants directly against the glass. Instead, pull them back 6–12 inches to escape the most extreme temperature fluctuations. In older homes with single-pane windows, consider using insulated curtains at night to buffer cold drafts.

Humidity Collapse and Airflow Issues

Indoor humidity levels often drop near windows, especially when heating or cooling systems are running. As warm indoor air meets cold glass, condensation forms—and then evaporates—creating a localized dry zone. Plants like fittonia, maranta, or orchids that require consistent humidity suffer quickly in these conditions.

Meanwhile, stagnant air near sealed windows prevents proper transpiration and increases the risk of fungal diseases. Without gentle air movement, moisture accumulates on leaves overnight, inviting mold and mildew. On the flip side, drafty windows with constant airflow can dehydrate soil and foliage faster than you can water.

The solution lies in balancing moisture and circulation. Grouping humidity-loving plants together creates a shared microclimate. Placing a small pebble tray with water beneath the pot (without letting roots sit in water) can elevate local humidity. For airflow, a ceiling fan on low or periodic ventilation helps—but avoid direct blasts on delicate leaves.

Soil and Water Mismanagement in High-Stress Zones

Plants near windows often experience uneven watering patterns. Direct sun accelerates evaporation, leading owners to overwater in response. However, the root zone may still stay wet if the pot lacks drainage or the plant is in a decorative outer container. This combination—dry surface, soggy base—is a recipe for root rot.

Conversely, in winter, reduced light and lower temperatures slow down metabolism. Plants use less water, but owners may continue summer watering schedules, again promoting rot. The proximity to cold glass can also chill the pot, further slowing drying and increasing disease risk.

| Season | Common Issue | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Summer | Overheating, rapid drying, leaf scorch | Move slightly back from window, increase humidity, check soil daily |

| Winter | Cold drafts, under-watering, dormancy confusion | Lift pots off cold sills, reduce watering, insulate with bubble wrap |

| Spring/Fall | Rapid temperature shifts, inconsistent light | Monitor daily, adjust placement weekly, acclimate slowly |

Mini Case Study: The Failing Fiddle Leaf Fig

Sarah placed her fiddle leaf fig in a bright southwest-facing window, believing she was giving it perfect conditions. Within two months, the edges of the leaves turned brown, new growth stalled, and lower leaves dropped. She watered weekly, misted daily, and wiped the leaves regularly—yet the plant declined.

Upon inspection, a few issues became clear: the pot sat directly on a cold marble windowsill in winter, chilling the roots; afternoon sun scorched the leaves; and despite misting, the air near the glass remained extremely dry due to HVAC airflow. After moving the plant 18 inches back from the window, adding a humidifier nearby, and switching to a moisture meter for watering, the plant stabilized within six weeks and began producing healthy new leaves.

Choosing the Right Plant for Your Window Type

Not all windows are equal—and not all plants belong at them. Matching species to exposure is critical. Here’s a guide to help align your choices:

- South-facing (Northern Hemisphere): Best for sun-lovers: cacti, succulents, citrus, hibiscus. Use sheer curtains in summer to diffuse intense midday light.

- East-facing: Ideal for moderate light plants: pothos, spider plants, African violets. Morning sun is gentle and promotes steady growth.

- West-facing: Strong afternoon sun. Suitable for jade plants, aloe, or herbs like rosemary. Can be too harsh for ferns or peace lilies without filtering.

- North-facing: Low light only. Stick to snake plants, ZZ plants, or Chinese evergreens. Avoid flowering or fruiting species.

Step-by-Step Guide to Reviving Window-Edge Plant Health

- Assess the microclimate: Measure temperature and humidity near the window at different times of day using a digital hygrometer.

- Pull plants back: Move them 6–24 inches from the glass to avoid extremes.

- Check for drafts: Feel for cold air leaks around the window frame, especially at night.

- Evaluate light quality: Note when direct sun hits the plant and for how long. Adjust with blinds or relocation.

- Inspect soil and roots: If a plant is struggling, gently remove it from the pot to check for root rot or compaction.

- Adjust watering: Let the top inch of soil dry before watering, and always ensure drainage.

- Rotate regularly: Turn the pot a quarter turn weekly to promote symmetrical growth.

- Monitor progress: Take weekly photos to track improvement or decline.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I leave my plants on the windowsill if I have double-glazed windows?

Double-glazing reduces heat loss but can increase heat buildup in summer. While it buffers cold in winter, the sealed environment may trap excessive warmth and humidity, raising the risk of pests and rot. Monitor temperature closely and avoid direct contact between pots and glass.

Why do the tips of my plant’s leaves turn brown near the window?

Brown tips are often caused by low humidity, inconsistent watering, or salt buildup from tap water. Near windows, dry air from HVAC systems intensifies moisture loss. Try using filtered or rainwater and increase ambient humidity with a tray or humidifier.

Should I fertilize plants near windows more often since they get more light?

Only during active growing seasons (spring and summer). More light means higher metabolic activity, so monthly feeding with a balanced liquid fertilizer can help. However, never fertilize in winter when growth slows, regardless of light levels.

Final Checklist: Is Your Window Safe for Plants?

- ✅ Temperature stays above 60°F (15°C) at night

- ✅ No direct contact between pot and cold/hot glass

- ✅ Humidity is above 40% for tropical species

- ✅ Soil dries appropriately between waterings

- ✅ Light matches the plant’s natural preferences

- ✅ There’s gentle air circulation without strong drafts

- ✅ Pots have drainage holes and aren’t sitting in water

Conclusion: Rethink the Windowsill

The windowsill isn’t a default “plant zone”—it’s a high-risk environment that demands thoughtful management. By recognizing the invisible forces at play—temperature spikes, humidity drops, and deceptive light—you can transform a death trap into a thriving display. Success isn’t about watering more or buying hardier plants; it’s about understanding the ecosystem you’ve created.

Start observing your space like a botanist: track changes, test conditions, and match each plant to its true needs. With small adjustments, your window can become a vibrant showcase of green life instead of a graveyard of wilted stems.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?