Solids are all around us—tables, books, metals, ice cubes. One of their most defining characteristics is that they maintain a fixed shape without needing a container. Unlike liquids or gases, which flow and conform to their surroundings, solids hold their form. But what causes this behavior at the molecular level? The answer lies in the arrangement and interaction of particles within the solid state. Understanding why solids have a definite shape requires exploring atomic structure, bonding forces, and energy dynamics that distinguish solids from other states of matter.

The Role of Particle Arrangement in Solids

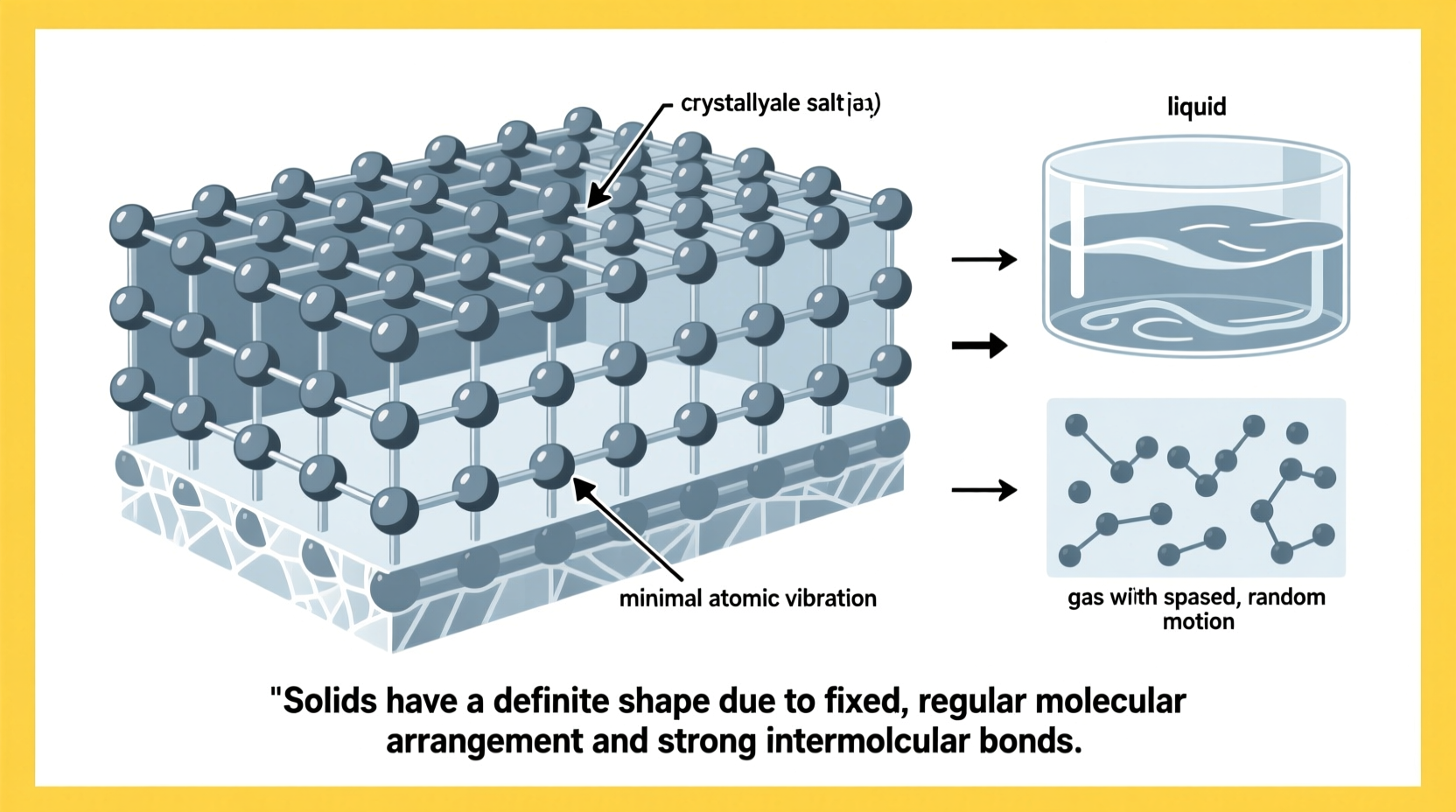

In any material, the physical properties stem directly from how its constituent particles—atoms, molecules, or ions—are arranged and how they move. In solids, these particles are tightly packed in a highly ordered structure. This organization is often crystalline, meaning the particles repeat in a precise three-dimensional lattice. Even in amorphous solids like glass, where long-range order is absent, particles remain locked in place with limited freedom of movement.

This rigidity arises because the particles in a solid vibrate in fixed positions but do not move freely past one another. Their kinetic energy is low compared to their potential energy, which is dominated by strong intermolecular forces. As a result, the overall structure remains stable and maintains its shape under normal conditions.

Intermolecular Forces and Bonding Strength

The strength of the forces between particles determines whether a substance exists as a solid, liquid, or gas at a given temperature. In solids, these intermolecular attractions—such as ionic bonds, covalent networks, metallic bonds, or strong van der Waals forces—are powerful enough to overcome the thermal motion of the particles.

For example:

- Ionic solids like sodium chloride (table salt) consist of positively and negatively charged ions held together by electrostatic forces in a rigid crystal lattice.

- Covalent network solids such as diamond or quartz feature atoms linked by a continuous network of covalent bonds, creating an extremely hard and stable structure.

- Metallic solids like iron or copper maintain shape due to a \"sea\" of delocalized electrons binding positive metal ions in a fixed array.

- Molecular solids like ice or sugar rely on hydrogen bonding or dipole-dipole interactions, which, while weaker than ionic or covalent bonds, are sufficient to lock molecules into place at low temperatures.

“Solids resist deformation because their particles are locked in position by a balance of attractive and repulsive forces.” — Dr. Alan Reyes, Materials Scientist

Comparison of States of Matter

| Property | Solid | Liquid | Gas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shape | Definite | Indefinite (takes container) | Indefinite (fills container) |

| Volume | Definite | Definite | Indefinite |

| Particle Arrangement | Ordered, tightly packed | Close but disordered | Random, far apart |

| Particle Motion | Vibration only | Slide past each other | Free, rapid movement |

| Compressibility | Very low | Low | High |

This comparison highlights why solids uniquely possess a definite shape: their internal structure resists external changes unless significant energy is applied.

Real-World Example: Ice Melting into Water

Consider a simple scenario: an ice cube sitting on a plate at room temperature. Initially, it holds a clear, defined cubic shape. Over time, it begins to melt, turning into liquid water that spreads across the surface.

At the molecular level, the water molecules in ice are arranged in a hexagonal lattice, stabilized by hydrogen bonds. Each molecule is bonded to four others, forming a rigid structure. As heat from the environment transfers to the ice, the molecules gain kinetic energy. Eventually, this energy overcomes the hydrogen bonds holding them in place. The lattice breaks down, allowing molecules to slide past one another—transitioning from solid to liquid.

This phase change demonstrates that a solid’s definite shape depends on environmental conditions, particularly temperature. Remove enough thermal energy, and even gases like carbon dioxide can become solid (dry ice). Add energy, and most solids will eventually lose their shape through melting.

Do’s and Don’ts When Observing Solid Behavior

| Do’s | Don’ts |

|---|---|

| Observe how temperature affects solid integrity (e.g., chocolate softening in heat) | Assume all solids are equally rigid—some, like wax, deform easily under pressure |

| Use models or diagrams to visualize crystal lattices | Ignore exceptions like amorphous solids that lack regular structure |

| Compare everyday materials (metal vs. plastic) to understand bonding differences | Treat melting point as the only indicator of structural stability |

Step-by-Step: How Heat Affects a Solid’s Shape

- Initial State: The solid’s particles vibrate in fixed positions within a stable lattice.

- Heat Application: Thermal energy is absorbed, increasing particle vibration.

- Energy Threshold: At the melting point, vibrational energy exceeds the binding forces.

- Lattice Breakdown: The ordered structure collapses; particles begin to move independently.

- Phase Change: The substance transitions to a liquid, losing its definite shape.

This process is reversible. Removing heat allows intermolecular forces to re-establish order, leading to freezing and the restoration of a definite shape.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a solid ever lose its shape without melting?

Yes. Some solids undergo plastic deformation under stress. For example, bending a metal paperclip changes its shape permanently without melting. This occurs when layers of atoms slide past each other under force, breaking and reforming bonds in new positions.

Why doesn’t a sponge have a perfectly definite shape?

A sponge may seem to lack a fixed shape because it’s compressible and flexible, but it’s still a solid. Its macroscopic softness comes from its porous structure and elastic material composition, not from fluid-like particle movement. At the molecular level, its polymer chains remain bonded in place.

Are all crystals solids?

Yes, all crystals are solids, but not all solids are crystals. Crystalline solids have a repeating atomic pattern (like salt or diamonds), while amorphous solids (like rubber or glass) lack long-range order but still maintain rigidity due to restricted molecular motion.

Practical Tips for Teaching or Learning This Concept

- Encourage learners to classify household items based on shape retention.

- Demonstrate phase changes using safe materials like butter or chocolate.

- Highlight exceptions like gels or colloids that blur the line between solid and liquid.

- Use animations or simulations to show particle motion in different states.

- Relate the concept to engineering—why bridges use steel (strong metallic bonding) instead of softer materials.

Conclusion: The Stability of Structure Defines Solidity

The definite shape of a solid is not just an observable trait—it’s a direct consequence of physics and chemistry working in harmony. From the strength of chemical bonds to the minimal kinetic energy of particles, every factor contributes to structural integrity. Whether it’s a diamond enduring immense pressure or an ice cube maintaining form in the freezer, the principle remains the same: solids hold their shape because their particles are bound in place.

Understanding this concept opens doors to deeper insights in material science, engineering, and everyday decision-making—from choosing cookware to preserving food. The next time you pick up a book or walk across a wooden floor, remember the invisible lattice of atoms working silently to keep everything firmly in place.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?