Every holiday season, thousands of homeowners report a puzzling issue: their garage door opener stops responding reliably—or fails entirely—only when the outdoor Christmas lights are turned on. The remote won’t trigger the door, the wall button becomes sluggish, or the opener emits erratic beeps before refusing to act. This isn’t coincidence or aging hardware—it’s radio frequency (RF) interference, a well-documented but widely misunderstood phenomenon rooted in overlapping wireless spectrum use, electromagnetic design compromises, and decades-old regulatory allowances.

The problem lies not in faulty equipment per se, but in how modern LED light controllers—especially low-cost, non-certified models—generate and leak electromagnetic noise. Unlike traditional incandescent strings, many programmable LED controllers use switching power supplies and microcontroller-based pulse-width modulation (PWM) circuits that unintentionally broadcast broadband RF energy. When that energy overlaps with the 300–400 MHz band used by most residential garage door openers (particularly legacy units operating at 315 MHz or 390 MHz), it drowns out legitimate signals like static drowning out a radio station.

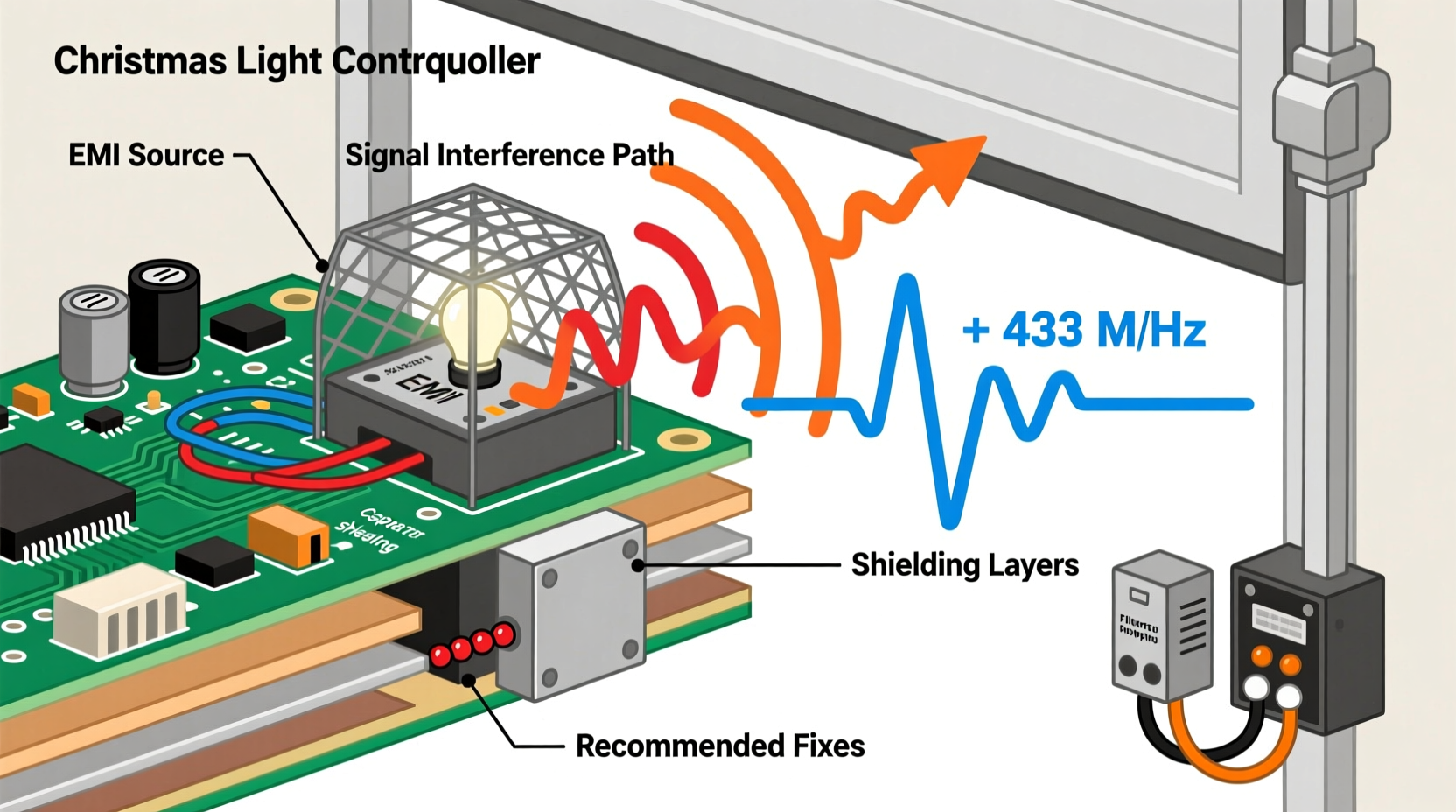

How RF Interference Actually Works Between Light Controllers and Garage Openers

Garage door openers rely on narrowband RF communication. Your remote transmits a coded signal—typically 315 MHz for older systems or 390 MHz for newer ones—using amplitude shift keying (ASK) or frequency shift keying (FSK). The receiver in the opener’s motor unit listens for that precise frequency and modulation pattern. It expects clean, low-noise reception.

In contrast, many budget LED light controllers—especially those sold online without FCC ID markings—use unshielded switch-mode power supplies (SMPS) and poorly filtered microcontrollers. These components generate high-frequency harmonics as they rapidly cycle current to dim or animate LEDs. A typical SMPS operating at 20–100 kHz can produce harmonics extending well into the VHF band (30–300 MHz) and beyond. The third, fifth, or seventh harmonic of a 45 kHz oscillator, for example, lands directly at 315 kHz, 495 kHz, and 675 kHz—but more critically, its *broadband noise floor* raises across adjacent bands, including the critical 315 MHz opener band.

This isn’t intentional transmission. It’s electromagnetic leakage—like an untuned radio transmitter bleeding noise into neighboring frequencies. The garage opener’s receiver, designed for sensitivity rather than selectivity, picks up this noise as false “signal activity,” causing desensitization (blocking) or misinterpretation of command codes.

Why Some Controllers Cause Problems—and Others Don’t

Not all controllers behave the same way. Interference potential depends heavily on three engineering factors: shielding integrity, filtering quality, and regulatory compliance.

| Factor | Low-Risk Controller | High-Risk Controller |

|---|---|---|

| FCC Certification | Bears visible FCC ID; tested to Part 15B limits for unintentional radiators | No FCC ID; sold as “for indoor use only” or lacks certification documentation |

| Power Supply Design | Uses linear or well-filtered SMPS with common-mode chokes and Y-capacitors | Uses bare-bones SMPS with no EMI filtering—often just a single diode bridge and capacitor |

| Enclosure & Shielding | Die-cast aluminum or metalized plastic housing; internal copper tape or ferrite coatings | Thin ABS plastic housing; no internal shielding; exposed PCB traces near case seams |

| Wiring Practice | Twisted-pair or shielded control wiring; ferrite clamps on output leads | Untwisted, parallel-conductor wiring acting as unintentional antennas |

Manufacturers targeting cost-sensitive markets often omit these features. A controller priced under $25 is statistically far more likely to exceed FCC radiated emission limits by 10–20 dB than one retailing above $60—enough to push noise from “barely detectable” to “receiver-blinding.”

A Real-World Case Study: The Suburban Garage That Wouldn’t Open

In December 2022, Sarah M., a homeowner in Overland Park, KS, installed a set of 200-node RGB LED net lights controlled by a $19 Wi-Fi-enabled hub. Within two days, her Chamberlain WhisperDrive opener—installed in 2018 and operating at 315 MHz—began failing intermittently. The wall button worked fine, but remotes had <5% success rate when lights were active. She replaced batteries, reprogrammed remotes, and even reset the opener’s logic board—nothing helped.

An electrician measured RF noise using a handheld spectrum analyzer and found a 28 dBµV/m spike centered at 315.2 MHz—exactly matching the opener’s receive frequency—whenever the light controller cycled through its “twinkle” effect. The source? A poorly filtered 42 kHz PWM driver stage inside the controller’s plastic housing. The electrician applied two ferrite clamp-on cores (Fair-Rite 2643002402) around the controller’s DC output cable near the connector, then added a second pair where the cable entered the outdoor junction box. Signal reliability returned to 100%. Total fix time: 17 minutes. Cost: $8.95.

Step-by-Step Shielding Protocol: From Diagnosis to Resolution

- Confirm the interference link: Turn off all Christmas lights. Test garage door operation with remotes and wall button for 5 minutes. Then turn lights on—preferably on a dynamic mode (chase, fade, twinkle)—and retest. If failure correlates precisely with lights-on, interference is confirmed.

- Isolate the culprit controller: If using multiple controllers, power them down one at a time while testing. Most interference originates from the *first* or *largest* controller in the chain—not necessarily the closest to the garage.

- Apply ferrite suppression: Use two-turn, high-permeability ferrite cores rated for 1–300 MHz (e.g., Fair-Rite 31 or 43 material). Clamp one core around the DC power cable *within 2 inches* of the controller’s output terminal. Add a second core within 2 inches of where the cable enters any enclosure or conduit. For AC-powered controllers, apply cores to both line and neutral conductors together (never separately).

- Improve grounding and separation: Ensure the light controller has a proper ground connection if AC-powered. Relocate the controller at least 10 feet horizontally—and ideally 6 feet vertically—away from the garage door opener’s antenna (usually a thin wire protruding from the motor head). Avoid routing light cables parallel to the opener’s antenna wire.

- Upgrade or replace selectively: If ferrites yield only partial improvement, replace the offending controller with an FCC-ID-verified model (look for IDs beginning with “2AHRZ” or “2AJ4N”). Prioritize units listing “EMI/RFI filtered” in specifications. For permanent installations, consider hardwiring with shielded twisted-pair cable (e.g., Belden 8761) and terminating shields to grounded metal junction boxes.

Expert Insight: What Engineers See in the Lab

“Interference isn’t about ‘bad’ controllers—it’s about trade-offs made in mass production. Every decibel of EMI filtering adds $0.37 to BOM cost. When you’re shipping 500,000 units, that’s $185,000 in margin erosion. So manufacturers cut corners—until consumers start calling service desks in December.” — Dr. Lena Torres, RF Compliance Engineer, Intertek EMC Lab, Chicago

“The most effective fix isn’t always the most expensive. A properly applied $2 ferrite core can attenuate noise by 20 dB at 315 MHz—equivalent to moving the controller 10x farther away. But it only works if placed correctly: within 5 cm of the noise source, on *both* conductors, with tight coupling.” — Mark Rhee, Senior Applications Engineer, Würth Elektronik eiSos

Prevention Checklist: Before You Hang a Single Bulb

- ✅ Verify FCC ID is printed on packaging and matches a live entry in the FCC ID Search database

- ✅ Choose controllers labeled “FCC Class B” (intended for residential use) over “Class A” (industrial)

- ✅ Avoid controllers with exposed circuit boards or ventilation slots near ICs or power components

- ✅ Prefer units with metal enclosures—even if painted—over all-plastic designs

- ✅ Install controllers indoors (garage, shed, covered porch) rather than exposed outdoors when possible

- ✅ Use dedicated 15-amp circuits for lighting—avoid sharing with garage door openers or refrigerators

FAQ

Can I shield my garage door opener instead of the light controller?

Technically yes—but it’s impractical and rarely effective. Opener receivers are designed for maximum sensitivity, not rejection. Adding shielding to the motor head risks blocking legitimate signals or overheating electronics. Ferriting the opener’s antenna wire may help slightly, but addressing the noise *at the source* (the controller) yields 5–10x better results with zero risk to opener function.

Will upgrading to a newer garage door opener solve this?

Modern openers (2020+) often use rolling-code encryption and operate at 390 MHz or 433 MHz—frequencies less commonly polluted by light controller harmonics. However, many still include 315 MHz fallback for compatibility with older remotes. If your new opener supports *exclusive* 390 MHz operation and you replace all remotes, interference likelihood drops significantly—but never to zero, as broadband noise spans multiple bands.

Do smart home hubs (like Alexa or Google Home) make interference worse?

Not inherently—but many low-cost smart plugs and hubs controlling lights use the same poorly filtered power supplies as standalone controllers. If your “smart” Christmas lights run through a $12 Wi-Fi plug, that plug—not the lights themselves—may be the real emitter. Always test individual components, not just lighting groups.

Conclusion

RF interference between Christmas light controllers and garage door openers isn’t magic—it’s physics, economics, and engineering choices converging in your driveway every December. The good news? You don’t need an electrical engineering degree or a $5,000 spectrum analyzer to resolve it. With systematic diagnosis, targeted ferrite suppression, and smarter purchasing habits, you can restore full, reliable operation to your garage door—without sacrificing festive ambiance.

This isn’t just about convenience. Unresolved interference can mask real safety issues—like a failing opener safety sensor or binding track—because symptoms mimic electronic failure. Taking 20 minutes to audit your light controllers this season protects both functionality and peace of mind.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?