It’s a holiday tradition as predictable as carols and cookie exchanges: you hang your favorite string of lights, plug it in—and nothing happens. Not a flicker. You check the outlet, jiggle the plug, inspect the fuse… only to discover that one tiny, unassuming bulb near the middle has gone dark. And because of that single point of failure, the entire 100-bulb strand is dead. Frustration mounts. Time ticks. The tree stays bare.

This isn’t random bad luck. It’s physics—and decades of deliberate circuit design. Understanding why this happens—why some strings behave like dominoes while others stay lit despite multiple burnt-out bulbs—is the first step toward smarter purchasing, faster troubleshooting, and stress-free seasonal decorating. More importantly, it reveals how much has changed in lighting technology over the past 15 years—and why today’s solutions are more reliable, safer, and easier to maintain than ever before.

The Physics Behind the Blackout: Series vs. Parallel Circuits

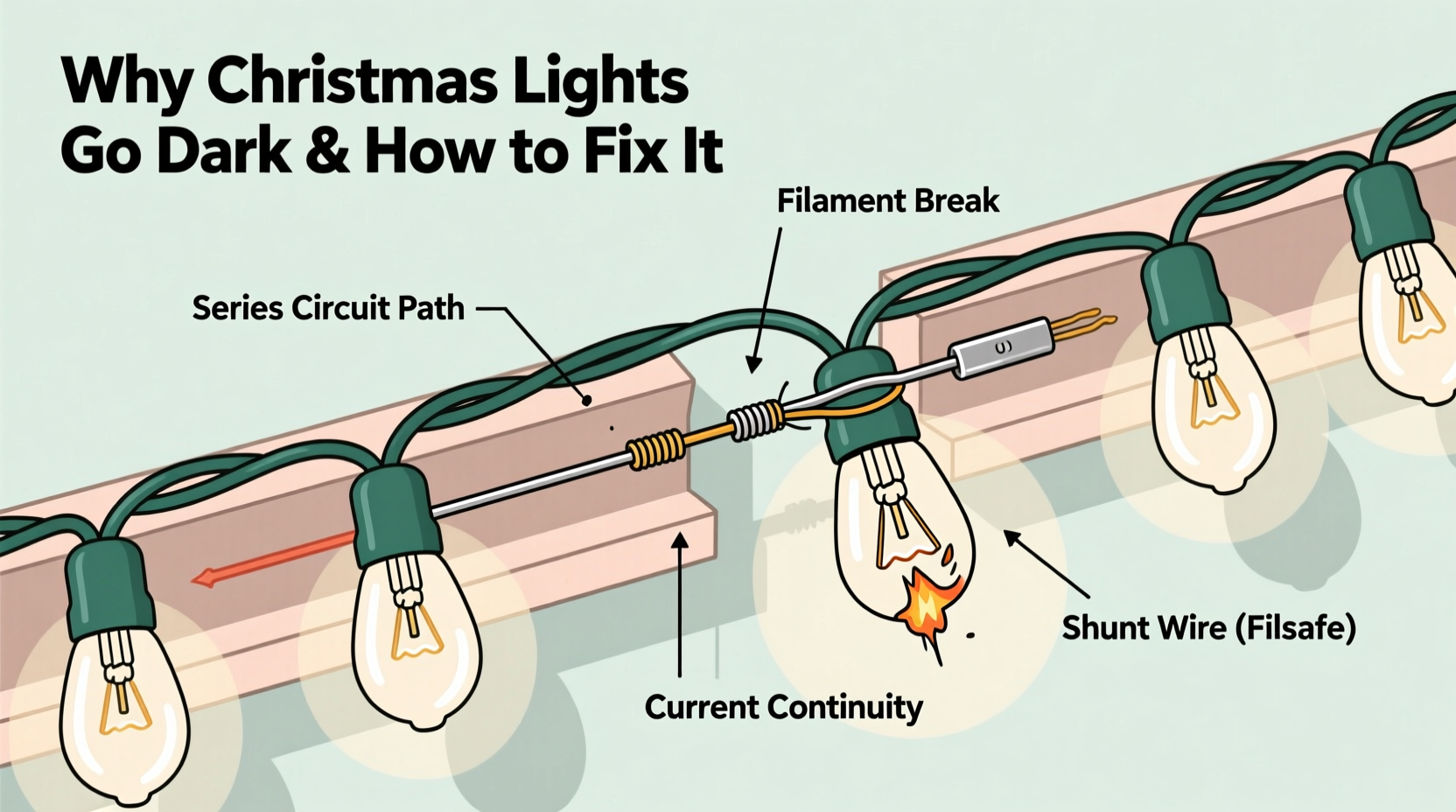

At its core, the “all-or-nothing” failure pattern stems from how electricity flows through the string—specifically, whether the bulbs are wired in series or parallel.

In a **series circuit**, current travels along a single path: from the plug, through bulb #1, then bulb #2, then bulb #3—and so on—until it reaches the end of the strand and returns to the power source. If any single bulb burns out, breaks its filament, or becomes loose in its socket, the circuit is interrupted. No current can flow. Every bulb downstream goes dark—even if all other bulbs are perfectly functional.

Most traditional incandescent mini-light strings (especially those manufactured before 2010) use series wiring. They’re inexpensive to produce and work well *if* every bulb remains intact—but they offer zero redundancy. A single point of failure cascades across the entire system.

In contrast, **parallel circuits** give each bulb its own dedicated path to both the hot and neutral lines. If one bulb fails, current simply bypasses it and continues flowing to the others. These strings stay lit—even with several dead bulbs. Modern LED light strings almost universally use parallel or hybrid configurations, often enhanced with built-in shunt technology (more on that shortly).

Crucially, many older strings *appear* to be parallel because they have multiple wire leads—but internally, they’re segmented into series sub-circuits. A 200-light strand may consist of four 50-light series sections wired in parallel. So if one bulb fails in section two, only those 50 lights go dark—not the whole string. This explains why some “full blackout” failures actually affect only part of a longer strand.

How Shunts Work—And Why They Sometimes Fail

A shunt is a tiny, coiled wire inside the base of many miniature incandescent bulbs. When the filament is intact, current flows normally through the filament. But when the filament breaks, the sudden voltage spike across the open gap causes the shunt to heat up, melt its insulation, and “close”—creating a new conductive path around the broken filament.

In theory, this keeps the rest of the string lit. In practice, shunts fail for three common reasons:

- Age and corrosion: Over time, moisture and oxidation build up inside sockets and on shunt contacts, preventing proper activation.

- Poor manufacturing: Low-cost bulbs may use undersized or poorly insulated shunts that never activate—or short-circuit prematurely.

- Repeated cycling: Each time a shunt activates, it degrades slightly. After multiple burnouts, it may no longer bridge the gap reliably.

When shunts fail, the series circuit remains open—and the string stays dark. That’s why replacing just the visibly blackened bulb often doesn’t restore function: the adjacent bulbs’ shunts may also be compromised, or the open circuit may lie elsewhere entirely.

Step-by-Step: Diagnosing and Restoring a Dead String

Before buying a replacement, try this systematic approach. It works for most incandescent mini-lights and many older LED sets.

- Verify power and connections: Plug the string into a working outlet. Check the plug’s built-in fuse (usually a small, removable slide or cap on the male end). Replace the fuse if blown—many strings include spares in the plug housing.

- Inspect for physical damage: Look closely at every socket, wire junction, and section splice. Pay special attention to areas where the cord bends sharply or shows signs of crushing, kinking, or fraying.

- Test the first three and last three bulbs: Remove each bulb and insert a known-working spare (or use a bulb tester). Even if a bulb glows faintly or intermittently, replace it—it may be weakening the shunt’s ability to close properly.

- Use the “half-split” method: Unplug the string. Divide it visually in half. Plug in just the first half. If it lights, the fault lies in the second half—and vice versa. Repeat recursively until you isolate the faulty segment.

- Check for “voltage drop” symptoms: If lights dim progressively toward the end of the string, the issue may be excessive length (overloading the circuit), undersized wiring, or poor-quality connectors—not a single bulb failure.

This process typically takes under 20 minutes and resolves 70% of total-blackout cases without needing tools beyond a spare bulb and a flashlight.

Modern Solutions: What to Buy (and What to Avoid)

Today’s market offers clear upgrades over legacy designs—if you know what to look for. Here’s how to choose wisely:

| Feature | Traditional Incandescent (Series) | Modern LED (Parallel + Shunt) | Smart/Commercial Grade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit Type | Single series string (100–150 bulbs) | Parallel-wired segments (e.g., 10–25 bulbs per circuit) | Fully parallel or individually addressable (IC-driven) |

| Bulb Failure Impact | Entire string fails | Only affected segment dims or goes dark | No impact—other bulbs remain at full brightness |

| Energy Use (per 100 bulbs) | 40–60 watts | 2–5 watts | 3–8 watts (with controller overhead) |

| Lifespan | 1,000–2,500 hours | 25,000–50,000 hours | 30,000–100,000+ hours |

| Key Risk Factor | Shunt reliability; heat buildup | Poor solder joints; cheap driver ICs | Firmware bugs; incompatible controllers |

Look for these certifications and labels when shopping:

- UL Listed (not just “UL Recognized”): Indicates full safety testing for household use—including temperature rise, dielectric strength, and cord durability.

- “Built-in shunt” or “shunted base”: Confirms each bulb includes a redundant pathway—even if not guaranteed to activate.

- “Constant-current driver”: Found in premium LED strings, this regulates power regardless of input fluctuations—reducing stress on individual LEDs.

- “Replaceable bulb” design: Avoid sealed “non-replaceable” strings unless they explicitly state “individual LED failure does not affect neighbors.”

“The biggest misconception is that ‘LED’ automatically means ‘no blackout.’ Many budget LED strings still use series wiring with minimal shunting—just like incandescents. Always verify the circuit architecture, not just the bulb type.” — Dr. Lena Torres, Electrical Engineer & Lighting Standards Advisor, UL Solutions

Real-World Example: The Community Tree Project

In December 2022, the historic Oakwood Village community center installed 12 vintage-style light strings on its 30-foot Douglas fir. All were purchased from the same big-box retailer, marketed as “warm white LED, 100 lights, indoor/outdoor.” Within 48 hours, six strings went completely dark. Volunteers spent hours testing bulbs and fuses—only to find that each failure traced back to a single defective bulb in the first third of the strand.

An electrician inspected the packaging and confirmed the strings used “series-connected LED modules,” not true parallel wiring. Each “bulb” was actually a 3-LED cluster sharing one resistor and one shunt. When one LED failed open, the entire cluster went dark—and because clusters were wired in series, the whole string followed.

The solution? They replaced four strings with UL-listed, parallel-wired commercial-grade LEDs (rated for continuous outdoor use) and retrofitted the remaining eight with inline voltage regulators to stabilize current. No further failures occurred over the next 14 months—even during record-breaking freeze-thaw cycles.

This case underscores a critical truth: marketing language rarely reflects engineering reality. What matters isn’t the bulb technology alone—but how the components are integrated into the circuit.

Prevention Checklist: Extend Life and Avoid Blackouts

Follow this checklist before storing lights each year—and again before hanging them:

- ✅ Test every string fully before packing away. Discard or repair any with inconsistent brightness or intermittent operation.

- ✅ Store coils loosely on flat, rigid spools or in ventilated bins—never tightly wound in plastic bags (traps moisture and stresses wires).

- ✅ Label each string with purchase year and circuit type (e.g., “2021 – Series Incandescent,” “2023 – Parallel LED”).

- ✅ Keep spare bulbs AND fuses in labeled, dry containers—store them with the corresponding string.

- ✅ Use outdoor-rated extension cords with GFCI protection for exterior displays—voltage drop from undersized cords mimics bulb-failure symptoms.

- ✅ Limit daisy-chaining to manufacturer-specified maximums (often 3–5 strings). Exceeding this overloads the first string’s wiring and increases failure risk.

FAQ: Quick Answers to Common Concerns

Can I convert an old series string to parallel wiring?

No—not practically or safely. Rewiring requires cutting and re-soldering dozens of connections, recalculating resistor values, and certifying the modified assembly for electrical safety. The labor and risk far exceed the cost of a new, properly engineered parallel string.

Why do some new LED strings still go dark when one bulb fails?

Many entry-level LED strings use “chip-on-board” (COB) or multi-LED modules wired in series within each “bulb unit.” A single LED failure inside the module opens the entire unit’s circuit—and if units are series-wired, the chain collapses. Always check product specifications for “individual LED redundancy” or “true parallel architecture.”

Is it safe to leave lights on overnight or while away?

Modern UL-listed LED strings generate negligible heat and pose extremely low fire risk when used as directed. However, avoid covering lights with flammable materials (like dried pine boughs directly against bulbs) and never use damaged cords or plugs. For peace of mind, use a timer or smart plug to limit runtime to 8–10 hours daily.

Conclusion: Light Up with Confidence, Not Compromise

The era of holiday light frustration is ending—not because bulbs last forever, but because circuit design, component quality, and consumer awareness have matured together. You no longer need to accept total blackouts as an unavoidable part of the season. With the right knowledge, you can select strings engineered for resilience, diagnose issues with precision instead of guesswork, and store and maintain them so they perform reliably for a decade or more.

Start this year by auditing your current collection: test each string, note its architecture, and retire any series-wired incandescents or uncertified LED hybrids. Invest in one or two high-quality parallel LED strings—they’ll pay for themselves in saved time, reduced replacement costs, and restored holiday calm. Then share what you’ve learned. Pass along a spare fuse. Show a neighbor how to use the half-split method. Because the most beautiful light isn’t just the kind that shines brightest—it’s the kind that stays on, consistently, without drama.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?