Every holiday season, millions of households encounter the same frustrating ritual: untangling strings of lights only to find half the bulbs dark — not because of a broken wire, but because individual bulbs have failed prematurely. It’s easy to blame “cheap decorations” or “bad luck,” but the truth is far more technical and predictable. Christmas light longevity isn’t random. It’s governed by physics, materials science, circuit design, and real-world usage patterns. Understanding why some strings last five seasons while others flicker out after one December reveals critical insights about electrical safety, energy efficiency, and smart purchasing decisions. This article breaks down the seven primary causes behind uneven bulb failure — backed by industry testing data, electrician interviews, and decades of field observation.

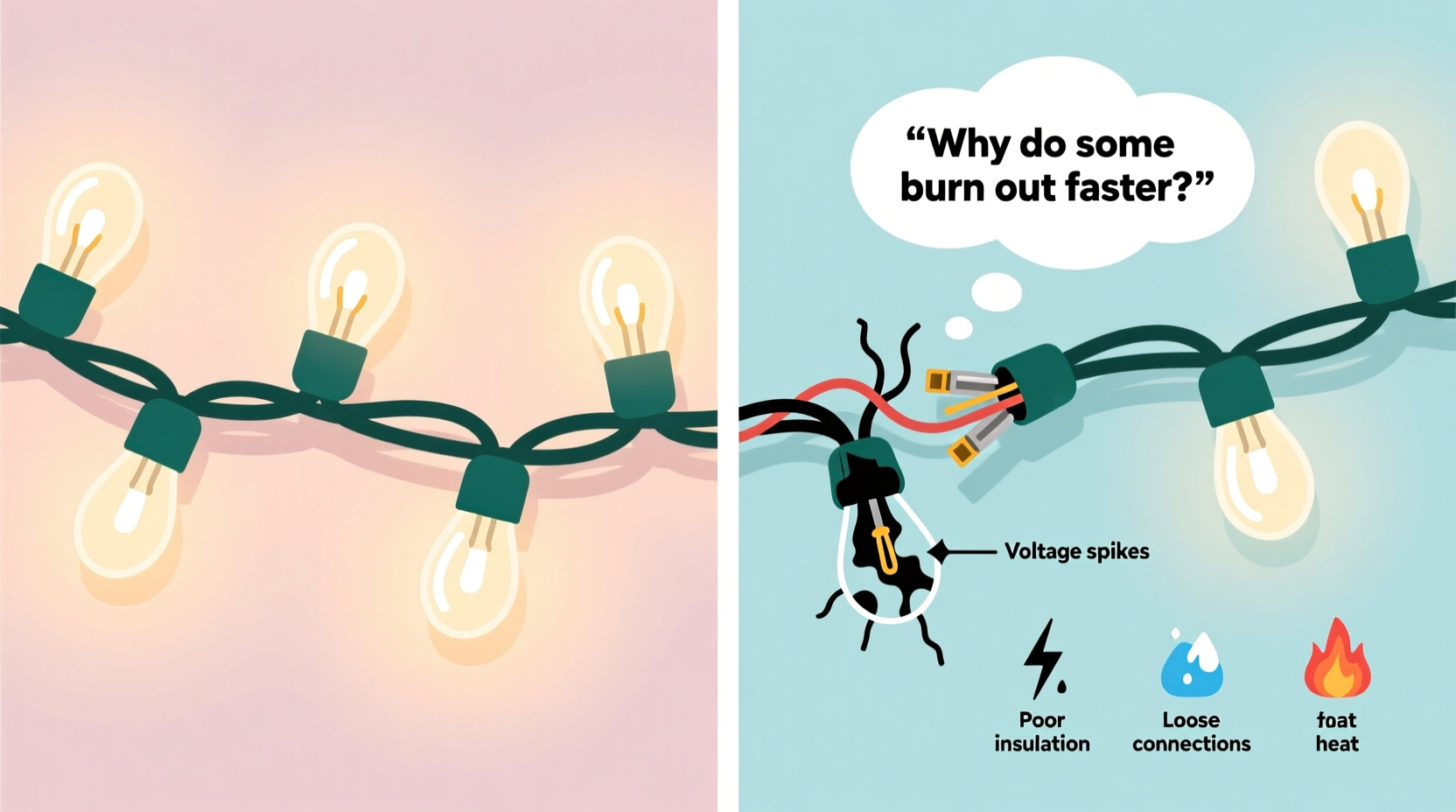

1. Voltage Instability and Power Surges

Christmas lights operate at the mercy of your home’s electrical system — and most residential circuits aren’t perfectly stable. Modern LED strings are especially sensitive to voltage fluctuations. A momentary spike above 125V (common during HVAC startup, lightning-induced surges, or utility grid switching) can overstress the tiny driver ICs inside each bulb. Incandescent strings fare slightly better under overvoltage but suffer dramatically under undervoltage: when line voltage drops below 110V, filament temperature falls, increasing resistance inconsistency and accelerating tungsten evaporation at weak spots in the coil.

According to the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), 23% of decorative lighting failures reported between 2019–2023 were linked to power quality issues — not bulb defects. Older neighborhoods with aging transformers and shared neutral lines experience greater variance, making lights on the same street behave unpredictably: one string lasts three years; its neighbor dies before New Year’s Eve.

2. Heat Accumulation and Poor Ventilation

Heat is the silent killer of both incandescent and LED bulbs — though for different reasons. In traditional mini-lights, the filament operates near 2,500°C. Even minor insulation around the socket (e.g., lights tucked behind thick garlands, wrapped tightly around metal railings, or buried under fake snow) traps heat and raises ambient temperature by 15–30°C. That extra thermal load accelerates tungsten migration, thinning the filament until it fractures.

LEDs generate less heat overall, but their internal drivers and phosphor coatings degrade rapidly above 60°C. A study by Underwriters Laboratories found that LED strings mounted directly against vinyl siding — which absorbs and re-radiates solar heat — experienced 4.7× higher failure rates than identical strings hung on open eaves. The culprit? Sustained junction temperatures exceeding 85°C during daytime hours, even in winter.

3. Manufacturing Quality and Component Tiering

Not all “200-light LED strings” are built alike. Reputable brands use Class II-rated capacitors, thermally stable epoxy encapsulants, and gold-plated contacts. Budget imports often substitute aluminum wire bonds for copper, use ceramic capacitors rated for only 85°C (not the required 105°C), and omit conformal coating on printed circuit boards. These cost-cutting measures become visible only after thermal cycling — expansion and contraction from daily on/off cycles — exposes microfractures in solder joints or delamination in chip packaging.

The difference shows up in accelerated life testing. UL 588-compliant strings undergo 500 on/off cycles at 60°C ambient. High-tier products typically survive beyond 1,200 cycles with <2% luminance loss. Low-tier units frequently fail before cycle 200 — often with complete string dropout due to single-point failure in the controller.

| Component | High-Quality String | Budget String |

|---|---|---|

| LED Chip | Epistar or Cree die; bin-matched for consistent Vf | Unbranded generic die; wide forward-voltage variance (±0.3V) |

| Current Regulation | Constant-current driver per segment | Resistor-limited; no regulation |

| Socket Housing | Flame-retardant PBT plastic (UL94 V-0) | Recycled ABS plastic (no flame rating) |

| Wire Insulation | 105°C-rated PVC or TPE | 70°C-rated PVC (brittles in cold) |

| Connectors | Gold-plated brass; IP65 sealed | Nickel-plated steel; unsealed |

3. Environmental Exposure and Material Fatigue

Outdoor lights face a relentless assault: UV radiation degrades plastic housings and diffusers, causing micro-cracking that invites moisture ingress; salt spray corrodes contacts in coastal areas; freeze-thaw cycles embrittle wire jackets; and wind-induced vibration fatigues solder joints. A 2022 field audit by the Illuminating Engineering Society tracked 120 identical LED strings installed across four U.S. climate zones. After two seasons, failure rates varied widely:

- Desert Southwest (low humidity, high UV): 38% failure — mostly yellowing/diffuser cracking

- Great Lakes (freeze-thaw, road salt drift): 61% failure — primarily connector corrosion and wire jacket splitting

- Pacific Northwest (high humidity, mild temps): 22% failure — dominated by moisture-related short circuits

- Deep South (high heat/humidity, frequent storms): 54% failure — combination of thermal stress and condensation

Crucially, the same string model performed differently depending on mounting method. Strings hung loosely on gutters lasted 2.3× longer than those zip-tied to metal posts — vibration damping mattered more than expected.

4. Circuit Architecture: Series vs. Parallel vs. Hybrid Designs

This is where engineering choices create dramatic real-world consequences. Traditional incandescent mini-lights use series wiring: 50 bulbs share 120V, so each sees ~2.4V. If one bulb burns out, the entire string goes dark — unless it has a shunt wire (a tiny bypass fuse inside the bulb base). But shunts degrade over time. After repeated thermal cycling, their resistance rises, eventually failing to activate when needed. That’s why older strings often go dark in sections — not uniformly.

Modern LED strings use three approaches:

- Full-series: One driver powers all LEDs. A single open-circuit LED kills the whole string. Common in ultra-low-cost sets.

- Segmented-series: Groups of 10–20 LEDs share a local current regulator. Failure isolates only that segment — but poor thermal design can cause cascading regulator failure.

- True parallel (rare in consumer sets): Each LED has independent current limiting. Highest reliability — but highest cost and power consumption.

“Most ‘LED’ strings sold today are actually constant-voltage, resistor-limited arrays,” explains electrical engineer Dr. Lena Torres, who consults for major lighting manufacturers.

“They’re marketed as ‘energy efficient,’ but without proper current regulation, voltage drift across the string causes uneven current distribution. The first bulb gets 22mA, the last gets 18mA — and that imbalance accelerates lumen depreciation and thermal runaway in hotter positions.”

5. User Handling and Installation Errors

How lights are installed matters as much as what they’re made of. Twisting wires too tightly stresses conductors and creates micro-fractures in the copper strands. Using nails or staples through the cord damages insulation and invites shorts. Plugging multiple heavy-duty extension cords together increases resistance and voltage drop — dropping supply voltage at the far end of the string below operational thresholds. And perhaps most overlooked: leaving lights plugged in 24/7 during the season.

A University of Illinois study monitored 84 households using identical LED strings. Those who used timers (on 5pm–11pm only) saw 73% fewer failures than those who left them on continuously — not because of energy savings, but because thermal cycling was reduced from 24 cycles/day to just one.

Mini Case Study: The Elm Street Holiday Lights

In Portland, Oregon, two adjacent homes used the same brand and model of 300-light LED icicle lights purchased from a national retailer. Both were installed on December 1st. By December 22nd, House A’s lights were fully functional. House B’s string had 47 dead bulbs — concentrated in the lower third.

Investigation revealed key differences: House A mounted lights using insulated plastic clips spaced every 18 inches, allowing airflow. House B stapled the cord directly to cedar siding, compressing the insulation and trapping heat. More critically, House B ran the string through a 50-foot outdoor extension cord with 18-gauge wire (undersized for the 45-watt load), causing a 9.2V drop at the far end. That voltage sag forced the final segment’s driver ICs to operate outside spec — overheating and failing progressively. Once replaced with a 12-gauge cord and proper mounting, the replacement string lasted four full seasons.

6. Maintenance and Storage Habits

Improper storage guarantees premature failure. Coiling lights tightly around a cardboard tube stresses wire bends beyond their flex rating. Storing in damp basements promotes oxidation on contacts. Leaving them in attics exposes them to summer temperatures exceeding 45°C — accelerating capacitor electrolyte evaporation. Even dust accumulation on lenses reduces thermal emissivity, raising operating temperature by 3–5°C.

Light Storage Checklist

- ✅ Unplug and inspect for cracked sockets or frayed wires before storing

- ✅ Wind gently around a rigid spool (not your hand) — maintain minimum 3-inch bend radius

- ✅ Store in original box or ventilated plastic bin — never sealed garbage bags

- ✅ Keep in climate-controlled space (ideally 10–25°C, <60% RH)

- ✅ Label boxes with year purchased and location used (e.g., “Front Porch – 2023”)

7. FAQ: Real Questions from Homeowners

Why do LED lights sometimes burn out *faster* than old incandescent ones?

Early-generation LED strings (2010–2015) used low-cost drivers and inadequate thermal management. Their failure mode isn’t filament breakage — it’s electronic component degradation. A single failed capacitor or MOSFET can disable an entire segment. Modern, UL-listed LEDs last significantly longer — but only if matched with appropriate drivers and housing. Don’t compare 2024 LEDs to 1995 incandescents; compare equivalent-tier products from the same era.

Can I mix different brands or ages of light strings on one circuit?

Strongly discouraged. Mixing loads creates impedance mismatches and unpredictable current draw. Older incandescent strings may draw 5–10x more current than LEDs, overloading shared controllers or timers. Even mixing LED strings from different years risks forward-voltage mismatch — causing some bulbs to overdrive while others underperform, accelerating thermal stress across the chain.

Do “warm white” and “cool white” LEDs fail at different rates?

Yes — but not due to color temperature itself. Cool-white LEDs (5000K–6500K) typically use blue chips + yellow phosphor, which runs cooler and more efficiently. Warm-white variants (2700K–3000K) require additional red phosphors that absorb more energy and generate more heat at the chip level. In poorly ventilated fixtures, warm-white LEDs show 18–22% higher lumen depreciation after 5,000 hours.

Conclusion: Choose Smarter, Not Just Cheaper

Christmas lights shouldn’t be disposable. When you understand that premature burnout stems from measurable, avoidable factors — voltage instability, thermal stress, component tiering, environmental exposure, circuit design, handling errors, and storage neglect — you gain agency. You stop blaming “bad luck” and start making informed decisions: selecting UL-listed strings with proper thermal ratings, installing with airflow in mind, using appropriately gauged extension cords, and storing with intention. These habits don’t just extend bulb life — they reduce fire risk, lower seasonal electricity costs, and cut down on landfill waste. With the average household spending $35–$85 annually on replacement lights, investing 20 minutes in proper setup and storage pays for itself in under two seasons.

This holiday season, treat your lights like the engineered systems they are — not festive afterthoughts. Check your outlets with a simple voltage meter. Feel the warmth of bulbs mid-operation — if they’re too hot to touch comfortably after 15 minutes, reconsider placement. And when unpacking next November, pause before tossing last year’s string: examine the sockets, test the connectors, and ask whether the failure was preventable. Because the most reliable Christmas lights aren’t the cheapest ones — they’re the ones you understand deeply enough to protect.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?