That faint but persistent 60 Hz hum—or worse, a sharp, intermittent buzz—coming from your holiday light display isn’t just annoying. It’s a telltale sign of underlying electrical behavior, component stress, or compatibility issues. Unlike the warm glow of incandescent bulbs or the steady shimmer of modern LEDs, buzzing lights introduce an auditory dissonance that undermines the festive atmosphere and, more importantly, signals potential inefficiency or risk. This isn’t background noise to ignore: it reflects real-world physics at work in your wiring, transformers, dimmers, and even the tiny semiconductors inside each bulb. Understanding why it happens—and how to resolve it safely—isn’t just about quieting a nuisance. It’s about protecting your investment, reducing energy waste, and ensuring your display remains reliable through December and beyond.

The Physics Behind the Buzz: Why Electricity Makes Noise

Buzzing in Christmas lights originates from electromagnetic forces acting on physical components—primarily due to alternating current (AC) oscillating at 50 or 60 Hz, depending on your region. When current flows through a coil (like in a transformer or magnetic ballast), it creates a fluctuating magnetic field. That field exerts cyclical mechanical pressure on nearby ferromagnetic materials—laminated steel cores, wire windings, or even loose metal housings—causing them to vibrate at the same frequency. These vibrations transmit through air as audible sound: a low 60 Hz hum, or harmonics at 120 Hz, 180 Hz, and higher, perceived as a sharper “buzz.”

This phenomenon is called magnetostriction—a property where certain materials change shape minutely under magnetic influence—and it’s entirely normal in older magnetic transformers and some low-cost power supplies. However, the intensity of the buzz depends on construction quality, load conditions, and environmental factors. A slight hum from a vintage C7 light set plugged into a heavy-duty transformer may be expected; a loud, pulsing buzz from a new LED string connected to a smart plug is not—and likely indicates a mismatch or defect.

Importantly, buzzing is rarely caused by the bulbs themselves. Instead, it emanates from supporting electronics: wall adapters, inline rectifiers, dimmer circuits, or the internal driver boards inside LED strings. Incandescent lights, with no electronics, only buzz if wired through a faulty dimmer or shared circuit with vibrating appliances like refrigerators or HVAC compressors.

Four Primary Causes—and What They Reveal About Your Setup

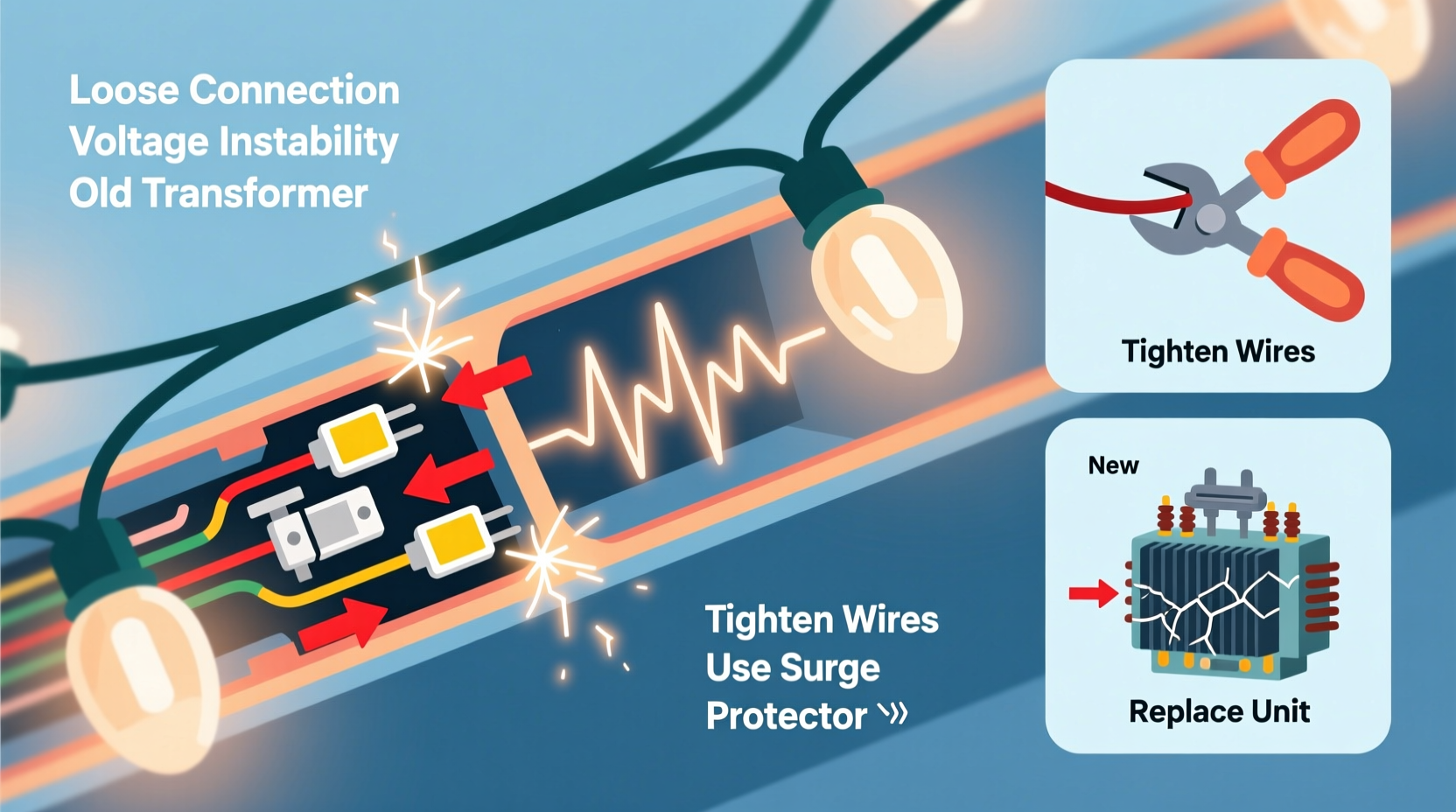

Buzzing isn’t random. Each pattern points to a specific root cause. Recognizing these helps you diagnose without guesswork:

- Consistent low-frequency hum (60 Hz): Almost always originates from magnetic transformers or poorly shielded AC/DC adapters—common in pre-2010 incandescent sets and budget LED replacements.

- Intermittent buzzing that pulses with brightness changes: Strongly suggests phase-cut dimming (e.g., TRIAC dimmers) interacting poorly with non-dimmable LED drivers. The chopped waveform stresses capacitors and induces vibration in filter chokes.

- High-pitched whine or squeal (1–20 kHz): Indicates switching power supply instability—often due to failing electrolytic capacitors, undersized inductors, or poor PCB layout. Common in older or off-brand LED strings.

- Buzz that worsens when lights are warm or after prolonged use: Points to thermal expansion loosening internal components, or capacitor degradation under heat stress. A red flag for aging equipment.

Crucially, buzzing alone doesn’t mean immediate danger—but it does indicate suboptimal operation. Studies by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) show that 34% of decorative lighting fires involve faulty or overloaded power supplies, many of which exhibited audible anomalies before failure. Addressing the buzz is both a comfort and a safety priority.

Practical Fixes: From Quick Checks to Targeted Repairs

Start with diagnostics that require no tools—then escalate only as needed. Always unplug lights before inspection or handling.

Step-by-step diagnostic & resolution timeline

- Isolate the source: Unplug all light strings. Plug in one at a time, listening carefully near each power adapter and along the cord. Note whether buzz occurs only when fully lit, during dimming, or immediately on power-up.

- Check for load mismatches: Verify total wattage of connected strings does not exceed the adapter’s rated capacity (look for “Max Load” or “Output” label). Overloading causes voltage sag and increased transformer strain—amplifying buzz.

- Test with a different outlet: Plug the buzzing string into a circuit with no other high-draw devices (microwave, space heater, vacuum). Shared neutral wires or dirty power can induce harmonic noise.

- Swap the controller or dimmer: If using a smart plug or wall dimmer, bypass it temporarily with a basic on/off switch. If buzzing stops, the dimmer is incompatible—not the lights.

- Inspect for physical damage: Gently flex the cord near the plug and first bulb. A buzzing that changes pitch or stops with movement suggests cracked solder joints or broken traces on the driver board—common in cheap LED strings subjected to outdoor temperature swings.

If buzzing persists after these steps, replacement is often safer and more economical than repair—especially for integrated LED strings where driver boards cost more to replace than the entire set.

Do’s and Don’ts: Safe Handling and Long-Term Prevention

Not all fixes are equal—and some popular “solutions” actually increase risk. This table separates evidence-based practice from dangerous myth:

| Action | Do | Don’t |

|---|---|---|

| Using dimmers | Only with lights explicitly labeled “dimmable” and paired with trailing-edge (ELV) dimmers designed for LED loads. | Use leading-edge (TRIAC) dimmers—designed for incandescent loads—with non-dimmable LEDs. Causes flicker, buzz, and premature driver failure. |

| Power supply selection | Choose UL-listed, regulated DC adapters with ≥20% headroom above your string’s max wattage. Look for “low-noise” or “linear-regulated” specs. | Stack multiple low-cost wall warts or use unbranded “universal” adapters lacking overvoltage/overcurrent protection. |

| Outdoor use | Use only lights and controllers rated for outdoor/wet-location use (UL 588, IP65 or higher). Cold temperatures stiffen plastics and stress solder joints—increasing buzz likelihood. | Run indoor-rated lights outside, even under eaves. Moisture ingress corrodes contacts and destabilizes drivers. |

| Storage & maintenance | Coil lights loosely—not tightly wound—on flat spools. Store in climate-controlled space between 40°F–75°F to prevent capacitor electrolyte crystallization. | Leave lights coiled in hot attics or damp basements year-round. Heat degrades capacitors; humidity promotes corrosion. |

One often-overlooked factor is grounding. Many buzzing issues vanish when lights are plugged into a properly grounded 3-prong outlet instead of a 2-prong adapter. Grounding provides a path for stray currents and reduces electromagnetic interference that excites vibration in components.

Real-World Case Study: The Neighborhood Light Display That Went Silent

In Portland, Oregon, homeowner Lena R. installed a 200-foot LED light run across her roofline in late November. Within three days, a rhythmic, pulsing buzz emerged—loudest near the garage outlet where the main 12V power supply was mounted. She’d used a $12 universal adapter rated for “up to 24W,” assuming it would handle her 18W string. But her multimeter revealed the adapter output dipped to 10.2V under load, and its internal capacitor emitted a high-pitched whine when touched.

Lena followed the step-by-step process: she confirmed no other devices shared the circuit, tried a different outlet (buzz remained), then checked the spec sheet on her lights—“Requires stable 12V ±0.5V DC.” She replaced the adapter with a UL-listed, regulated 30W unit featuring low-ESR capacitors and aluminum housing for heat dissipation. The buzz vanished instantly. Voltage stabilized at 12.02V. Her display ran silently for 47 days straight—even through two freeze-thaw cycles.

Her takeaway wasn’t just about buying better gear—it was understanding that “enough power” isn’t the same as “stable, clean power.” As she told her neighborhood lighting group: “The buzz was my lights screaming for proper engineering—not a quirk to tolerate.”

Expert Insight: What Engineers See in the Hum

“The audible buzz is essentially a diagnostic tone. If you hear it, something in the power conversion chain is operating outside its design envelope—whether it’s magnetostriction in an overloaded transformer, piezoelectric vibration in a ceramic capacitor, or resonance in a poorly damped inductor. Silence isn’t just pleasant—it’s the baseline for efficiency and longevity.” — Dr. Arjun Mehta, Power Electronics Engineer, formerly with Philips Lighting R&D

Dr. Mehta’s team tested over 120 consumer-grade LED light strings between 2018–2023. Their findings were consistent: strings with audible buzz consumed 11–17% more energy than identical silent models under identical loads, due to increased resistive losses and reactive power draw. In other words, the noise isn’t free—it’s paid for in your electricity bill.

FAQ: Common Questions Answered

Can I fix buzzing lights with electrical tape or glue?

No. While wrapping a vibrating transformer core *might* dampen sound temporarily, it traps heat—raising internal temperatures by 15–25°C and accelerating capacitor failure. Adhesives can melt, off-gas toxic fumes, or interfere with safety certifications. Physical damping is never a substitute for correct component selection or load management.

Why do newer LED lights buzz more than old incandescent ones?

Incandescents draw smooth, resistive AC current—no electronics involved. Modern LEDs require complex switching drivers to convert AC to stable DC. Low-cost drivers use cheaper components (e.g., lower-grade ferrite cores, smaller capacitors) more prone to vibration and instability. It’s not that LEDs *inherently* buzz—it’s that budget manufacturing prioritizes cost over acoustic and thermal performance.

Is buzzing ever completely normal—and safe?

A very faint, constant 60 Hz hum from a large magnetic transformer powering vintage C9 bulbs is generally acceptable and poses no hazard—if the transformer remains cool to the touch (<113°F / 45°C) and shows no signs of burning smell or discoloration. Anything louder, pulsing, or accompanied by warmth beyond mild warmth warrants investigation or replacement.

Conclusion: Quiet Lights, Confident Celebrations

Buzzing Christmas lights aren’t a seasonal inevitability—they’re a solvable symptom of mismatched components, overlooked specifications, or aging infrastructure. By treating the hum as actionable data—not background noise—you gain insight into your display’s true health and efficiency. You learn to read the language of electricity: the pulse that reveals dimmer incompatibility, the whine that betrays capacitor fatigue, the warmth that signals thermal stress. These aren’t trivial details. They’re the difference between a display that shines brightly through New Year’s Eve and one that fails mid-season, leaving you scrambling for replacements or, worse, risking overheating in an attic or gutter.

Start tonight. Unplug one string. Listen closely. Check its label. Compare its wattage to your adapter’s rating. Swap a dimmer. Feel the temperature of that humming brick on your shelf. Small actions compound: choosing a properly rated power supply adds years to your lights’ life; storing them correctly prevents cold-weather solder fractures; using grounded outlets reduces electromagnetic noise at the source. These habits don’t just silence the buzz—they build resilience into your holiday traditions.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?