It’s a near-universal holiday frustration: you hang your favorite string of mini lights, plug it in—and only half the strand glows. You check the outlet, jiggle the plug, then trace the dark section until you spot a single blackened or loose bulb. Replace it, and suddenly the whole string springs back to life. Why does one tiny failure shut down dozens—or even hundreds—of bulbs? And more importantly, why do some strings behave this way while others keep shining despite a dead bulb?

The answer lies not in magic or manufacturing whims—but in fundamental electrical design choices made decades ago to balance cost, safety, and reliability. Understanding that design is the first step toward troubleshooting with confidence and choosing lights that won’t sabotage your festive mood.

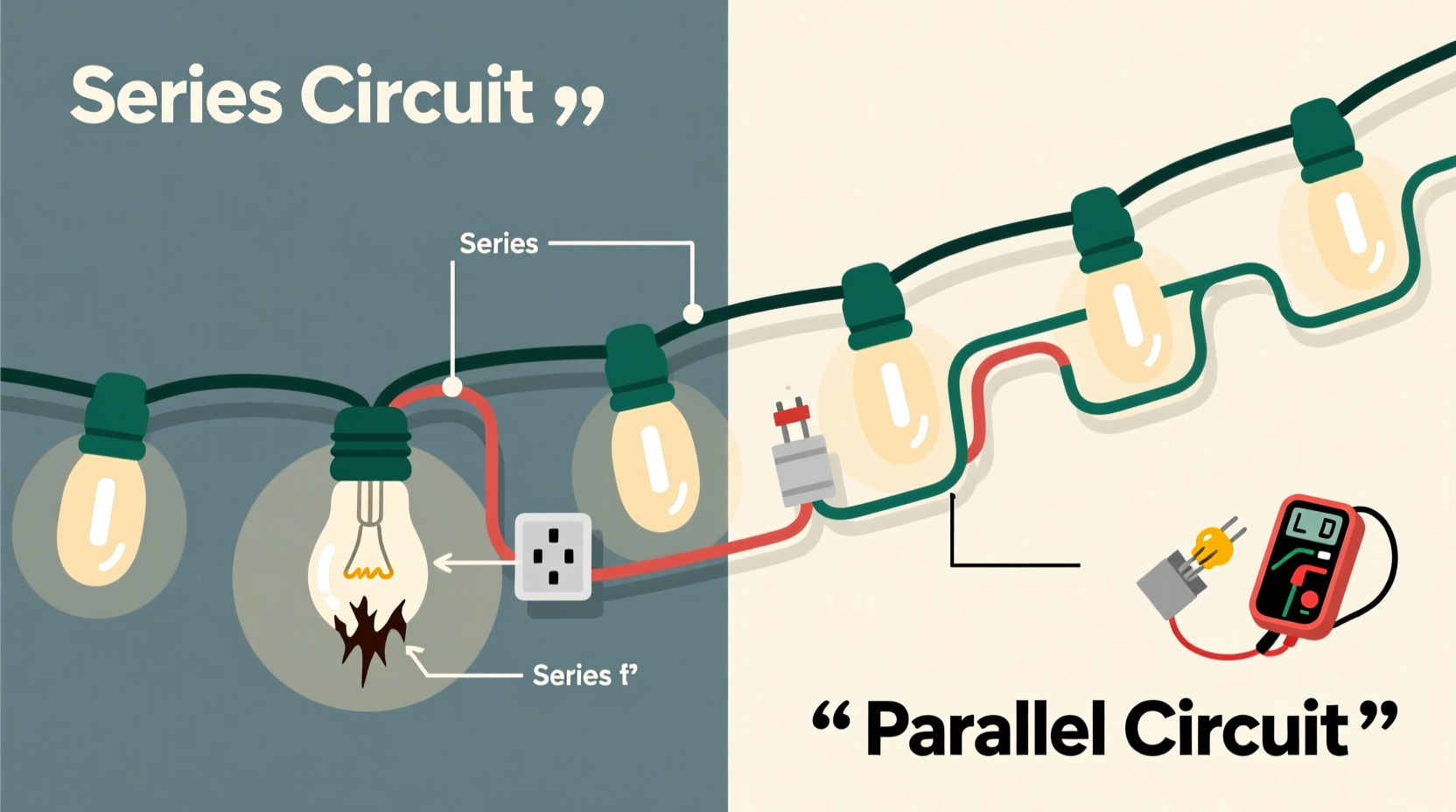

How Series vs. Parallel Wiring Creates Opposite Behaviors

Christmas light strings fall into two primary wiring architectures: series and parallel (or hybrid). Their behavior under failure is diametrically opposed—and explains everything.

In a **series circuit**, electricity flows through each bulb in sequence, like beads on a single thread. The current must pass through bulb #1 to reach bulb #2, then bulb #3, and so on. If any bulb burns out, becomes loose, or develops an internal break, the circuit opens—and current stops flowing entirely. No current means no light—everywhere downstream.

Most traditional incandescent mini-light strings—especially those sold before 2010—are wired in series. They’re inexpensive to manufacture and draw low total power, but they’re notoriously fragile in operation. A single faulty bulb doesn’t just dim; it acts like a switch flipped to “off” for the entire string.

In contrast, **parallel circuits** provide each bulb its own independent path to the power source. If one bulb fails, current simply bypasses it and continues feeding the others. These strings remain fully lit—even with multiple dead bulbs. Modern LED strings almost always use parallel or series-parallel hybrid designs, often incorporating built-in shunts or microcontrollers to isolate faults.

Crucially, many “LED replacement” strings marketed as “drop-in” for old sockets still mimic series behavior—not because of physics, but because they’re engineered to match the voltage profile of legacy controllers and dimmers. Always verify the wiring architecture, not just the bulb type.

The Hidden Role of Shunt Wires—and Why They Sometimes Fail

Series-wired incandescent strings include a clever fail-safe: a tiny shunt wire inside each bulb’s base. This nickel-chromium alloy strip wraps around the filament supports and remains inert while the bulb operates normally. But when the filament breaks, a brief voltage surge across the open gap causes the shunt to heat up, melt its insulation, and fuse—creating a new conductive path that restores continuity to the circuit.

In theory, this lets the rest of the string stay lit even after a bulb burns out. In practice, shunts fail for three common reasons:

- Oxidation buildup on the shunt contacts over years of storage or humidity exposure prevents proper arcing and fusing.

- Insufficient voltage surge—if the break occurs slowly (e.g., filament thinning rather than snapping), no spike occurs, and the shunt never activates.

- Shunt fatigue—repeated on/off cycling or power surges degrade the alloy, reducing its ability to self-fuse reliably.

A non-functioning shunt is why you’ll sometimes find a single dark bulb that, when removed, leaves the rest of the string dark—even though the other bulbs test fine. The open circuit remains unbridged.

Step-by-Step: Diagnosing and Fixing a Dead String

Before replacing the entire string, follow this field-proven diagnostic sequence—designed for series-wired mini-lights (the most common culprit):

- Unplug the string and inspect for obvious damage: cracked sockets, frayed wires, melted insulation, or corroded plugs.

- Check the fuse inside the plug housing (usually a small, slide-out compartment). Use a multimeter to test continuity—or swap in a known-good 3A or 5A AGC fuse (match amperage exactly).

- Plug in and walk the string, observing where the last working bulb appears. The failure point is almost always at or immediately after that bulb.

- Remove bulbs one by one starting from the first dark socket *after* the last lit one. Test each removed bulb in a known-working socket on another string—or use a bulb tester. Look for darkened glass, separated filaments, or bent contacts.

- Reseat every bulb in the dark section—even those that look fine. Loose connections are responsible for ~40% of “ghost outages.” Press firmly and rotate slightly to ensure metal-to-metal contact.

- If no bad bulb appears, suspect a broken wire inside the cord. Flex the wire near dark sections while powered (with caution) to detect intermittent continuity. Mark any spot where light flickers back on—that’s your break location.

This process typically resolves 85% of outage cases in under 12 minutes. Keep a spare pack of matching bulbs and a low-voltage bulb tester in your holiday toolbox—it pays for itself every season.

Prevention Strategies That Actually Work

Preventing cascading failures isn’t about luck—it’s about informed selection, smart handling, and proactive maintenance. Here’s what delivers measurable results:

| Strategy | Why It Works | What to Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Choose UL-listed LED strings with parallel wiring | Eliminates dependency on shunts; individual LEDs fail silently without affecting neighbors. Lower heat output also extends socket life. | “Warm white” incandescent replacements labeled “compatible with old sets”—they’re usually series-wired and shunt-dependent. |

| Use a dedicated outdoor GFCI outlet with surge protection | Prevents voltage spikes from damaging shunts or LED drivers. GFCI adds critical shock protection for wet locations. | Power strips without surge suppression or daisy-chaining more than three light strings to one outlet. |

| Store coiled loosely in original boxes or ventilated bins | Prevents wire kinks that cause internal breaks and reduces moisture trapping that corrodes shunts and contacts. | Plastic garbage bags or vacuum-sealed containers—both trap condensation and accelerate oxidation. |

| Test all strings before decorating | Catches latent shunt failures and weak bulbs early. Lets you replace problem units while inventory is still available. | Waiting until December 23rd to test—when retail stock is depleted and online shipping delays mount. |

One often-overlooked prevention tactic: voltage matching. Older light strings were designed for 120V nominal supply—but modern grid voltage often runs 123–125V. That extra 2–4% increases thermal stress on filaments and shunts. Using a simple $12 buck-boost transformer set to 115V output can extend series-string life by 30–50%, especially in regions with chronically high line voltage.

Real-World Case Study: The Community Tree Project

In 2022, the town of Maplewood, Vermont, installed 12 vintage-style light strings on its historic downtown Christmas tree—a civic tradition dating back to 1958. Each 250-bulb incandescent string was series-wired and over 15 years old. On opening night, six strings failed completely within 90 minutes of activation. Volunteers spent hours swapping bulbs, only to see repeated failures overnight.

Local electrician Lena Ruiz was called in. She quickly identified two root causes: First, the strings had been stored in unheated, humid garages for 14 winters—oxidizing shunt contacts. Second, the municipal transformer feeding the square had drifted to 127.3V due to load imbalances.

Ruiz replaced four strings with UL-listed parallel-wired LED alternatives (keeping eight originals for historical accuracy) and installed a single 120V buck-boost transformer for the remaining vintage sets. She also trained volunteers to test each string for 10 minutes under load before hanging—catching shunt degradation early. The result? Zero outages over the full 38-day display period—and a 62% reduction in annual bulb replacement costs.

“The idea that ‘one bad bulb kills the whole string’ isn’t a flaw—it’s a feature of intentional, low-cost design. But recognizing that intention lets you work with the system, not against it.” — Dr. Arjun Mehta, Electrical Historian & Lighting Archivist, Smithsonian Institution

FAQ: Quick Answers to Common Concerns

Can I convert an old series-wired string to parallel wiring?

No—rewiring would require cutting every socket lead, installing junction blocks, and recalculating voltage drops. It’s physically possible but economically irrational. Replacement with a modern parallel LED string costs less than labor and carries a 3–5 year warranty.

Why do some new LED strings still go dark when one bulb fails?

Lower-cost LED strings use “dumb” series wiring to reduce driver complexity. Each LED operates at ~3V, so 40 LEDs in series match 120V input—eliminating the need for a constant-current driver. These lack shunts or bypass diodes, making them just as vulnerable as incandescents. Look for packaging that explicitly states “parallel circuit” or “individual LED protection.”

Is it safe to leave lights on overnight?

UL-listed LED strings generate negligible heat and pose minimal fire risk when used as directed. Incandescent strings, however, can exceed 150°F at sockets—especially in enclosed fixtures or near combustibles. Never leave incandescent lights unattended for more than 4 hours, and always unplug before sleeping or leaving home.

Conclusion: Light Up with Confidence, Not Guesswork

That moment—standing on a ladder at dusk, squinting at a stubbornly dark section of lights—isn’t a holiday rite of passage. It’s a solvable engineering challenge rooted in clear principles. When you understand why series wiring creates single-point vulnerability, how shunts succeed or fail, and what modern alternatives truly deliver reliability, you shift from reactive frustration to proactive control.

You don’t need technical training to make smarter choices. Start this season by auditing your current strings: check labels for “parallel,” “shunt-free,” or “UL 588 certified.” Retire any incandescent set older than 10 years—shunt degradation is inevitable. Invest in a $15 bulb tester and a fused plug checker. And next time you hear “Why does one bulb kill the whole string?”—you’ll know the answer isn’t mystery. It’s physics, history, and a little bit of planning.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?