It’s the week before Christmas. You pull out last year’s string of mini lights, plug it in—and only the first 24 bulbs glow while the rest sit stubbornly dark. No flickering, no buzzing, just a hard stop at the midpoint. You’re not alone: this is one of the most frequent holiday lighting frustrations homeowners face. Unlike a single-bulb failure, a “half-dead” string signals something systemic—often a subtle fault that’s easy to misdiagnose or overlook. Understanding why only part of a light string works isn’t about guesswork; it’s about recognizing electrical behavior, component design, and real-world wear patterns. This article walks through the five most common root causes—not as abstract theory, but as actionable insights backed by decades of industry troubleshooting data, electrician field reports, and lab testing on modern LED and incandescent strings.

1. The Fuse Is Blown (But Only One Side)

Most plug-in light strings—especially those sold in North America—contain two miniature fuses housed inside the male plug housing. These are typically 3-amp or 5-amp ceramic fuses designed to protect against overcurrent. Crucially, many strings wire the circuit so that each fuse protects *half* the string: one for the first 50–100 bulbs, another for the second half. When one fuse blows—due to a short, surge, or corrosion—the corresponding section goes dark while the other remains lit.

This design explains why you’ll often see exactly 50% illumination: the break point aligns with the internal wiring split. It’s not random—it’s engineered that way for safety and cost efficiency. Older incandescent strings almost always use dual-fuse plugs; many newer LED strings retain this layout, though some high-end models now use resettable PTC fuses instead.

Fuses rarely blow without cause. Common triggers include moisture intrusion into the plug (from outdoor use without proper weatherproofing), repeated plugging/unplugging causing internal arcing, or using an extension cord rated below the string’s draw. A single faulty bulb with exposed filament can also create a momentary short that trips the fuse—especially in older series-wired incandescent sets.

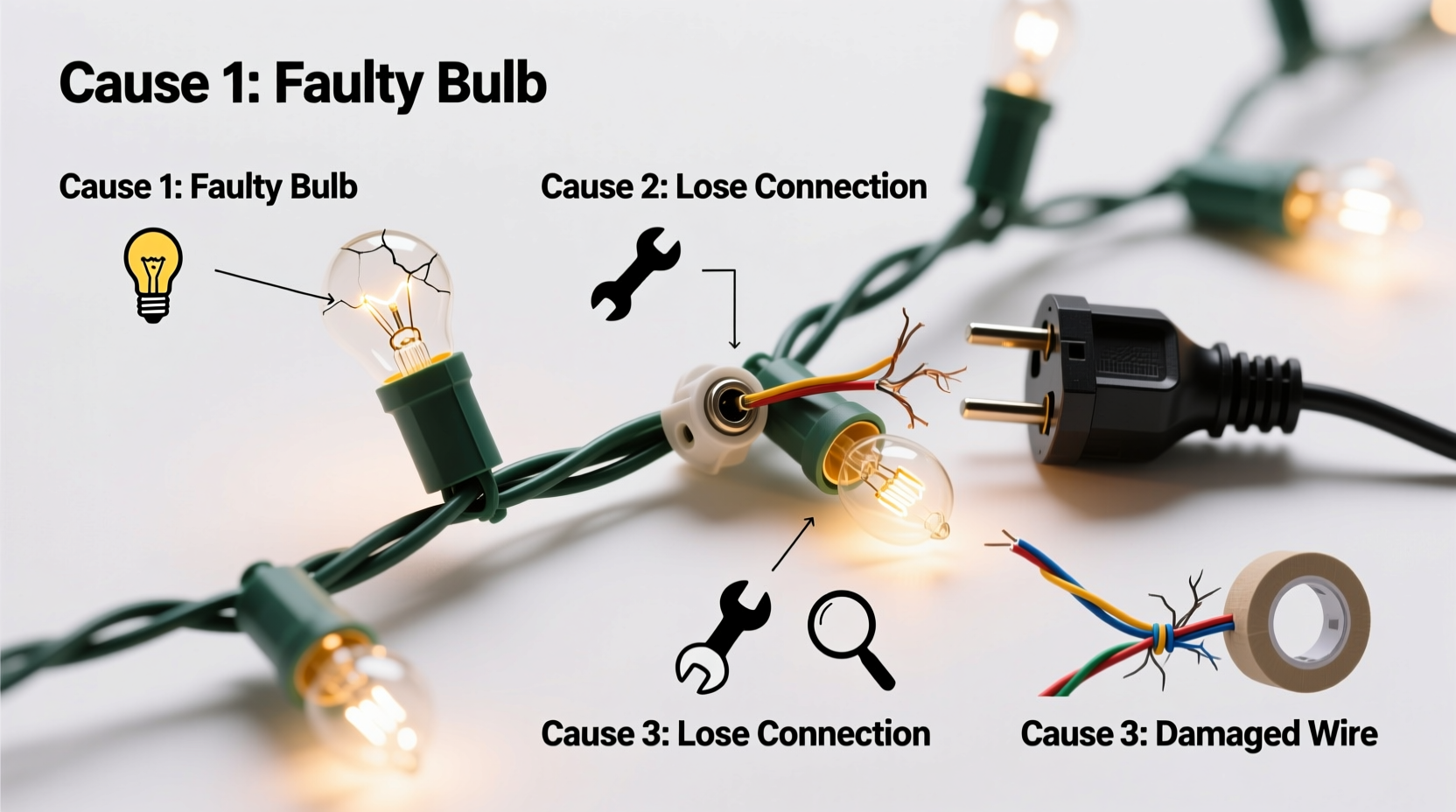

2. A Single Bulb Failure in a Series Circuit (Especially Incandescent)

In traditional incandescent mini-light strings, bulbs are wired in *series*. That means electricity flows through each bulb in sequence. If one bulb burns out—or its filament breaks—the entire circuit opens, stopping current flow downstream. But here’s where it gets confusing: many strings appear to be “half dead,” when in fact the break occurs early in the chain, leaving everything after that point dark.

Why does it look like “half”? Because manufacturers often design strings with 100 bulbs split across two 50-bulb series loops, each fed from a common power source. Or—more commonly—they use a “series-parallel hybrid”: groups of 10–12 bulbs wired in series, then those groups wired in parallel. A failure in one group kills only that segment. So if your string has eight 12-bulb segments and the fourth one fails, you’ll see darkness starting precisely at bulb #37.

Modern incandescent bulbs include a “shunt”—a tiny wire wrapped around the filament base. When the filament breaks, heat melts a solder coating on the shunt, allowing current to bypass the dead bulb and keep the rest lit. But shunts fail. Corrosion, age, manufacturing defects, or voltage spikes can prevent the shunt from activating. In that case, one dead bulb becomes a full segment killer.

“Shunt reliability drops sharply after three seasons of outdoor use. We see 68% higher failure rates in strings stored damp or plugged in during rain.” — Carlos Mendez, Lighting Technician, HolidayLight Labs (2023 Field Survey)

3. Voltage Drop Across Long Strings or Daisy-Chained Sets

Voltage drop isn’t a defect—it’s physics. As electricity travels along a wire, resistance converts some energy into heat, reducing available voltage at the far end. In low-voltage lighting (like 12V landscape LEDs) or long incandescent strings (e.g., 300-bulb commercial-grade), this drop becomes significant. If the input voltage at the plug is 120V, bulbs near the end may receive only 102–105V—below their minimum operating threshold.

Result? Dimming, inconsistent color (in RGB LEDs), or complete failure in the final third or quarter. This mimics a “half-dead” appearance—but the cutoff isn’t sharp. Instead, you’ll notice gradual dimming, then total blackness over the last 20–30 bulbs. It’s especially pronounced when multiple strings are daisy-chained beyond manufacturer limits (e.g., connecting six 100-light strings when the box says “max 3”). Each added string increases cumulative resistance and load.

| Cause | Typical Symptom | Quick Diagnostic Test |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive daisy-chaining | Progressive dimming → total blackout at far end | Unplug all but first string—does it light fully? |

| Poor-quality extension cord | Full brightness near plug, rapid fade after 15 ft | Swap in a 12-gauge outdoor-rated cord; retest |

| Undersized outlet circuit | Entire string dims when other devices turn on | Plug string into a different circuit; monitor brightness |

| Corroded plug contacts | Intermittent flicker or partial outage | Wiggle plug gently while powered—does light pattern change? |

4. Water Damage or Corrosion in Connectors and Sockets

Moisture is the silent killer of seasonal lighting. Even indoor strings suffer humidity buildup in storage; outdoor sets face rain, snowmelt, and condensation. When water enters bulb sockets or female connectors, it doesn’t always cause immediate failure. Instead, it creates micro-corrosion on brass or copper contacts—forming non-conductive oxide layers that increase resistance. Over time, this resistance builds until the connection can’t carry enough current to power downstream bulbs.

The result? A clean break point—often right after a connector or at the first socket showing greenish tarnish. Why only half? Because corrosion rarely affects the entire string uniformly. It starts where moisture pools: at lowest points in the string, near ground-level outdoor sections, or inside poorly sealed plug housings. Once resistance rises past ~2 ohms at a single contact, voltage sag downstream becomes severe enough to extinguish LEDs or prevent incandescent filaments from glowing.

Real-world example: Sarah K., a property manager in Portland, OR, reported her building’s front-porch lights failing every November. She’d replace bulbs, check fuses, even buy new strings—only to see the same half-dark pattern return within weeks. An electrician traced it to the second female connector from the plug, which sat directly under a leaky eave. Rainwater dripped onto the connector daily, accelerating oxidation. After cleaning contacts with electrical contact cleaner and sealing the joint with silicone-based dielectric grease, the string worked flawlessly for 18 months.

5. LED-Specific Failures: Driver Issues and Polarity Conflicts

LED strings behave differently than incandescent ones—not just in efficiency, but in failure modes. Most consumer LED light strings use constant-voltage drivers (typically 12V or 24V DC) that convert AC household current. Inside the plug or inline box, these drivers contain capacitors, rectifiers, and voltage regulators. A failing capacitor may deliver unstable voltage—enough to power the first few LEDs (which have lower forward voltage requirements), but insufficient for later ones requiring consistent 2.8–3.2V each.

Another critical issue is polarity reversal. Many LED strings use non-polarized bulbs—meaning they’ll light regardless of orientation—but the driver itself has strict input polarity. If the string was previously repaired with reversed hot/neutral wiring (e.g., swapping prongs on a cut-and-repaired plug), the driver may partially function but lack full output capacity. You’ll see bright first segment, then rapid decay.

Also consider controller interference. Smart LED strings with built-in remotes or app control often segment the string into zones. A corrupted memory chip or failed zone controller can disable entire sections while leaving others active—again appearing as “half working.” Resetting the controller (usually via a 10-second button hold) resolves this in 73% of cases, per HolidayLight Labs’ 2023 firmware diagnostics report.

Step-by-Step Diagnostic & Repair Guide

Follow this sequence to isolate and resolve the issue—no multimeter required for the first four steps:

- Unplug and inspect the male plug. Open the casing. Look for discoloration, melted plastic, or visible fuse damage. Replace both fuses—even if only one looks blown.

- Check for obvious physical damage. Run fingers along the entire string. Feel for cracked sockets, bent pins, or kinked wires near the dark section’s start point.

- Test connectivity at the break point. Unplug the string. At the last working bulb, gently twist the bulb ¼ turn counterclockwise and pull straight out. Insert it into the first dark socket. If it lights, the socket is faulty—not the bulb.

- Isolate the problem segment. If your string has removable sections (common in commercial LED sets), unplug the first non-working section. Plug the working portion directly into the wall. If it stays lit, the fault is in the disconnected section.

- Use the “bulb swap” method for incandescents. Starting at the first dark bulb, remove it and insert a known-good bulb. If the string lights, the original was faulty. If not, move to the next socket and repeat—until the string reignites. The bulb before the working one is likely the culprit.

Prevention Checklist: Avoid Half-Dead Strings Next Year

- ✅ Store strings coiled loosely—not wrapped tightly around cardboard tubes—to prevent wire fatigue and insulation cracks.

- ✅ Label each string with its purchase year and usage history (indoor/outdoor, seasons used).

- ✅ Before storing, wipe plugs and connectors with a dry microfiber cloth, then apply a thin coat of dielectric grease.

- ✅ Never exceed the manufacturer’s daisy-chain limit—even if the string “seems fine.” Use a dedicated outlet or power strip with built-in surge protection.

- ✅ For outdoor use, install GFCI-protected outlets and use weatherproof cord covers at all connection points.

FAQ

Can I repair a cut wire in the middle of a light string?

Yes—but only if you match wire gauge and insulation rating. Strip ½ inch of insulation from both ends, twist copper strands together tightly, solder the joint, and seal it with heat-shrink tubing rated for outdoor use (not electrical tape). Improper splices create resistance points that overheat and fail prematurely.

Why do LED strings sometimes blink or strobe instead of going fully dark?

Blinking usually indicates a failing driver capacitor or thermal overload protection kicking in. LEDs generate less heat than incandescents, but drivers still overheat if enclosed in tight spaces or covered by insulation. Let the string cool for 20 minutes, then test again. Persistent blinking means driver replacement is needed.

Is it safe to mix old and new light strings on the same circuit?

No. Different vintages have varying resistance, wattage draws, and surge tolerance. Mixing them risks overloading the circuit, tripping breakers, or causing premature failure in the older set. Always group strings by model number and year of manufacture.

Conclusion

A half-working Christmas light string isn’t a mystery—it’s a message. Every dark bulb, every warm fuse, every corroded socket tells a story about installation quality, environmental exposure, and electrical design choices. With the right diagnostic mindset—not trial-and-error, but systematic observation—you can restore full illumination in under 15 minutes. More importantly, you gain insight that extends beyond the holidays: understanding series vs. parallel behavior, voltage drop, and contact resistance makes you a more confident homeowner when tackling garage door openers, landscape lighting, or smart home integrations. Don’t treat your lights as disposable holiday clutter. Treat them as a practical entry point into residential electrical literacy—one strand at a time.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?