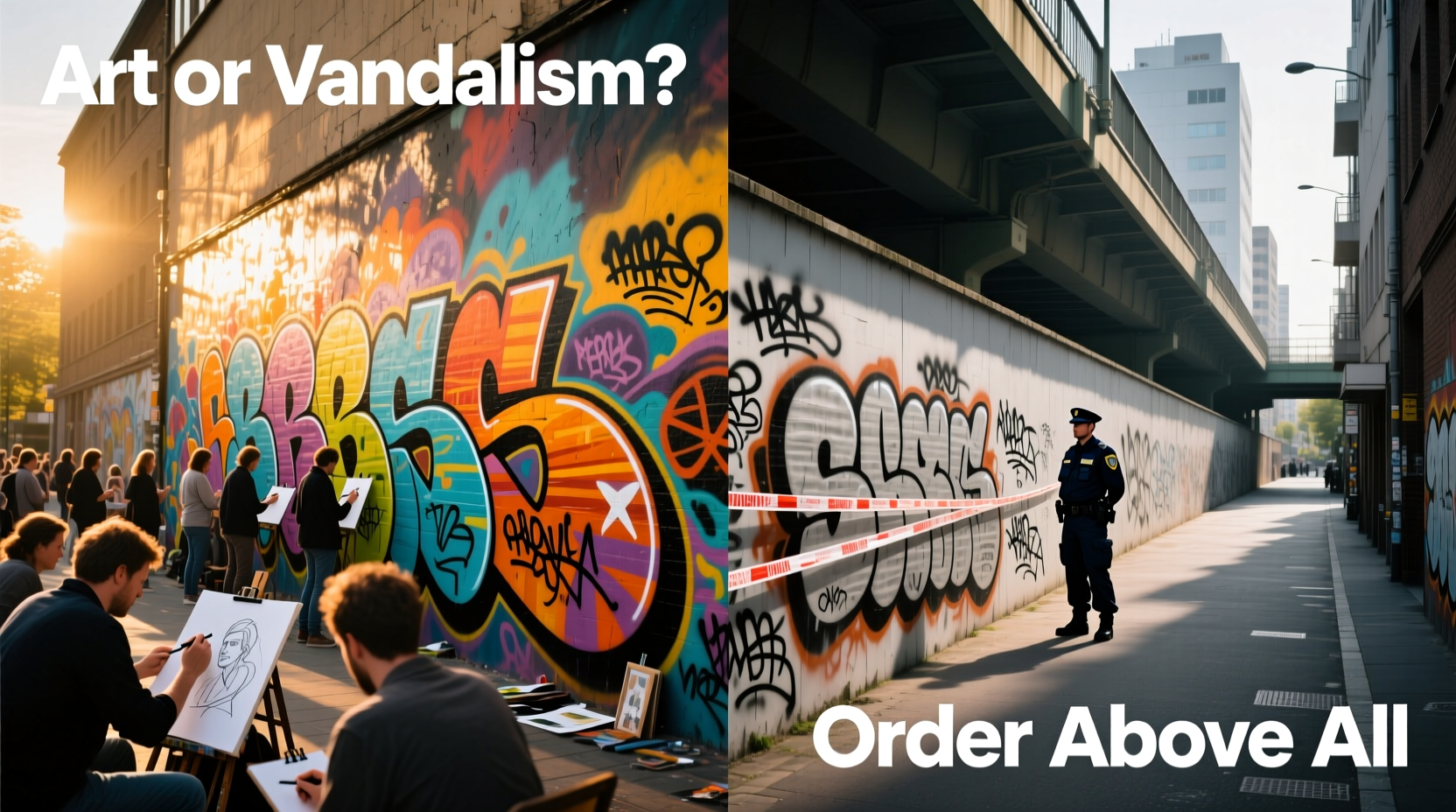

In the global conversation about public space and creative expression, few topics spark as much debate as graffiti. To some, it's vibrant, thought-provoking street art that transforms neglected walls into cultural landmarks. To others, it’s vandalism—a costly eyesore that undermines community standards and invites disorder. The stark contrast in how cities respond to graffiti reveals deep differences in values, governance, and urban philosophy. From Berlin’s celebrated murals to Singapore’s strict anti-graffiti laws, municipal policies reflect complex intersections of art, law, identity, and civic order.

This divergence isn’t random. It’s shaped by historical context, economic priorities, artistic legitimacy, and public perception. Understanding why certain cities welcome graffiti while others criminalize it offers insight into broader questions: Who owns public space? What defines art? And how can cities balance freedom of expression with social responsibility?

The Cultural Value of Graffiti as Art

In cities like Melbourne, São Paulo, and Barcelona, graffiti is not only tolerated but actively encouraged through designated zones, city-sponsored festivals, and partnerships with artists. These municipalities recognize that street art contributes to cultural vibrancy, tourism, and local identity. Large-scale murals often depict social commentary, celebrate heritage, or commemorate historical events, functioning as open-air galleries accessible to all.

Artists such as Banksy, Blu, and Os Gemeos have gained international acclaim, blurring the line between underground graffiti and institutionalized contemporary art. Their work has been exhibited in galleries and sold for millions—yet much of their most iconic pieces remain on city walls. This paradox underscores a growing acceptance: graffiti, when executed with skill and intent, can be powerful visual storytelling.

“Street art humanizes the urban landscape. It turns cold concrete into conversation.” — Dr. Lena Moreau, Urban Anthropologist, Sorbonne University

Cities that embrace graffiti often do so as part of a broader cultural strategy. For example, Melbourne’s laneways have become synonymous with creativity, drawing tourists eager to photograph ever-evolving artworks. The city supports this ecosystem by designating legal walls and working with collectives to manage output, ensuring that spontaneity coexists with accountability.

Legal and Social Perspectives on Vandalism

Conversely, many cities—including Tokyo, Dubai, and famously Singapore—maintain zero-tolerance policies toward unauthorized graffiti. In Singapore, offenders face fines up to SGD 2,000 and possible caning under the Vandalism Act of 1966. Public transportation systems are especially protected; even minor tagging can result in severe penalties.

These strict measures stem from a philosophy rooted in social order and cleanliness. Policymakers argue that unchecked graffiti signals neglect, encourages further rule-breaking (the “broken windows” theory), and imposes financial burdens on communities for cleanup. In high-density urban environments where appearance and functionality are tightly managed, graffiti is seen less as expression and more as disruption.

Moreover, not all graffiti is created equal. While elaborate murals may be admired, random tags, gang markings, or offensive symbols erode public trust. When cities lack mechanisms to distinguish between artistic contribution and defacement, blanket bans become easier to enforce than nuanced regulation.

Case Study: New York City’s Evolution on Street Art

No city illustrates the shifting perception of graffiti better than New York. In the 1970s and ’80s, subway graffiti was rampant, viewed widely as a symbol of urban decay. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority spent millions annually removing tags, and artists faced arrest and prosecution. Figures like Dondi, Lee Quiñones, and Lady Pink pushed boundaries despite risks, laying groundwork for what would later be recognized as a legitimate art movement.

By the 1990s, increased surveillance, harsher penalties, and cleaning protocols drastically reduced illegal train graffiti. However, the cultural energy didn’t disappear—it migrated. Galleries began showcasing former “taggers,” and brands hired street artists for campaigns. In the 2000s, neighborhoods like Bushwick in Brooklyn emerged as open-air museums, with property owners inviting artists to paint entire building facades.

Today, NYC operates a hybrid model: illegal tagging remains punishable, but the city permits murals in designated areas and funds public art programs. The Bushwick Collective, founded by local resident Joe Ficalora, curates large-scale works that attract thousands of visitors monthly. This transformation reflects a pragmatic compromise—acknowledging the cultural value of street art while maintaining control over its scope and location.

Factors Influencing Municipal Policies

Why do approaches vary so dramatically across cities? Several interrelated factors shape whether graffiti is embraced or banned:

- Economic Development Goals: Cities investing in tourism and creative economies are more likely to support street art as an asset.

- Political Climate: Authoritarian or highly regulated governments tend to prioritize order over dissenting expression.

- Public Opinion: Community attitudes toward art, youth culture, and public space heavily influence policy.

- Enforcement Capacity: Some cities lack resources to monitor or clean graffiti consistently, making prevention more appealing than management.

- Historical Context: Cities with strong traditions of muralism (e.g., Mexico City) naturally extend legitimacy to modern forms of public art.

| City | Graffiti Policy | Rationale | Notable Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melbourne, Australia | Encouraged in legal zones | Tourism, cultural identity | Laneway art districts attract millions yearly |

| Singapore | Banned with harsh penalties | Zero tolerance for disorder | Nearly graffiti-free public spaces |

| Berlin, Germany | Mostly tolerated; East Side Gallery preserved | Historical significance, artistic freedom | Iconic Cold War-era murals maintained |

| São Paulo, Brazil | Banned on private property; allowed on approved walls | Balance of control and expression | Vibrant street art scene within regulated framework |

| Tokyo, Japan | Strict enforcement, limited exceptions | Respect for property, social harmony | Minimal visible graffiti despite dense population |

How Cities Can Bridge the Divide

For cities torn between suppression and celebration, a middle path exists—one that honors both artistic freedom and civic responsibility. Successful models share common strategies:

- Create Legal Walls: Designate specific areas where artists can paint without fear of prosecution. These act as testing grounds and reduce pressure on unauthorized surfaces.

- Artist Licensing Programs: Register local artists, offer stipends or materials, and curate themes aligned with community values.

- Community Engagement: Involve residents in selecting mural topics and locations, fostering ownership and reducing conflict.

- Fast Response to Unauthorized Tags: Remove non-artistic vandalism quickly to prevent copycat behavior while preserving approved works.

- Educational Outreach: Partner with schools and arts organizations to teach youth about the difference between destructive tagging and constructive muralism.

Checklist: Steps for Cities Considering Graffiti Integration

- ✅ Assess existing public art infrastructure and community sentiment

- ✅ Identify low-risk zones for pilot mural projects

- ✅ Establish clear rules: what’s allowed, where, and by whom

- ✅ Partner with local artists and cultural nonprofits

- ✅ Implement rapid removal protocol for illegal graffiti

- ✅ Monitor impact on tourism, safety perceptions, and property values

- ✅ Adjust policies based on data and feedback

Frequently Asked Questions

Is graffiti always considered art?

No. While large, detailed murals are often recognized as artistic expression, random tagging, gang signs, or offensive content are typically classified as vandalism. The distinction lies in intent, skill, and consent. Legality and context play crucial roles in how graffiti is perceived.

Can graffiti reduce crime or improve neighborhoods?

In some cases, yes. Well-maintained street art can deter apathy and neglect, which are linked to higher crime rates. Projects like Philadelphia’s Mural Arts Program have correlated large-scale public art with reduced graffiti and improved community morale. However, these benefits depend on sustained investment and community involvement—not just one-off paintings.

Do graffiti artists get paid in supportive cities?

Increasingly, yes. Many cities commission artists for public works, and private property owners pay for building murals. Festivals and cultural grants also provide income opportunities. In places like Lisbon and Detroit, street art has become a viable career path when integrated into formal programs.

Conclusion: Reimagining Public Space

The debate over graffiti isn’t merely about paint on walls—it’s about who gets to shape the visual language of our cities. As urban centers evolve, rigid binaries between “art” and “vandalism” are giving way to more nuanced frameworks. The most forward-thinking cities don’t simply ban or bless graffiti; they create systems where creativity thrives within shared boundaries.

Embracing graffiti as art requires trust—in artists, in communities, and in the idea that beauty can emerge from spontaneity. But banning it outright risks silencing voices that challenge, inspire, and reflect the pulse of city life. The future of urban aesthetics may lie not in prohibition or permission alone, but in collaboration: a dialogue between creators and citizens, painted one wall at a time.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?