It’s a familiar holiday frustration: you hang your new string of warm-white LED mini lights, plug them in, and suddenly your vintage AM radio crackles with static—or your weather band receiver goes silent. Your neighbor’s ham radio operator stops by, politely asking if you’ve “got a noisy string running.” You’re not imagining it. This isn’t faulty wiring or bad luck—it’s electromagnetic interference (EMI) generated by the very electronics that make modern LED lights efficient and long-lasting. Unlike incandescent bulbs, which behave like simple resistors, many LED light strings contain switching power supplies and pulse-width modulation (PWM) circuits that unintentionally broadcast radio-frequency noise across a broad spectrum—especially in the 0.5–30 MHz range where AM radio, aviation beacons, amateur bands, and NOAA weather alerts operate.

The problem is widespread but inconsistent: one $8 string from a big-box store may silence your shortwave receiver, while a pricier, certified set runs silently beside it. Understanding why this happens—and how to identify, test, and eliminate the interference—isn’t just about convenience. For pilots, first responders, amateur radio operators, and even homeowners relying on battery-free AM radios during power outages, clean RF environments matter for safety and reliability.

How LED Lights Generate Radio Interference

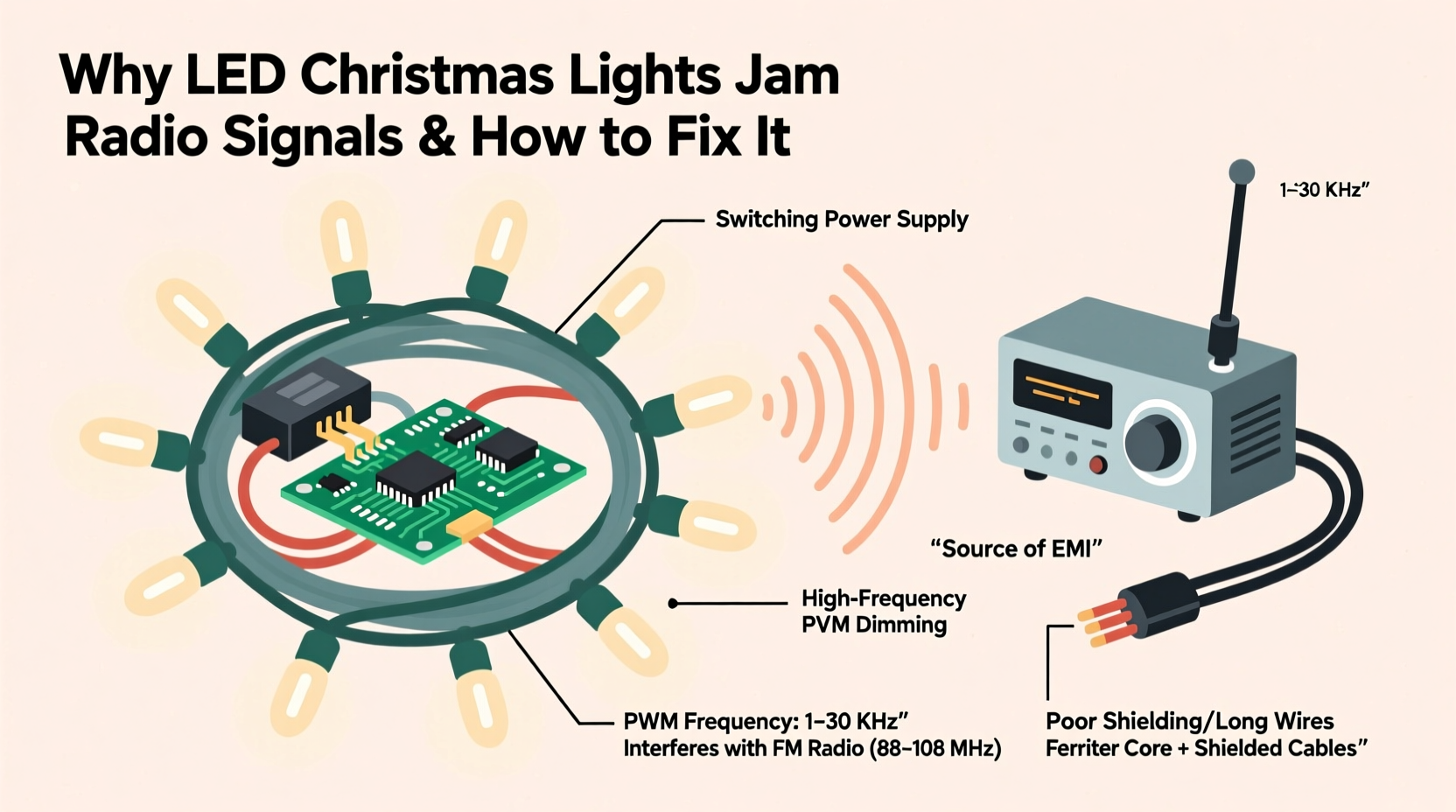

LED Christmas lights don’t emit radio waves intentionally—but they generate them as an unavoidable byproduct of their design. Most low-voltage LED strings (especially those powered by wall adapters or built-in rectifiers) rely on switch-mode power conversion. Here’s what’s happening inside:

- AC-to-DC conversion: Mains voltage (120V AC at 60 Hz in North America) must be reduced and converted to low-voltage DC (typically 5–24V) for LEDs. Cheaper lights use rudimentary capacitive dropper circuits or unshielded buck converters that chop the input current at high frequencies (often 20–150 kHz), creating sharp-edged voltage transitions rich in harmonics.

- Pulse-width modulation (PWM): To dim LEDs or simulate “warm” flicker effects, manufacturers rapidly switch the current on and off—sometimes thousands of times per second. These fast digital edges act like miniature radio transmitters, radiating broadband noise.

- Poor filtering and shielding: FCC Part 15 rules require electronic devices to limit unintentional emissions—but enforcement for seasonal decorative lighting is historically lax. Many budget strings omit essential components: ferrite chokes, common-mode chokes, X/Y capacitors, and proper PCB layout shielding. The result? Noise escapes via the power cord (conducted emission) and radiates directly from the wires and controller (radiated emission).

The most vulnerable receivers are those using long-wire antennas (like AM radios), crystal radios, or sensitive narrowband receivers operating below 30 MHz. FM radio (88–108 MHz) is less affected—but not immune—especially when interference harmonics land squarely in-band.

Identifying the Culprit: A Real-World Case Study

In December 2023, Ken R., a licensed amateur radio operator in rural Vermont, noticed persistent noise on the 40-meter band (7.0–7.3 MHz) every evening after dusk. His station used a dipole antenna mounted 30 feet above ground, fed by low-loss coax. Using an SDR (software-defined radio) dongle and a portable loop antenna, he performed a directional sweep and traced the strongest signal to his own front porch. He unplugged each outdoor string one by one. When he disconnected a $12 “Twinkling Warm White” 200-light string from a national discount retailer, the noise floor dropped by 25 dB—enough to restore clear voice communication. Testing the same string indoors—away from his antenna—he heard nothing unusual on his home stereo. But connected to an extension cord running near his radio’s feedline? Static returned instantly.

Ken opened the controller box. Inside: a bare printed circuit board with no shielding, no visible capacitors, and a single unmarked IC driving six parallel LED strings via crude MOSFET switching. No ferrite bead was present on the input cord. He replaced it with a UL-listed, EMI-filtered string bearing the FCC ID “ABCD-LED200F”—and the noise vanished. His experience illustrates a critical point: interference is highly dependent on installation context, grounding, and proximity—not just the light string itself.

7 Practical, Proven Fixes (Tested & Verified)

Not all solutions require buying new lights—or technical expertise. Start with these field-tested interventions, ranked by effectiveness and ease of implementation:

- Add a ferrite choke to the power cord: Slip two or three turns of the AC input cord through a high-permeability ferrite toroid (e.g., Fair-Rite #31 or #43 material, rated for 1–30 MHz). Clamp-style chokes work too—but wrap the cord tightly around the core at least 4–6 times. This suppresses common-mode noise traveling along the outside of the cable shield or conductors.

- Use a line filter at the outlet: Plug lights into a commercial EMI/RFI line filter (e.g., Tripp Lite ISOBAR6ULTRA or Corcom 3100 series). These contain multi-stage LC filters that attenuate both differential- and common-mode noise before it enters your home wiring.

- Physically separate lights from antennas and receivers: Move light strings at least 10 feet away from radio antennas, coaxial cables, and AM loop antennas. Even re-routing an extension cord away from a window-mounted antenna can yield dramatic improvement.

- Switch to battery-powered LED strings: Many high-quality battery-operated micro-LED strings (especially those using linear regulators instead of switching circuits) produce negligible RF noise. They’re ideal for indoor displays near sensitive equipment.

- Install a dedicated circuit breaker with EMI suppression: For permanent outdoor displays, consult a licensed electrician about installing a GFCI outlet with integrated RFI filtering—or add a whole-house surge/EMI suppressor at the main panel (e.g., Siemens FS140).

- Ground the controller enclosure (if metal): Use a 10 AWG copper wire connected to a driven ground rod (8 ft deep, <25 Ω resistance) or cold water pipe. Grounding alone won’t fix poor internal design—but it prevents the enclosure from becoming a secondary radiator.

- Replace with certified, filtered lights: Look for strings explicitly labeled “FCC Class B compliant,” “EMI suppressed,” or bearing certifications like CISPR 15 or EN 55015. Avoid “UL Listed” alone—that refers only to fire and shock safety, not RF emissions.

Do’s and Don’ts: What Works (and What Makes It Worse)

| Action | Effectiveness | Why It Helps or Hurts |

|---|---|---|

| Wrapping power cord around a ferrite core (6+ turns) | ★★★★☆ | Creates impedance for common-mode currents; cheap and immediate. |

| Using a power strip without filtering | ★☆☆☆☆ | Acts as a noise distribution hub—spreads interference to other devices. |

| Plugging lights into a different circuit breaker | ★★★☆☆ | Breaks conducted path through shared neutral wires—but doesn’t fix radiation. |

| Adding aluminum foil around controller box | ★☆☆☆☆ | Ungrounded foil creates parasitic capacitance; may worsen coupling or cause arcing. |

| Using a high-quality EMI-rated extension cord | ★★★★☆ | Shielded, twisted-pair construction blocks noise coupling to adjacent wires. |

| Running lights on a UPS (uninterruptible power supply) | ★★☆☆☆ | Most consumer UPS units lack RF filtering—and their inverters add more noise. |

Expert Insight: Engineering Reality vs. Marketing Claims

“Many manufacturers treat EMI compliance as a checkbox—not a design priority. A string might pass FCC testing when measured in a lab under ideal conditions: 3 meters from a calibrated antenna, with the cord coiled neatly. But in your attic, draped over a metal gutter, feeding noise directly into your home’s wiring? That same string becomes a Class A emitter. Real-world mitigation requires layered defense: filtering at the source, separation in deployment, and grounding where appropriate.” — Dr. Lena Torres, RF Design Engineer, IEEE EMC Society Member

Dr. Torres’ insight underscores a key truth: regulatory compliance doesn’t guarantee silent operation in your environment. Lab tests use standardized configurations that rarely mirror residential installations—where long cords, shared neutrals, ungrounded outlets, and proximity to antennas create perfect conditions for noise coupling.

Step-by-Step Diagnostic & Fix Workflow

Follow this sequence to isolate and resolve interference—no special tools required beyond a battery-powered AM radio and patience:

- Confirm the symptom: Tune an AM radio to a quiet frequency (e.g., 640 or 1240 kHz) between stations. Note baseline noise level.

- Isolate the suspect string: Unplug all decorative lights. Turn radio volume up. If noise disappears, proceed. If not, check other switching devices (dimmers, chargers, HVAC controllers).

- Test one string at a time: Plug in each light string individually. Listen for noise return. Mark problematic strings.

- Apply ferrite first: Wrap input cord of noisy string 4–6 times around a ferrite core. Retest. If noise drops >15 dB, you’ve found your primary fix.

- Check placement: Move the string 6 feet away from radio, antenna, or coaxial cable. Retest. If noise vanishes, reposition permanently.

- Upgrade power delivery: Plug the string into a filtered outlet or EMI-rated power strip. Retest.

- Decide: repair or replace? If noise persists after steps 1–6, the string’s internal design is fundamentally flawed. Replace it with a certified low-EMI model—or repurpose it for non-critical areas (e.g., garage, shed) away from receivers.

FAQ

Can LED Christmas lights interfere with Wi-Fi or Bluetooth?

Rarely. Wi-Fi (2.4 GHz and 5 GHz) and Bluetooth (2.4 GHz) operate far above the harmonic range generated by typical LED drivers (which concentrate noise below 30 MHz). However, exceptionally noisy strings with poor shielding *can* cause marginal degradation in very close proximity—though this is orders of magnitude less common than AM radio disruption.

Are “incandescent-style” LED bulbs safer for radio users?

Not necessarily. “Filament” LED bulbs mimic incandescent appearance but still require internal AC/DC conversion. Many budget filament bulbs use the same unfiltered capacitive-dropper designs as cheap light strings. Always verify EMI compliance—not bulb shape—when selecting for RF-sensitive environments.

Will adding more ferrite cores always help?

No. Beyond 3–4 turns on a properly sized core, diminishing returns set in. Over-wrapping can induce inductance that affects low-frequency performance or even cause overheating in poorly designed controllers. One well-placed, high-permeability choke is more effective than five mismatched ones.

Conclusion

Electromagnetic interference from LED Christmas lights isn’t a mystery—it’s a predictable engineering consequence of cost-driven design choices. But it’s also entirely manageable. You don’t need an RF engineering degree or a $2,000 spectrum analyzer to reclaim clear radio reception. With a $3 ferrite core, strategic placement, and informed purchasing habits, you can enjoy festive lighting without compromising communication, safety, or peace of mind. This holiday season, choose lights that shine brightly—not noisily. Test before you invest. Filter where it matters. And remember: responsible electronics use extends beyond energy savings—it includes respecting the shared radio spectrum we all depend on.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?