For many, cilantro is a vibrant, citrusy herb that brightens salsas, curries, and salads. For others, it’s an abomination—bitter, pungent, and unmistakably soapy. This sharp divide isn’t just pickiness or cultural preference. It’s written in our DNA. The reason some people perceive cilantro as tasting like soap lies in a fascinating interplay between genetics, olfactory receptors, and evolutionary biology. Understanding this phenomenon offers more than a quirky food fact—it reveals how deeply our genes influence everyday sensory experiences.

The Soapy Taste: A Genetic Quirk

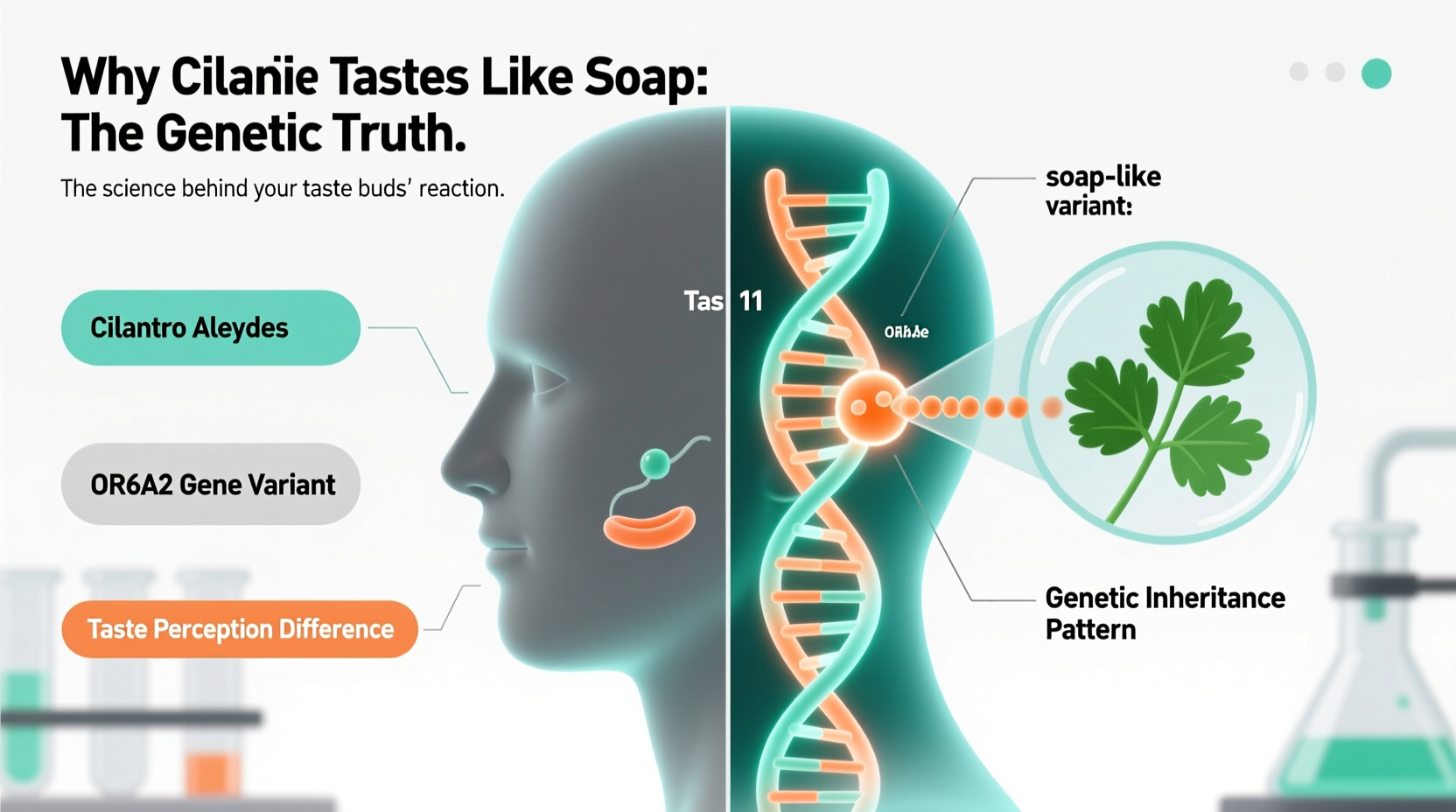

The aversion to cilantro isn't imagined. Scientific studies confirm that certain individuals experience a distinctly unpleasant, soapy flavor when consuming the herb. This reaction is primarily linked to variations in a cluster of genes responsible for detecting specific odor molecules—particularly aldehyde compounds.

Aldehydes are organic molecules found in both cilantro and common household products like soap and lotions. In cilantro, these compounds contribute to its characteristic aroma. However, for those with a particular genetic variant, the brain interprets these aldehydes as smelling and tasting like soap rather than fresh herbs.

A 2012 study published in the journal Flavour analyzed data from over 30,000 participants and identified a strong correlation between the presence of the OR6A2 gene and cilantro dislike. This gene codes for an olfactory receptor highly sensitive to aldehyde chemicals. Individuals who carry certain variants of OR6A2 are significantly more likely to describe cilantro as \"soapy,\" \"rancid,\" or \"chemical-like.\"

“Your nose isn’t lying. If cilantro tastes like soap, you’re genetically wired to detect specific compounds that most people barely notice.” — Dr. Charles Spence, Sensory Scientist, University of Oxford

How Genetics Shape Flavor Perception

Taste is not solely a function of the tongue. Up to 80% of what we perceive as flavor comes from smell. When we chew cilantro, volatile compounds travel through the back of the throat to the nasal cavity, where olfactory receptors interpret them. The OR6A2 receptor, when active, binds strongly to aldehyde molecules abundant in coriander leaves—the plant we call cilantro.

Interestingly, aldehydes were once widely used in perfumes and cleaning products before being phased out in favor of more pleasant scents. Their presence in soaps may explain why the cilantro-soap association feels so visceral to those affected. To them, eating cilantro is akin to chewing on a bar of old-fashioned soap.

Not everyone has this sensitivity. Genetic variation means that while roughly **4–14% of the global population** finds cilantro repulsive, others perceive only a mild, lemony freshness. Some people even report no distinct taste at all. This variation follows population trends: cilantro aversion is more common among people of European descent (up to 17%) and less prevalent in regions where cilantro is a staple, such as Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America (often under 3%).

Population Patterns and Evolutionary Clues

The distribution of cilantro aversion across populations suggests more than random mutation—it may reflect dietary adaptation. In cultures where cilantro has been used for thousands of years, natural selection may have favored individuals who tolerated or enjoyed its flavor, making the soapy perception less common.

Conversely, in regions where cilantro was historically absent, there was no evolutionary pressure to develop a preference. The persistence of the OR6A2 variant in these populations indicates that disliking cilantro carries no survival disadvantage—it's simply a neutral trait, like earwax type or bitter vegetable sensitivity.

Interestingly, cilantro contains natural antimicrobial properties, which may have made it valuable in warm climates where food spoilage was a greater risk. Regular consumption could have led to increased exposure and even acquired tolerance over time. This may partly explain why lifelong cilantro users rarely report the soapy taste, regardless of genetics.

Can You Train Yourself to Like Cilantro?

Genetics aren’t destiny. While your DNA sets the baseline for flavor sensitivity, experience and context play powerful roles in shaping taste preferences. Many people who initially hated cilantro grow to enjoy it through repeated exposure, especially when paired with complementary flavors.

This process, known as sensory adaptation, works by gradually reducing the brain’s negative response to a stimulus. Over time, the association between cilantro and “soap” can weaken, particularly if the herb is introduced in appealing dishes—like a well-balanced guacamole or a fragrant Thai curry.

Chefs and food scientists recommend these strategies for overcoming cilantro aversion:

- Start small: Use finely chopped cilantro sparingly in familiar recipes.

- Cook it: Sautéing, boiling, or roasting cilantro reduces volatile aldehydes.

- Pair wisely: Combine with fats (like avocado or yogurt) or acidic ingredients (lime juice, vinegar) to mellow the flavor.

- Try young leaves: Baby cilantro is often milder than mature leaves.

- Substitute strategically: Use parsley, celery leaves, or culantro (a related but stronger herb) as alternatives.

“I used to spit out any dish with cilantro. After moving to Mexico and eating it daily in tacos, I now crave it. My taste buds didn’t change—my brain did.” — Maria T., home cook and food blogger

Checklist: How to Navigate Cilantro Based on Your Genetics

Whether you love it or loathe it, here’s how to make informed choices about cilantro use:

- Take a genetic test (e.g., 23andMe) to check for OR6A2 variants.

- If sensitive, limit raw cilantro or use it as a garnish rather than a main ingredient.

- Experiment with cooking methods to reduce soapy notes.

- Communicate preferences when dining out or sharing meals.

- Don’t force yourself—there are plenty of flavorful herb alternatives.

- Educate others that your aversion is biological, not personal.

Do’s and Don’ts When Dealing with Cilantro Sensitivity

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Use cooked cilantro to reduce aldehyde levels | Assume everyone tastes cilantro the same way |

| Offer substitutions like flat-leaf parsley | Mock someone for disliking cilantro |

| Store fresh cilantro in water like herbs | Use large amounts of raw cilantro in shared dishes without warning |

| Blend into sauces or salsas for milder flavor | Believe that cilantro haters “just need to get used to it” |

| Respect individual taste differences | Disregard cultural preferences in group settings |

Expert Insight: The Science Behind Smell and Taste

Dr. Danielle Reed, a leading researcher at the Monell Chemical Senses Center, has spent decades studying genetic influences on taste. Her work highlights that flavor perception is not universal.

“We used to think taste was subjective, but now we know it’s biochemical. Genes like OR6A2 act like tuning forks—they make some people exquisitely sensitive to certain smells that others can’t detect. That’s not being fussy. That’s biology.” — Dr. Danielle Reed, PhD, Geneticist, Monell Center

Her research underscores that calling cilantro “soapy” is not hyperbole—it’s a literal description of what certain individuals smell and taste. The brain doesn’t distinguish between aldehydes in soap and those in cilantro; it responds to the chemical signature.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is cilantro really soapy, or are people exaggerating?

No exaggeration. The soapy taste comes from aldehyde compounds present in both cilantro and some soaps. People with the OR6A2 gene variant detect these compounds more intensely, making the comparison biologically accurate.

Can a blood test tell me if I’ll hate cilantro?

Not directly, but direct-to-consumer genetic tests like 23andMe analyze the OR6A2 gene and can indicate whether you carry the variant associated with cilantro aversion. Look for rs72921001 in your raw data.

Why do some people love cilantro while others hate it?

Differences stem from genetics, early dietary exposure, and cultural familiarity. Those with the sensitive gene variant are more likely to dislike it, but repeated positive experiences can override initial aversion.

Conclusion: Embracing Biological Diversity in Taste

The cilantro debate is more than a culinary quirk—it’s a window into human diversity. Our genes shape not just appearance and health, but also something as everyday as flavor. Recognizing that taste is influenced by biology fosters empathy in kitchens, restaurants, and homes.

Whether you sprinkle cilantro generously or remove it from every dish, your preference is valid. The key is understanding that no single palate defines “correct” taste. As science continues to unravel the links between DNA and diet, we gain deeper respect for the complex, individualized nature of eating.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?