Sleep talking, or somniloquy, is one of the most common yet least understood sleep behaviors. It affects people of all ages and can range from mumbled phrases to full conversations. While generally harmless, frequent or intense sleep talking may signal underlying conditions or stressors. Understanding the causes and frequency of this phenomenon helps demystify the experience for both individuals and their bed partners.

Unlike other parasomnias such as sleepwalking or night terrors, sleep talking doesn’t typically disrupt sleep architecture. However, it can be a window into deeper emotional or neurological processes. This article explores the science behind sleep talking, identifies key triggers, examines how often it occurs across different age groups, and offers practical advice for managing it when necessary.

The Science Behind Sleep Talking

Sleep talking occurs during any stage of the sleep cycle—both REM (rapid eye movement) and non-REM sleep—but manifests differently depending on the phase. During non-REM sleep, particularly stages 3 and 4 (deep sleep), speech tends to be fragmented, low-volume, and often nonsensical. These utterances are believed to stem from partial arousals, where parts of the brain briefly activate while others remain asleep.

In contrast, during REM sleep—the stage associated with vivid dreaming—speech may be more coherent, emotional, and contextually relevant to dream content. This is because the brain is highly active during REM, simulating waking thought patterns. However, motor inhibition normally prevents physical movement, including speaking. In sleep talkers, this inhibition appears incomplete or inconsistent.

Neurologically, sleep talking involves transient activation of the speech centers in the brain, primarily Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area, without full consciousness. Functional MRI studies suggest that these regions show brief bursts of activity during parasomnia episodes, even when the rest of the cortex remains in a sleep state.

“Sleep talking isn’t just random noise—it reflects real cognitive processing happening beneath the surface of unconsciousness.” — Dr. Lena Patel, Sleep Neurologist at Boston Sleep Institute

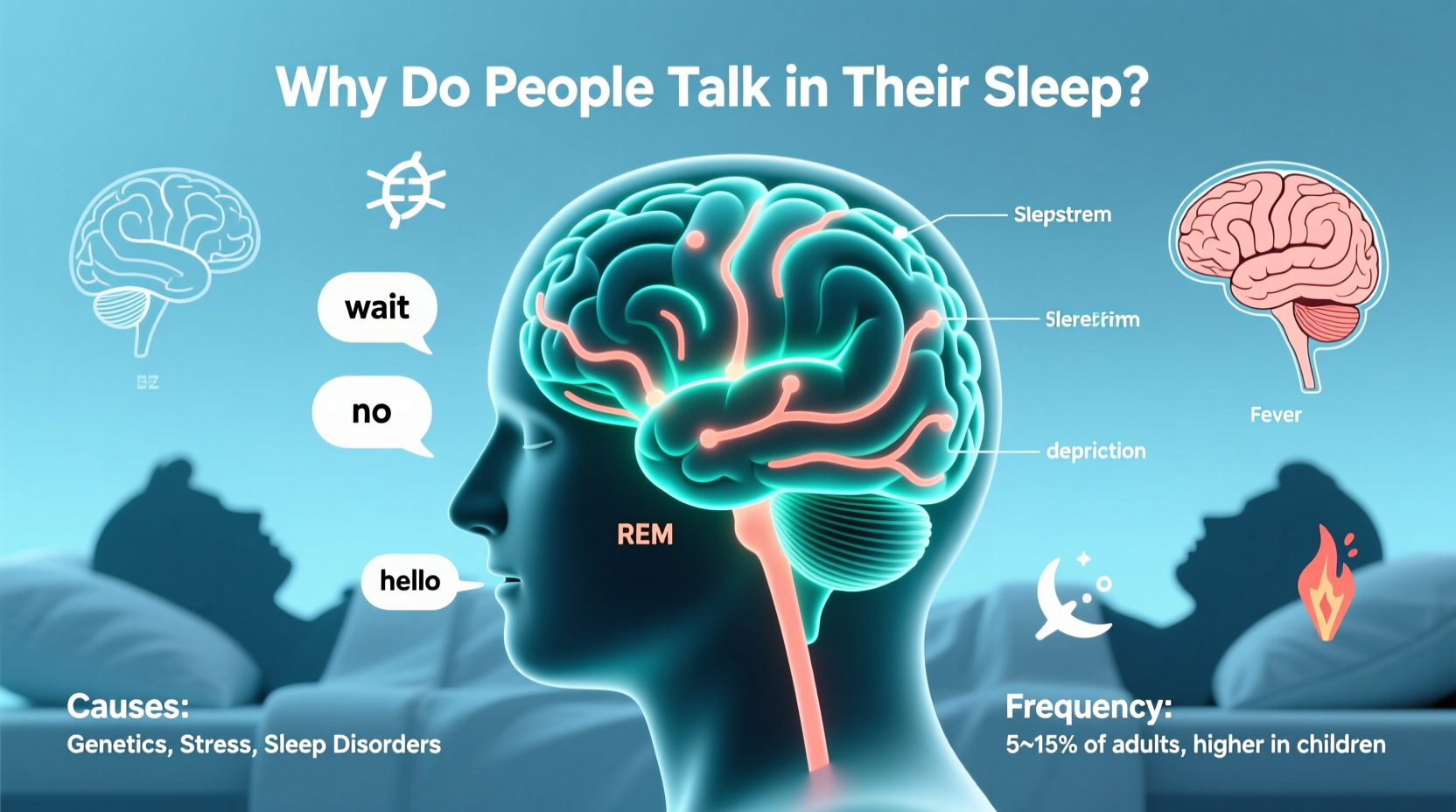

Common Causes of Sleep Talking

Somniloquy rarely has a single cause. Instead, it results from a combination of genetic, physiological, and environmental factors. Below are the most frequently identified contributors:

- Genetics: Studies show that sleep talking runs in families. If one or both parents talk in their sleep, their children are significantly more likely to do so.

- Stress and Anxiety: Elevated cortisol levels due to chronic stress can disrupt normal sleep cycles, increasing the likelihood of parasomnias.

- Fever or Illness: Especially in children, elevated body temperature can trigger temporary sleep talking episodes.

- Sleep Deprivation: Lack of consistent, quality sleep destabilizes brain function during transitions between sleep stages.

- Alcohol and Substance Use: Alcohol suppresses REM sleep early in the night, leading to REM rebound later—a period often accompanied by increased dream intensity and vocalizations.

- Other Sleep Disorders: Conditions like obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, and narcolepsy are frequently comorbid with sleep talking.

- Medications: Certain antidepressants, sedatives, and antipsychotics may alter neurotransmitter balance and promote parasomnias.

Frequency Across Age Groups

Sleep talking is surprisingly common but varies widely in frequency and intensity across life stages. A large-scale study published in *JAMA Neurology* found that nearly 50% of children aged 3–10 experience occasional sleep talking, compared to about 5% of adults over 25. However, lifetime prevalence suggests up to 66% of people report at least one episode in their lives.

| Age Group | Estimated Prevalence | Typical Frequency | Common Triggers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children (3–10) | 45–50% | Weekly or monthly | Fever, nightmares, developmental changes |

| Adolescents (11–17) | 20–25% | Occasional | Stress, irregular sleep schedules |

| Adults (18–64) | 5–10% | Monthly or less | Alcohol, anxiety, sleep apnea |

| Seniors (65+) | 3–5% | Rare | Neurodegenerative conditions, medications |

The decline in frequency with age correlates with brain maturation and stabilization of sleep architecture. Children’s brains are still developing neural pathways related to sleep regulation, making them more prone to partial arousals. As myelination and inhibitory control improve, parasomnias naturally decrease.

When Sleep Talking Signals a Larger Issue

While isolated incidents are usually benign, persistent or disruptive sleep talking may indicate an underlying health concern. Key red flags include:

- Episodes occurring multiple times per week

- Loud, aggressive, or emotionally charged speech

- Associated physical movements (e.g., sitting up, thrashing)

- Daytime fatigue despite adequate sleep duration

- Reports of violent or disturbing dream content

In such cases, a formal sleep evaluation—such as a polysomnography (sleep study)—can help identify coexisting disorders. For example, REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), which allows people to physically act out dreams, often begins with vocalizations before progressing to movement. RBD is linked to neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s, making early detection crucial.

Similarly, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) can cause micro-arousals that trigger sleep talking. The brain partially wakes to resume breathing, sometimes producing verbal responses. Treating OSA with CPAP therapy often reduces or eliminates parasomnias.

Mini Case Study: Identifying Underlying Sleep Apnea

Mark, a 42-year-old accountant, began sleep talking intensely six months after a stressful project at work. His wife reported nightly muttering, occasional shouting, and frequent pauses in breathing. Initially dismissed as stress-related, symptoms worsened over time. After a sleep study, Mark was diagnosed with moderate OSA. Upon starting CPAP therapy, his sleep talking ceased within three weeks, and daytime alertness improved dramatically.

This case illustrates how sleep talking can serve as an early warning sign. Without attention, Mark might have continued risking long-term cardiovascular strain due to untreated apnea.

Managing and Reducing Sleep Talking

For most people, no treatment is needed. But if sleep talking causes distress, embarrassment, or relationship strain, several strategies can help reduce frequency:

- Maintain a Consistent Sleep Schedule: Going to bed and waking at the same time every day stabilizes circadian rhythms and reduces sleep fragmentation.

- Limit Alcohol and Caffeine: Avoid both at least four hours before bedtime. Alcohol disrupts REM regulation; caffeine delays sleep onset.

- Practice Stress Reduction Techniques: Mindfulness meditation, deep breathing, or journaling before bed can lower nighttime arousal.

- Create a Relaxing Bedtime Routine: Dim lights, avoid screens, and engage in calming activities like reading or gentle stretching.

- Optimize Sleep Environment: Ensure the bedroom is cool, quiet, and dark. Consider white noise machines if external sounds trigger arousal.

- Treat Coexisting Sleep Disorders: If snoring, gasping, or excessive daytime sleepiness occur, consult a sleep specialist.

Checklist: Steps to Reduce Sleep Talking

- ✅ Go to bed and wake up at the same time daily

- ✅ Avoid alcohol within 4 hours of bedtime

- ✅ Limit screen exposure 1 hour before sleep

- ✅ Practice relaxation techniques nightly

- ✅ Keep bedroom temperature between 60–67°F (15–19°C)

- ✅ Address loud snoring or breathing interruptions with a doctor

- ✅ Keep a sleep diary for at least two weeks

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you control what you say while sleep talking?

No. People who talk in their sleep are not conscious and cannot regulate their speech. Statements made during episodes are not intentional and often lack logical coherence. They should not be taken as confessions or reflections of true feelings.

Is sleep talking hereditary?

Yes. Research shows a strong familial link. One study found that individuals with a first-degree relative who sleep talks are five times more likely to exhibit the behavior themselves. This suggests a genetic predisposition, possibly tied to shared brainwave patterns or sleep regulation mechanisms.

Should I wake someone who is sleep talking?

Generally, no. Waking a sleep talker can cause confusion or disorientation, especially if they’re in deep sleep. Unless the person is in danger (e.g., attempting to leave the bed), it’s better to let the episode pass naturally. Gently guiding them back to lying down is safer than full awakening.

Conclusion and Call to Action

Sleep talking is far more common—and complex—than many realize. While usually harmless, it offers insight into the dynamic interplay between brain activity, emotional health, and sleep quality. Recognizing the triggers and knowing when to seek help empowers individuals to protect their rest and overall well-being.

If you or a loved one experiences frequent or disruptive sleep talking, don’t dismiss it as mere habit. Small lifestyle adjustments can yield significant improvements. And when in doubt, consulting a sleep specialist could uncover treatable conditions that affect more than just nighttime chatter.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4

Comments

No comments yet. Why don't you start the discussion?